A scientific expedition team led by Professor Wang Xiaolin from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, after more than ten years of continuous field research, discovered and salvaged an important specimen in the Lower Cretaceous strata of the Hami Gobi Desert in Xinjiang. This specimen contains over 200 pterosaur eggs, embryos, and skeletal fossils preserved in a three-dimensional arrangement. Sixteen of the pterosaur eggs contained three-dimensional embryo fossils, marking the world's first discovery of 3D pterosaur embryos. On December 1, 2017, the journal *Science* published online the significant findings of an international collaboration between Chinese and Brazilian scientists regarding the discovery of pterosaur eggs and embryos in Hami. This is another important discovery following the finding of numerous male and female Hami pterosaurs and the world's first three-dimensionally preserved pterosaur egg in the Hami Gobi Desert in 2014.

Pterosaurs were the first and only extinct flying vertebrates on Earth. Due to their need for flight, they evolved slender, hollow skeletons, making pterosaur fossils extremely rare worldwide, with pterosaur eggs and embryos being even rarer. Besides the five pterosaur eggs previously reported in the Hami pterosaur fauna, a total of six pterosaur egg fossils have been reported worldwide. Of the three specimens containing pterosaur embryos, two are from China and one from Argentina. The other three pterosaur eggs did not preserve embryos; two of these were preserved alongside a laying mother of a *Pterosaurus* species from the Yanliao Biota in China. These pterosaur eggs were all preserved in a two-dimensional flattened form; only one three-dimensionally preserved pterosaur egg was found in Argentina. Although some progress has been made in the study of pterosaur egg fossils, the scarcity of fossils and the fact that most are two-dimensionally preserved makes many biological questions, such as embryonic development and reproductive strategies, difficult to explain.

In 2014, *Current Biology*, a journal under *Cell*, featured a cover article reporting the discovery by Wang Xiaolin's team in Hami, Xinjiang, my country, of a large number of three-dimensionally preserved male and female *Hami pterosaur* individuals and their five egg fossils. This was the world's first report of three-dimensionally preserved pterosaur eggs. Although these pterosaur egg fossils did not preserve embryos, they provided researchers with a clear understanding of the eggshell structure of pterosaurs. The Hami pterosaur eggshell has a double-layered structure composed of a thin calcareous outer layer and a thick inner shell membrane, remarkably similar to the "soft-shelled eggs" of some extant reptiles, such as the rat snake. The discovery and study of this new pterosaur group, *Hami pterosaur*, and its egg fossils have made significant progress in areas such as sexual dimorphism in pterosaurs, ontogeny, the microstructure of pterosaur eggs and their shells, reproduction, and ecological habits. This discovery is considered "one of the most exciting discoveries in pterosaur research in 200 years," and a British paleontologist even wrote a commentary entitled "Which came first, the pterosaur or the pterosaur egg?"

