Today, everyone knows about dinosaurs, but 200 years ago, people were unaware that dinosaurs existed in prehistoric times, let alone that they dominated the Earth for 180 million years during the Mesozoic Era, 245 million years ago. Interestingly, the discoverer of dinosaurs was not a paleontologist, but a country doctor named Kiddane Mantell from a small town in Sussex, in southeast England. He had a deep interest in geology and paleontology, and in his spare time, he often took his wife Mary to collect fossils outside the town, a pursuit he thoroughly enjoyed.

One spring day in 1822, he and his wife went to make house calls in the most fashionable carriage of the time. While Mantel was seeing patients at their homes, Mary was taking a walk along a country road—one of the most fruitful walks in the history of science. A pile of gravel intended for road repairs immediately caught Mary's attention. She searched intently among the gravel, and suddenly spotted a glittering stone. She picked it up out of curiosity, completely unaware of the significance of her action.

This unusual rock contained a huge fossilized tooth. Mantel was overjoyed when he found it. He learned that the roadside gravel had been transported from a quarry, so he rushed there and found several more fossilized teeth. He was certain that the tooth belonged to an ancient animal because the quarry was located on the Cretaceous floor.

But what kind of ancient animal was it? Mantel consulted with the leading paleontologists of the time, the Frenchman Joël Cuvier (1769-1832) and British paleontologists, whose answer was: "Although we do not know what kind of animal it is, it seems to be the tooth of a mammal."

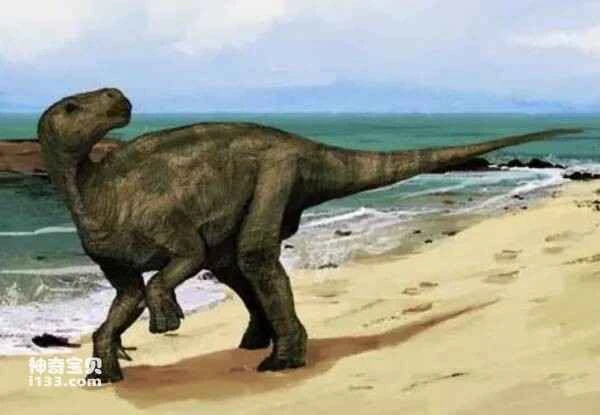

Dissatisfied with this answer, Mantel went to the renowned H.H. Renault Paleontological Museum in London and, with permission, took the tooth fossil into the museum's specimen storage room. Despite repeated searching, Mantel couldn't find a tooth similar to the one he was looking for. Resting in the museum, Mantel looked dejected. At this time, a young man struck up a conversation with him. When the young man learned that Mantel had come to the museum to identify teeth, he told him, "These are iguana teeth. Because I've been studying iguanas in South America, I'm sure I'm not mistaken." So, Mantel returned to the storage room to examine iguana teeth. The result was exactly as the young man had said: the fossil in his hand was very similar to an iguana tooth, only much larger. Based on this, Mantel deduced that the tooth fossil belonged to some unknown, giant herbivorous reptile from ancient times. He named this animal Iguanosaurus, meaning an animal with teeth like a large lizard, now translated into Chinese as "Iguanosaurus."

Decades later, the renowned British biologist Irwin further concluded that these fossil reptiles should not be classified with modern reptiles. They were neither ancient crocodiles nor ancient lizards, but rather unique reptiles that had long since become extinct on Earth—dinosaurs.

Since then, Mantel has given up his job as a doctor and devoted himself to searching for dinosaur fossils. He has kept the collected dinosaur bones in his home, which has become a veritable hospital and museum.

The year before his death, in 1851, London hosted the first World's Fair, which exhibited fossilized iguanaosaur teeth unearthed by Mantell, along with models of Iguanodon and Herierasaurus reconstructed from these teeth, which were very popular. For Mantell in his later years, nothing could have brought him greater joy.

A series of discoveries

In 1878, miners discovered a graveyard of Iguanodon at a depth of approximately 300 meters in the Bernese Salzburg coal mine in Belgium, reigniting public interest in dinosaurs. Initially, only incomplete dinosaur fossils were found, but soon 39 complete skeletons were discovered. It turned out that the area was a swamp, and the Iguanodon that had fallen from the mountains into the swamp became their graveyard. Ten of these Iguanodon fossils are now on display at the Royal Natural History Museum in Brussels, Belgium. In a glass-enclosed room, the ten Iguanodon skeletons, reaching to the ceiling, form a beautiful sight.

