Another theropod dinosaur found in the lower part of the Yixian Formation is the unexpected Beipiaoosaurus, whose discovery, as its species name suggests, was entirely accidental. In 1997, Mr. Li Yinxian of the Beipiao City Fossil Management Office donated a pile of relatively fragmented fossils to the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. At the time, no one expected that such a seemingly insignificant pile of fragmented fossils would "fly out" a "golden phoenix." After careful and meticulous research, Associate Researcher Xu Xing discovered that it was a new and important member of the Therizinosauridae superfamily.

Unexpected Beipiao Dragon

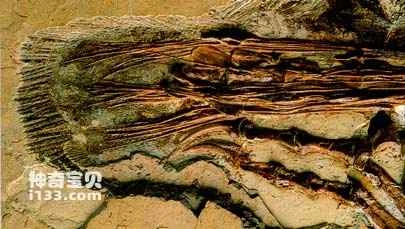

Due to the highly unusual morphology of therizinosaurs, paleontologists have long debated their systematic classification within the dinosaur family. The unexpected discovery of *Beipiaosaurus* suggests that therizinosaurs were a highly specialized group among carnivorous dinosaurs. Furthermore, *Beipiaosaurus* unexpectedly preserved filamentous skin derivatives similar to those found in *Sinosauropteryx*, indicating that such filamentous skin derivatives may have been present in many theropod dinosaur types, representing an early stage in the evolution of later bird feathers.

Millennium Sinosauropteryx

The discovery of the fifth dinosaur found in the lower part of the Yixian Formation—Sinornithosaurus millenniarum—was even more dramatic. In the summer of 1998, the Liaoning field team of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, excavated a holotype specimen of this dinosaur near the fossil site of *Sinornithosaurus* on the last day before their team's departure. *Sinornithosaurus millenniarum* belongs to the Dromaeosauridae family of theropoda. Dromaeosaurid dinosaurs hold special significance in the study of the origin of birds.

In the 1970s, Professor Ostrom of Yale University, an internationally renowned paleontologist, revived the hypothesis that birds originated from theropod dinosaurs by studying dromaeosaurid fossils discovered in the Early Cretaceous strata of North America. This hypothesis gained widespread acceptance in the paleontological community. However, due to the limitations of fossil materials, there were many misunderstandings in the past regarding the anatomical structure of dromaeosaurids. Consequently, this hypothesis was attacked by reactionaries in some aspects.

The discovery of *Sinornithosaurus* provides more reliable material for detailed studies of the anatomy of dromaeosaurids. Preliminary research shows that dromaeosaurids were morphologically very close to early birds, with their postcranial skeletons differing significantly from most dinosaurs and exhibiting many early bird characteristics. Their pectoral girdle (the bone connecting the forelimbs to the vertebrae) structure is almost identical to that of *Archaeopteryx*. Although *Sinornithosaurus* could not fly, its skeletal structure had already undergone a series of evolutionary adaptations for flight, and its skeletal system fully met the requirements for flapping its forelimbs, representing a typical pre-evolutionary pattern. *Sinornithosaurus* also developed filamentous skin derivatives, further demonstrating the widespread presence of this structure in non-avian theropod dinosaurs and providing important insights into the origin and evolution of feathers.

To date, several theropod dinosaurs discovered in the lower strata of the Yixian Formation in western Liaoning Province have skin derivatives resembling bird down or feathers. This is the first time such structures have been found in a group of organisms other than birds. Phylogenetic analysis and studies of the growth of these skin derivatives in these animals indicate that the filamentous skin derivatives found in therizinosaurs and compsognathus represent an early stage of feather evolution, likely marking the beginning of feather origin and subsequent evolution into more complex body feathers. In theropod dinosaurs, symmetrical feathers with vanes likely developed during the Maniraptorian evolutionary stage. Asymmetrical, vane-like "advanced" feathers, however, appeared only after the origin of birds, their function clearly serving to aid flight. Therefore, feathers are no longer a sufficient identifying characteristic of birds, as they existed before the emergence of birds. In the future, if we discover fossils of animals with feathers, we must carefully examine their skeletal morphology to determine whether they belong to birds or theropod dinosaurs.