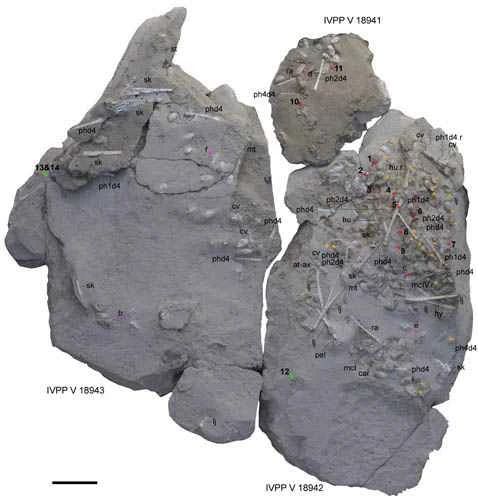

Hundreds of 3D pterosaur eggs and embryo fossils have been discovered in Hami, confirming that pterosaurs lived in groups. During a long-term field investigation in the Hami region, the research team led by Wang Xiaolin has diligently explored thousands of square kilometers of the Gobi Desert for over a decade, clarifying the distribution, enrichment, and burial patterns of pterosaur and dinosaur fossils. The pterosaur fossils are mainly found in a set of storm-deposited grayish-white lacustrine sandstone containing red mudstone fragments. The storm-deposited layers rich in pterosaur eggs and skulls are approximately 10-30 cm thick. On a 2.2-meter section, eight layers are rich in pterosaur fossils, four of which contain pterosaur egg fossils. The specimens studied this time consist of three interconnected sandstone blocks, with an exposed area of approximately 3.28 square meters. 215 pterosaur egg fossils have been exposed, and the number may be even greater, possibly reaching 300, including those that are not fully exposed underneath. There are also more than ten skulls and mandibles, as well as numerous postcranial skeletons. This stunning and exquisite fossil specimen includes fossilized eggs containing embryos that were scattered during field collection. A total of 16 pterosaur eggs containing embryos have been confirmed so far. The discovery of a large number of pterosaur eggs, embryos, and skeletal fossils such as skulls indicates that the Hami pterosaur had a gregarious lifestyle, and this site was likely one of its breeding and egg-laying locations.

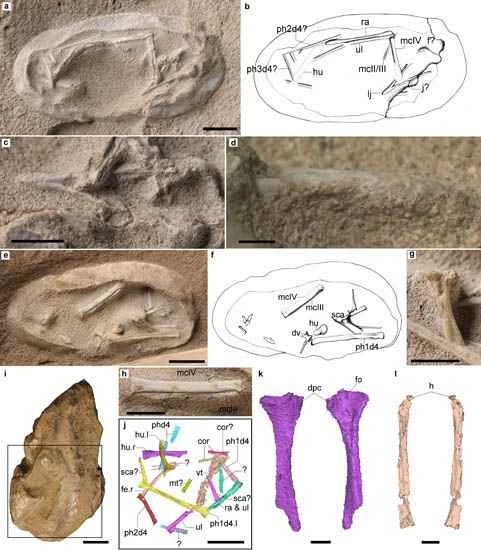

CT reconstruction and embryonic development studies have for the first time demonstrated that pterosaur hind limbs developed faster than forelimbs, and that hatchlings could only walk, not fly. Previously, due to the scarcity of pterosaur egg and embryo research materials, paleontologists had very limited understanding of pterosaur embryonic and reproductive development. This study has made several important advances in this area. Microscopic repair or CT scans were performed on 42 pterosaur egg fossils, 16 of which preserved embryos. Microscopic observation of their internal structures revealed that the embryonic fossils were generally incomplete, with bones ranging from one to several. This could be due to different developmental stages of the embryos or differences in bone preservation, such as loss or damage during transportation and burial. Given that the large number of pterosaur egg fossils clustered together involved short-distance transport caused by storms, and the characteristic of pterosaur eggs being "soft-shelled," varying degrees of embryonic fossil loss in all pterosaur eggs is normal, making it difficult to determine the developmental stage of the embryo in each egg. To address this issue, it was assumed that embryos at the same developmental stage were of similar size, allowing for comparison of bone length to confirm the degree of pterosaur embryonic development. Three embryos (Nos. 11, 12, and 13) have humeri of similar length, indicating they are at similar or identical embryonic developmental stages. Another embryo (No. 7) has a humerus approximately 20% longer than the other three, suggesting a later developmental stage. The smallest juvenile pterosaur humerus fossil discovered so far is approximately 18% and 40% longer than Nos. 7 and 13, respectively. Combined with previously collected humeri from subadult individuals, researchers have obtained a series of Hami pterosaur humerus sequences from different embryonic developmental stages to subadulthood. In this series of humeri, the deltoid crest accounts for 25.5%–27.8% of the total humerus length from embryo to hatching, and 31.5%–37.1% in subadult individuals. This research method was previously used in the study of the Southern Pterosaur from Argentina to infer the developmental stage of the pterosaur. The Hami Pterosaur is consistent with the changes in the deltoid ridge of the humerus of the embryos and sub-adult individuals of the only known Southern Pterosaur that are close to hatching. Therefore, it is inferred that embryos 11 to 13 are all in the late developmental stage, but the degree of development is not as high as that of the Southern Pterosaur embryos.

Embryo No. 12 is the only specimen with a preserved skull. After microscopic restoration, the almost complete ventral surface of the mandible was exposed, but the dentition fusion was unfused, and no trace of teeth was found. Since teeth are usually quite strong and easily preserved as fossils, the absence of teeth here is difficult to explain by preservation methods. Currently, teeth have only been preserved in the world's first pterosaur embryo discovered in the Jehol Biota of western Liaoning, differing from the embryonic development of *Hamiptosaurus*. It is speculated that the *Hamiptosaurus* embryo may have been in an intraocular developmental stage before tooth development, or, unlike the embryonic development of lizards and crocodiles, its teeth may have erupted late.