Meanwhile, a dinosaur craze swept across the United States. Funded by the Morgan financial group and steel magnates, numerous dinosaur and other fossils were unearthed, now displayed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Pittsburgh Museum of Natural History. Among these discovered dinosaur fossils, the largest was a herbivorous dinosaur—the Apatosaurus, approximately 20 meters long and weighing around 25 tons. Other discoveries were also interesting. In a cave inhabited by ancient Native Americans in Wyoming, there were large pillars, one of which was unusual. The Native Americans believed it to be a spirit and often communicated with it. After investigation, staff at the American Museum of Natural History in New York discovered that it was actually a fossil of an Apatosaurus foot, marking the beginning of Apatosaurus research.

Furthermore, footprints of a pterosaur, a carnivorous dinosaur that chased an Apatosaurus, were discovered in Glenrose, southwest of Dallas, Texas. At that time, the area appeared to be wetlands. The fossilized footprint was moved intact to the American Museum of Natural History in New York and used as a display base.

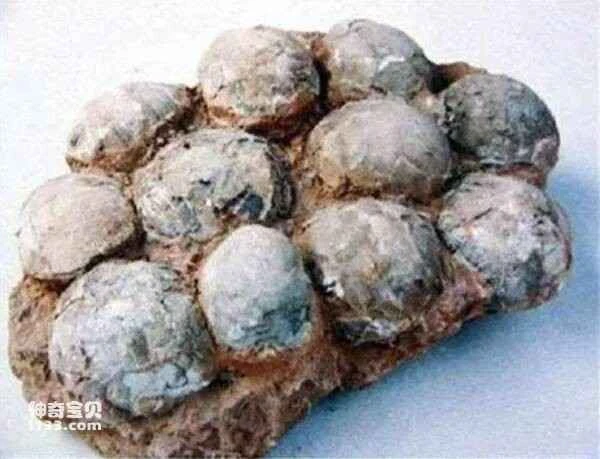

Furthermore, Henry Osborne, the fourth curator of the New York Museum of Natural History, discovered dinosaur eggs, providing a new field of research for later generations. Inspired by the discovery of Peking Man in 1922, he also wanted to search for fossils in Asia, so he formed an expedition led by Louis Andrews and including Osborne and others to explore the Mongolian desert. After a period of exploration, before returning for winter, Osborne suddenly discovered a rock that looked very much like a dinosaur egg at the foot of a cliff. However, because the group had no interest in lingering, they hastily left.

The following spring, Osborne returned to the site. He first went to the Gobi Desert. Although the terrain made it impossible to pinpoint the exact location where the eggs had been found the previous year, he determined the general area and began his search. Several days passed without progress. Then, one day after lunch, they unexpectedly discovered dinosaur egg fossils. In the days that followed, they found a total of 25 dinosaur egg fossils arranged in a spiral, suggesting that the dinosaur mother had laid them while walking. Later identification confirmed they were eggs of a Protoceratops from the Late Cretaceous period (approximately 97-65 million years ago).

It's incredible that these eggs have been preserved intact for tens of millions of years. We know that in Mongolia, summers are relatively warm but winters are cold. Could this be the reason the eggs didn't crack and froze?

Dinosaur fossils tell the story of continental drift

During the Early Triassic period (approximately 245-241 million years ago), mammals and reptiles included the Lystrosaurus, which was about 1 meter long. Its fossils were discovered in Antarctica starting in the late 1960s and attracted considerable attention. According to the continental drift theory proposed by German meteorologist Alfred Wegener around 1910, approximately 150 million years ago, the continents on Earth were originally clustered together, forming Pangaea, and subsequently drifted to their current positions.

Low temperatures led to extinction

Around 65 million years ago, during the transition from the Mesozoic to the Cenozoic era, the disappearance of dinosaurs and their relatives paved the way for the final emergence of mammals and humans. Various hypotheses remain regarding the extinction of dinosaurs, with no definitive conclusion. One is the "gradual extinction theory," and the other is the "aggravated extinction theory." Regardless of the theory, the extinction of dinosaurs was certainly related to environmental changes. Representative contributing factors to the "gradual extinction theory" and the "aggravated extinction theory" are the "declining temperature theory" and the "meteorite impact theory," respectively.

The Mesozoic Era saw a rare period of warmth with almost no ice cover, during which global temperatures were 8-10°C higher than they are today. However, from the end of the Mesozoic Era to the beginning of the Cenozoic Era, vast glaciers cooled ocean currents and atmospheric circulation, causing a drop in global temperatures. Glaciers locked in water, lowering sea levels and destroying previously abundant vegetation, making it unsuitable for the survival needs of dinosaurs and leading to their extinction. Earth has experienced several ice ages in its history, but the timing and evidence for ice ages before the Sinian Period are currently unclear. More recently, the fifth ice age occurred approximately 2 million years ago, and the sixth ice age occurred approximately 60,000 to 10,000 years ago. The lowest temperatures during this ice age were recorded around 18,000 years ago, when temperatures were 5-10°C lower than they are today.

