Located 20 degrees east longitude, south of the Arctic Circle, a group of desolate islands drift forlornly in the eastern Greenland Sea, huddled in the biting winds. This is the Svalbard archipelago, a place that would normally go unnoticed.

On August 3, 1960, an expedition team of geologists and paleontologists from different countries discovered 13 ancient animal footprints on a Cretaceous sandstone cliff in the Svalbard archipelago. Each footprint was 60-75 centimeters long and clearly showed three toes. Within a distance of 13.5 meters, seven footprints were arranged in a row, while the others were scattered in all directions.

Scholars almost unanimously concluded: "These are precious footprints left by Iguanodon, one of the most abundant dinosaurs on Earth 100 million years ago." Soon, the news spread like wildfire, reaching all corners of the world and becoming major news on radio stations and in newspapers.

As everyone knows, the Mesozoic Era was the world of dinosaurs. Within this vibrant dinosaur kingdom, Iguanodon was a member of the diverse ornithopods. They were generally around 10 meters long and about 5 meters tall; their bodies were bulky, with thick tails; their forelimbs had five fingers, ending without claws, resembling human hands; they typically walked on two legs, each with three toes. They leisurely foraged, drank, and roamed in dense forests, humid swamps, or lakeshores. The renowned Chinese paleontologist Professor Yang Zhongjian also discovered Iguanodon footprint fossils in Shenmu County, Shaanxi Province, my country in 1929.

Iguanodon fossils are among the earliest dinosaur fossils discovered by humans. The first dinosaur fossils collected by English country doctor Mantell in March 1822 from the rock strata inside a newly cut road in Sussex, southern England, were Iguanodon teeth and bone fossils.

Over the next 100 years, scientists gradually unveiled the history of Iguanodon, revealing few remaining secrets. However, these "close-up shots" of Iguanodon in the Svalbard archipelago caused a great stir. This is related to the unique geographical location of the Svalbard archipelago.

Among the fossil sites where dinosaur remains have been discovered in the past, the closest to the North Pole is at least 4,000 kilometers away, while the Svalbard archipelago is only 1,300 kilometers away. How can one not be astonished to push the northern boundary of the dinosaur distribution area so far north?

Scientists speculate that the Svalbard archipelago, which today appears to float like a few small boats on the vast ocean, must have been connected to the Eurasian continent during the Cretaceous period 100 million years ago. Otherwise, how could Iguanodon have had the ability to conquer 700-800 kilometers of sea surface and land on the Svalbard archipelago?

Like modern reptiles, dinosaurs were cold-blooded and unable to regulate their body temperature. Their body temperature varied with the ambient temperature. In very cold weather, they would quickly freeze to death, so they could only establish their habitat in tropical and subtropical climates. However, the Svalbard archipelago today is located in the Arctic region with an extremely cold climate. If this was also the case during the Cretaceous period, how did these Iguanodon dinosaurs survive?

Clearly, the Iguanodon was too large to hibernate underground like crocodiles, snakes, turtles, or lizards. So, was the Svalbard archipelago, where the Iguanodon footprints were discovered, also a perpetually hot region back then?

Many paleontologists and geologists believe that during the Cretaceous period, most of the Earth had a tropical climate, and these warm conditions were particularly suitable for the survival and reproduction of dinosaurs. At that time, from Australia and Africa to northern Eurasia, there were ideal habitats for dinosaurs. Even the North and South Poles of today were at best considered "cool" places at that time.

However, a warm climate alone is not enough. Iguanodon was a herbivorous dinosaur, requiring large amounts of plant matter daily to sustain its massive body. But plants cannot grow without sunlight, and the Svalbard archipelago, located near the Arctic Circle, experiences four months of complete darkness during winter. Could the Iguanodon withstand four months of starvation? Otherwise, where would it find food?

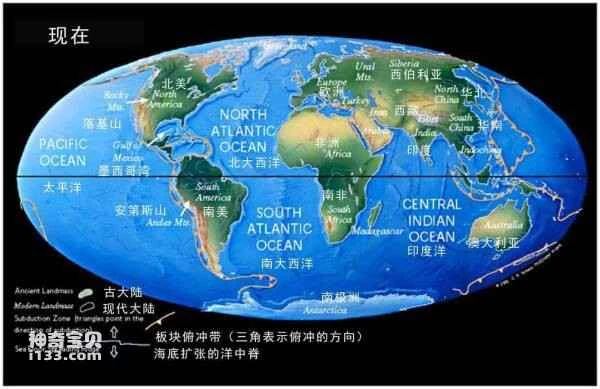

The Triassic supercontinent on Earth

This contradiction may be explained by the theory of continental drift.

During the Triassic period, the continents of today were all connected, forming a supercontinent called "Union." Later, Union broke apart into several landmasses, which drifted over a long period of time and eventually settled to their current locations.

During the Late Cretaceous period, 70 million years ago, the Svalbard archipelago was part of the northward-drifting Eurasia. In the time of the Iguanodon, the Svalbard archipelago was still located in a relatively southern region, where there was ample sunshine and vegetation that could grow year-round, providing the Iguanodon with abundant food.

Iguanodon life picture

Recently, another explanation has gained increasing attention in the scientific community: the "polar migration theory." Studies of the magnetism in rocks suggest that in past geological eras, the Earth's poles were not in their current positions. Some scientists believe that during the dinosaur era, the North Pole was located north of Siberia, while the Svalbard archipelago was only around 60 degrees north latitude, similar to the latitudes of Oslo and Stockholm today. This meant that its southern part still received ample sunlight, sustaining plant growth and providing a sufficient food source for Iguanodon.

The discovery of Iguanodon footprints in Svalbard is one of the most interesting and important events in the more than 100 years of dinosaur fossil discoveries. Its value extends far beyond the exploration of the Iguanodon species itself. It provides crucial clues for scientists to understand the Earth, its environment, and the lives of its inhabitants 100 million years ago.