The reduction in the number of fingers or toes has occurred many times in the evolutionary history of tetrapods. The most famous example is the "Equus fossil sequence" (a series of equine fossils from primitive to advanced stages, revealing the gradual reduction of fingers/toes in equines). On August 24th, an international research team led by Professor Xu Xing of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, published their latest research findings in the journal *Current Biology*. They discovered two new dinosaurs in China: *Bannykus wulatensis* and *Xiyunykus pengi*. The discovery of these two dinosaurs enhances our understanding of the complex process of how alpharasaurids reduced and gradually lost their fingers. The fossil specimens of these two new dinosaurs were discovered and collected by a joint expedition led by Professor Xu Xing of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Professor James Clark of George Washington University, and Professor Tan Lin of the Longhao Institute of Geology and Paleontology, Inner Mongolia. Among them, the Western Clawed Dragon was discovered in the Junggar Basin of Xinjiang, China in 2005, and the Hemiclawed Dragon was discovered in the northwestern part of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China in 2009.

Figure 1. Reconstruction of Bannykus wulatensis (Image provided by Xu Xing, illustration by Shi Aijuan)

Alvarezsaurids are perhaps the most peculiar group of theropod dinosaurs. They possessed extremely short yet incredibly powerful forelimbs, each with only one specialized large claw, yet simultaneously had bird-like skulls and hind limbs. These unusual features have led to widespread debate regarding their phylogenetic position, biogeographical evolutionary history, and ecological niche. Early, less specialized alvarezsaurid fossils are key to resolving these controversies. However, until this discovery, the fossil record of alvarezsaurids had a gap of over 90 million years between the most primitive groups (such as *Hypodiopteryx nigra*, living in the Late Jurassic) and more advanced groups (such as *Xiacanthosaurus zhangi*, living in the Late Cretaceous), particularly in the Early Cretaceous, where there was no definitive fossil record worldwide.

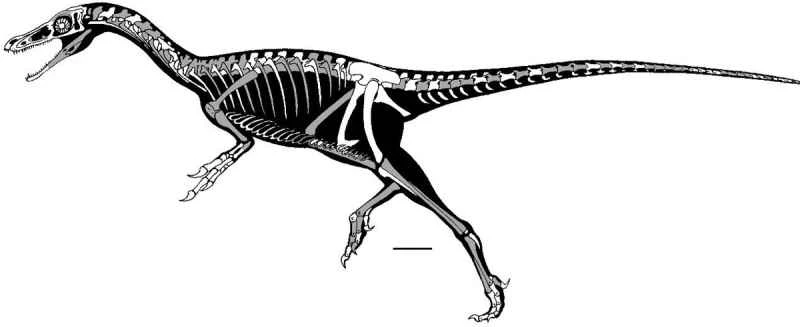

Figure 2. Skeletal line drawing of Xiyunykus pengi (provided by Xu Xing, illustrated by Shi Aijuan)

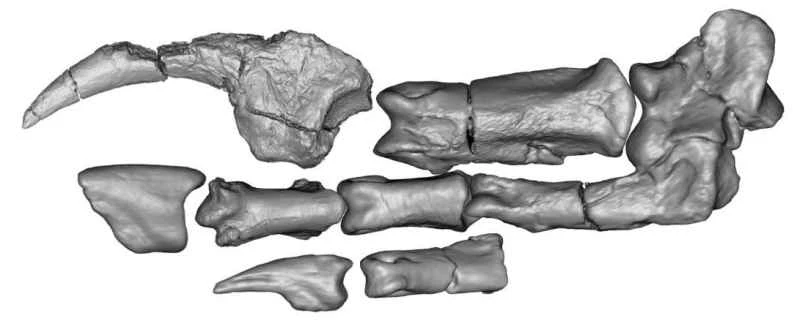

These two new alpharesaurid fossils are found precisely in the middle of this 90-million-year geological interval, that is, between the early and late alpharesaurids on a timescale. Their discovery provides crucial evidence for the hypothesis that alpharesaurids originated in Asia as a monophyletic group and gradually spread to other continents. *Hemiclawosaurus* and *Xygnatha* possess some typical features of late alpharesaurids, such as specialized and enlarged first claws, a highly mechanically efficient forearm structure, and a robust humerus. However, the relative proportions of their forelimbs are closer to those of primitive alpharesaurids, and quite different from the extremely short forelimbs of late alpharesaurids. Based on this, morphological observations of Hemiclawosaurus and Xylocera have gradually revealed the macroevolutionary process of the forelimbs of Alvarezsaurids: from the relatively long "grasping" forelimbs (such as those of the early Alvarezsaurids that were close to those of primitive theropods, to the forelimbs of Hemiclawosaurus and Xylocera with longer forelimbs and specialized claws, and then to the highly specialized, shortened, functionally single-fingered forelimbs of the later Alvarezsaurids.

Figure 3. The strangely shaped hand of Bannykus wulatensis (Image provided by Xu Xing)

“This transformation has continued gradually for nearly 50 million years,” said researcher Xu Xing, the author of the article. “Perhaps one day, the evolutionary history of the Alvarezsaurids may become a classic example of macroevolution, like the North American ‘horse fossil sequence’.”

“Alvarezsaurids are an incredible group of animals,” explains Dr. Choiniere of the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, a co-author of the paper. “They had strong hands with large claws, but their jaws were very slender, like aardvarks and anteaters among dinosaurs.” Interestingly, early alvarezsaurids had typical carnivorous teeth and hands better suited for grasping prey. Only later alvarezsaurids evolved large single claws, which were likely used to dig and destroy decaying wood and anthills to feed on the ants or termites inside. The fossils of *Hemiclawosaurus* and *Clawosaurus serratus* demonstrate the process by which alvarezsaurids gradually adapted to this new diet, making them extremely important.

“These fossil records are one of the best demonstrations of how anatomical features evolved,” said Professor Clark, a co-author of the paper. “Like other paradigms often mentioned in evolutionary biology, such as the ‘horse fossil sequence,’ these dinosaurs show how organisms in an evolutionary lineage changed their ecological niche over time (from carnivores to insectivores).

Figure 4. A reconstruction of a representative species of Alvarezsauridae, showcasing the fascinating evolutionary history of its forelimbs. (Image provided by Xu Xing, illustration by Vikto Radermacher)

Dr. Roger Benson of Oxford University added, "The two new fossil specimens have very long forelimbs, indicating that the Alvarezsaurids evolved short forelimbs relatively late in their evolutionary history. Interestingly, these short-armed dinosaurs were very small (less than a meter in length). This differs from another more well-known group of dinosaurs with shortened forelimbs—the Tyrannosaurids—who, despite their short forelimbs, were often enormous."

Figure 5. Researcher Xu Xing, the author of this article, and collaborator Professor James Clark conducting field research in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Photo provided by Xu Xing).

Over the past few decades, China has unearthed some of the most important dinosaur fossil specimens. "Our international field expeditions have yielded fruitful results in recent years," said researcher Xu Xing. "This study only shows the tip of the iceberg of our amazing discoveries."