Reptiles are the earliest amniotes to appear on Earth, evolving from labyrinthoids, a type of amphibian. This transition from amphibians to reptiles occurred during the Carboniferous period, marked by the production of amniotic eggs. Besides this crucial characteristic of amniotic egg production and the fact that reptile development does not require metamorphosis, reptiles also exhibit many skeletal structural features that differ from amphibians.

Reptile skulls are relatively high, unlike the typically flattened skulls of labyrinthine amphibians; the bones behind the parietal bone are sometimes smaller, sometimes displaced from the tectum to the occipital region, and sometimes even disappear completely. Most reptiles have only one occipital condyle.

The vertebrae of reptiles consist of a large lateral vertebral body and a smaller, wedge-shaped intervertebral body; in more advanced types, the intervertebral body is absent. Primitive reptiles had two sacral vertebrae, unlike amphibians which had one; in many advanced reptiles, the sacrum consists of several vertebrae, some types having as many as eight. The ilium also enlarges along with the sacrum. In primitive reptiles, the ribs are continuous and roughly similar from the head to the pelvis; however, in advanced reptiles, the ribs are typically divided into cervical ribs, thoracic ribs, and ventral ribs.

The earliest and most primitive reptiles discovered to date are the cupulaosaurs of the Early Permian. From this foundation, reptiles, due to their evolved reproductive advancements, were exceptionally adapted to the terrestrial environment of the time, and thus quickly diverged explosively in various evolutionary directions. During the Mesozoic Era, from the Early Triassic to the End of the Cretaceous, a diverse array of reptiles virtually dominated all terrestrial ecosystems on Earth; some groups even returned to aquatic life, becoming the dominant species; and another group took to the skies. Therefore, the Mesozoic Era can be considered the Age of Reptiles.

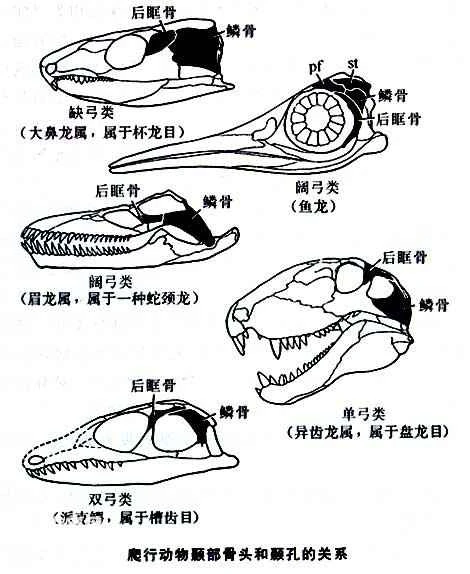

Based on the development of the temporal region of the skull, specifically the relationship between the development and changes of the temporal foramen, reptiles can be divided into four subclasses: the subclass Anomala, the subclass Monoarchala, the subclass Broad-archala, and the subclass Dinomala.

Temporal apertures of various reptiles

So, what is the temporal femur? Let's first examine the skulls of cuposaurs. The skulls of cuposaurs are similar to those of their labyrinthodontic ancestors, with a solid roof structure containing only the nostrils, eye sockets, and pineal foramen. Later, with the evolution of reptiles, additional openings typically appeared on the top of the skull behind the eye sockets; these are the temporal femurs. The temporal femur's function is to accommodate powerful jaw muscles; therefore, its presence, number, and location determine the animal's biting pattern, indirectly influencing many of its behaviors and physiological characteristics. Therefore, using the development and changes in the temporal femur as an important basis for the internal classification of reptiles is scientifically sound.

Some reptiles have only one temporal foramen on the roof of their skull behind the eye socket; others have one on the side of the skull. Still others have two temporal foramina, one on the top of the skull and the other on the side. The superior temporal foramen is bounded ventrally by the postorbital and squamous bones, while the lateral temporal foramen is bounded dorsally by the same bones. When both foramina coexist, they are separated by the postorbital and squamous bones. The four subclasses of reptiles are distinguished based on the presence or absence of temporal foramina and their variations. Building upon this, and using other characteristics, reptiles can be further subdivided into more detailed taxonomic ranks.