In the early Eocene epoch of North America, 50 million years ago, a fox-sized herbivore emerged from the primitive hoofed ungulates. Known as Eohippus, it is not only the ancestor of the modern horse but also the earliest type of all perissodactyls closely related to horses. From then on, modern ungulates began to appear on the historical stage.

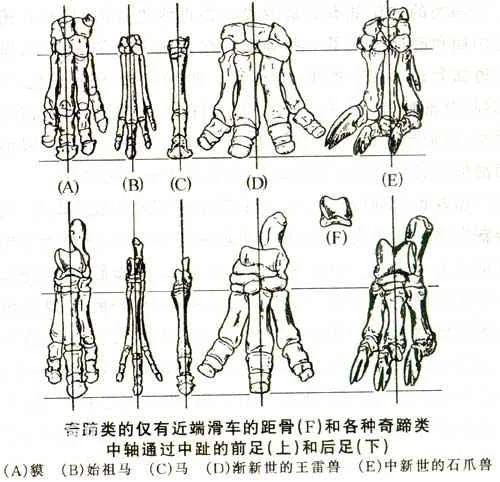

Foot bones of various odd-toed ungulates

Perissodactyls typically have an odd number of toes, with the middle toe passing through the central axis of the foot. The big toe (the inner toe) of both fore and hind feet, and the fifth toe of the hind foot, are degenerate and have disappeared; the fifth toe of the forefoot was retained in primitive types but has disappeared in advanced types. Therefore, perissodactyls often have only three functional toes on their fore and hind feet, compared to only one middle toe in advanced modern equines. In the ankle of perissodactyls, the proximal end of the talus (the end closer to the body) has a double-projected trochlear-shaped surface that articulates with the distal end of the tibia (the end farther from the body), while the distal end of the talus forms a flat surface where it meets the other bones of the ankle. The concentration of functional toes on only a few, or even just one, and the trochlear structure of the talus, enable perissodactyls to run much faster to escape dangerous predators—a significant progressive feature that distinguishes them from ankyloids. Furthermore, the femur of perissodactyls has a prominent projection on the lateral side of the shaft, called the third trochanter.

During evolution, perissodactyls gradually increased the crown of their teeth, and their premolars tended to become molars. This was an adaptation to their diet of fibrous hard grass and hay in arid grasslands.