Imagine you are a researcher who has conducted a brilliant experiment and successfully completed it, utilizing all your scientific expertise. Many years later, your phone rings with congratulations from your colleagues, for you have just won the Nobel Prize. You fly to Stockholm, Sweden, step onto the stage, and the King awaits you…

People often imagine using past memories to construct a picture of the future, a concept that may never actually occur. Researchers call this mental time travel (MTT), a term coined in the 1990s by psychologists Thomas Suddendorf of the University of Queensland, Australia, and Michael Corballis of the University of Auckland, New Zealand. They argue that MTT, including conscious thought, is unique to humans. They have established stringent criteria for demonstrating this behavior in animals and insist that it has not been observed even in the most intelligent non-human species.

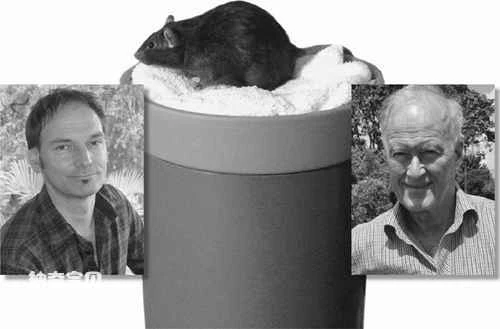

Michael Corballis (right) believes that mice can travel through time psychologically, while Thomas Suddendorf (left) disagrees.

Following this, hundreds of other researchers conducted experiments attempting to demonstrate whether animals could also perform MTT—a crucial step in planning the future. Now, inspired by new research on the mouse brain, Corballis has changed his thinking and understanding. Last month, the two, still on friendly terms, engaged in an academic debate in the journal *Trends in Cognitive Science*. Corballis claims that the research shows mice not only repeat maze routes they've run before, but also mentally explore routes they've never taken before—a form of MTT. Suddendorf, however, maintains his original view.

Scientists conducting this type of research say that some non-human species must exhibit MTT behavior, although there is no way to explain the consciousness of these animals. They cite examples such as birds storing food for later use, and a chimpanzee named Santino hoarding stones to throw at zoo visitors later.

Suddendorf maintains that these phenomena are not evidence of MTT. He states that animals do possess some MTT components, including the ability to visualize external physical space in the brain and understand the world around them. "However, MTT includes more than that; it allows us to flexibly imagine any scenario and future plot, and prepare for unforeseen events."

Corballis did not suggest that animals possess the same imaginative abilities as humans. However, he said that the MTT behavioral test he and Suddendorf designed—which involves using new questions and single experiments that animals cannot learn through learning—may be overly demanding. Corballis stated that the new mouse research provides “deeper information” about what animals might be capable of.

Recent research has recorded neural impulses in the hippocampus of mice while they run a maze. Corballis states that the hippocampus is a key component of memory storage in humans and animals, "and is crucial for human MTT (memory transference)." The groundbreaking experiment, led by neuroscientist A. David Redish of the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, was reported in 2007.

A paper published last year in the journal *Science* supported this finding. The paper noted that when mice learn a maze, their hippocampal neurons repeat previous routes and possible future routes, even when they are resting outside the maze. A paper published last month in *Science* showed that mice use place cells to map the 3D space they have traversed.

Corballis believes that a growing body of research suggests that "MTT has ancient origins," though he also acknowledges that human MTT behavior is far more complex. Redish states that despite "significant differences" between mice and humans, he "fully believes that MTT behavior exists in animals as well."

Suddendorf countered that mice only possess a part of the complete MTT (Multi-Track Theory). For example, they lack subjective consciousness and so-called recursive thinking: the ability to combine images and experiences to construct infinite future scenarios (such as winning a Nobel Prize or traveling to outer space).

Some animal behavior experts claim that non-human MTT (Mean Transmission Tolerance) does exist, though their reasoning differs from Corballis's. Mathias Osvath, a primatologist at Lund University in Sweden, stated that studies on chimpanzees and birds storing food for later use are "more compelling" than findings from mouse studies. He studied Santino, a chimpanzee at Furuvik Zoo, who throws stones. He says these studies prove the existence of MTT. He believes it's unnecessary to use conscious or fictional ideas to prove MTT behavior in animals.

Both sides of the debate have their own arguments, which pave the way for future research on non-human MTT. Corballis favors neurophysiological studies like those on the mouse hippocampus, while Suddendorf argues that if animals do exhibit MTT behavior, it should be verified through "more rigorous" behavioral tests. Both he and Corballis agree on a key point: only through the evolution of language can animals begin to share their MTT stories and truly realize those imagined scenarios.