In the past, dinosaurs were cold-blooded animals like snakes. As winter approached and temperatures dropped, snake activity decreased, making their extinction understandable. However, recent anatomical evidence from dinosaur fossils reveals the presence of Haversian canals in dinosaur skeletons. These canals, located in the center of each long bone unit, contain abundant blood vessels and a complex system of tubules responsible for transporting substances essential for bone metabolism. The dense Haversian canals indicate ample blood supply, reflecting a high metabolic rate, a characteristic of warm-blooded animals. Based on this, scientists speculate that dinosaurs were likely not cold-blooded and could stably control their body temperature. This structure undermines the argument that a drop in temperature caused dinosaur extinction.

Of course, it's insufficient to conclude that dinosaurs were warm-blooded based solely on this, as their metabolism was so slow that they couldn't possibly maintain a comfortable body temperature. Further research shows that Haversian canals are not unique to warm-blooded animals; they are formed due to increased metabolism caused by vigorous activity. The presence of Haversian canals in dinosaurs simply indicates that they were very active and able to actively increase their metabolic rate.

In response, American paleontologists have proposed a new hypothesis called "thermal inertia." Thermal inertia is the body's ability to conduct and store heat, which can come from metabolism or the animal's movement. It differs from the way warm-blooded animals maintain their body temperature, but they share a similar principle. Thermal inertia involves minimizing heat loss through a large body size, thus maintaining a higher body temperature. Large animals typically possess this mechanism because their surface area to volume ratio is lower than that of smaller animals. For example, an elephant loses heat much more slowly than a mouse.

This clearly demonstrates that, at least in that era, dinosaurs achieved ecologically successful adaptation through their own methods. Moreover, warm-blooded dinosaurs had a greater survival advantage: they didn't need to expend large amounts of energy to generate metabolic heat to maintain their body temperature. In other words, if we, like these giant animals, used thermal inertia to maintain our body temperature, we could save a significant amount of money on food. Clearly, the gradual extinction theory cannot explain why dinosaurs, with their survival advantages, went extinct.

A giant meteorite struck Earth

Now we turn to the meteorite impact theory, which represents the extinction hypothesis. In 1980, Luis Alvarez of the University of California, Berkeley, pointed out in his paper that the iridium content in the boundary layers between Mesozoic and Cenozoic strata in Italy, Denmark, New Zealand, and other places was 100 times higher than that in the layers above and below. Iridium belongs to the platinum group elements and is generally not found in the Earth's crust. The reason why the iridium content in the boundary layers is high is mainly due to the impact of a huge meteorite on Earth. The evidence is that the iridium isotope ratio in the boundary layers is exactly the same as the iridium isotope ratio in the meteorite. Later, boundary layers with high iridium content were found in various parts of the world. It is now known that based on the amount of iridium contained in a unit mass of meteorite, the diameter of the meteorite that impacted Earth can be estimated to be about 10 kilometers, and it is believed that it was the huge meteorite impact that caused the extinction of dinosaurs and other ancient creatures.

Meteorites typically impact Earth at speeds of 20 kilometers per second. A meteorite 10 kilometers in diameter impacting Earth at this speed could create a crater approximately 100 kilometers in diameter and 30 kilometers deep. The Chiclarubo crater on the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico is the most compelling evidence of this. At the time of that violent impact, global forest fires raged, resulting in dust particles roughly twice the mass of the meteorite being ejected. Microparticles smaller than 1 micrometer in diameter remained trapped in the atmosphere for an extended period, forming a dense, opaque barrier. The entire Earth was plunged into darkness for weeks or even months afterward, and even the oceans almost completely "satirized." As a result, terrestrial plants withered, and marine plankton were unable to photosynthesize, disrupting the primary food chain and leading to the extinction of the dinosaurs that inhabited the globe.

However, some experts believe that this "cosmic killer theory" has many flaws. Based on their existing knowledge, even when faced with unexpected extreme cold, dinosaurs living in Alaska remained remarkably well-preserved. Therefore, some experts believe that the more significant reason for the successive extinctions of dinosaurs worldwide was likely the abnormal changes in air currents and ocean currents caused by sudden climate change.

Of course, there's also the so-called "disease threat" theory regarding the extinction of dinosaurs. Scientists have discovered that a dinosaur called Allosaurus, similar to Tyrannosaurus Rex, has unique damage marks on its skeletal fossils, left by viral infections. All animals are susceptible to the threat of pathogens, and dinosaurs were clearly no exception.

Dinosaurs are extinct, and although the reasons are still inconclusive, we believe that a clear explanation will eventually be given so that dinosaurs can "die with a clear understanding."