Embryo No. 13 had the most complete skeletal preservation among all the embryos and underwent CT scanning and 3D reconstruction at the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, Chinese Academy of Sciences. A very interesting phenomenon was discovered: although the femur of the Hami pterosaur embryo was fully developed, possessing a femoral head consistent with sub-adult or adult individuals and a significantly constricted femoral neck, suggesting that Hami pterosaurs likely possessed the ability to walk on land after hatching; simultaneously, the humeri on both sides were not fully developed and lacked the curved deltoid ridge, the location where pterosaurs attached their flight-related pectoral muscles. This suggests that pterosaurs likely did not possess flight capabilities after hatching, only the ability to walk.

This phenomenon of incomplete forelimb development was also observed in embryo number 11. This time, it was the scapula. In subadult or adult pterosaurs, the scapula develops a prominent scapular process, even in the smallest juvenile individuals. This structure is where the teres major muscle attaches, a crucial muscle for lifting wings during flight. However, this structure was not developed in the scapula of embryo number 11, suggesting that the Hami pterosaur may not have been capable of flight after hatching.

Based on the above studies of embryos, scientists believe that the hind limbs of *Hamiptosaurus* developed faster than its forelimbs. The hatchlings were capable of ground movement but could not yet fly because their teeth erupted late. They were also likely unable to hunt independently and required feeding or care from their parents. This presents a new hypothesis or viewpoint: although it represents a relatively precocious embryonic development pattern, pterosaur embryonic development was not as precocious as previously thought, and still required care from adult pterosaurs.

Bone histological studies have revealed that pterosaurs exhibited rapid skeletal growth and development, providing the first glimpse into their growth and development history. Due to the needs of flight, the bone walls of pterosaurs were very thin, and the interiors were mostly hollow. This manifests in the bone tissue as a rapid expansion of the medullary cavity, which prevented the preservation of the cancellous bone in the center and the compact bone near the center, as these were occupied by the rapidly expanding medullary cavity. Therefore, to understand the ontogenetic stages and other physiological information of pterosaurs through bone histology, a series of complete individual specimens from juvenile to adulthood are required. To date, few pterosaur types have provided such comprehensive fossil material. Currently, only the *Australopithecus africanus* from Argentina has been the subject of bone histological studies from juvenile to adult individuals.

Scientists selected two embryos and several long bones from juvenile to near-adult individuals of the pterosaur Hami for research, marking the world's first histological and microscopic study of pterosaur embryos. They discovered that pterosaur embryos were primarily composed of woven bone, a type of bone tissue containing numerous blood vessels, representing the fastest rate of bone growth and a type of bone tissue typically found only in the embryonic and infancy stages. Several upper limb bones of varying sizes from juvenile to sub-adult were mainly composed of fibrous bone, another type of bone tissue with a relatively fast growth rate, indicating that pterosaurs had a rapid growth and development rate. However, differences existed at different growth and development stages: juvenile individuals only had fibrous bone; sub-adult individuals developed an inner ring-shaped bone plate, a slowly growing secondary bone tissue, indicating that the medullary cavity had stopped growing and was a sign of sexual maturity; near-adult individuals not only had their medullary cavity stop growing, but also exhibited two growth arrest lines on the outermost layer, marking the organism's cyclical growth, representing one year. Therefore, the individuals closest to adulthood were at least two years old at death, but had not yet fully reached adulthood.

The unique burial characteristics of the fossils indicate that a large lacustrine storm event caused the death of pterosaur colonies and their rapid burial over short distances. Such a rich and uniquely preserved collection of pterosaur eggs and skeletal fossils is unparalleled worldwide. What caused this? Sedimentological and taphonomic observations revealed that the Hami pterosaur eggs and skeletal fossils primarily originated from a set of laterally unstable, grayish-white lacustrine sandstone rich in red mudstone clumps. These mudstone clumps were not transported from outside the basin but rather came from endogenous materials within the basin. The fossil enrichment layers are not very thick, and all fossils are invariably concentrated in high-energy storm deposits containing clumps. Although the skeletal fossils are scattered, each slender, hollow bone is almost entirely intact, and the long, thin skull teeth and delicate head ornaments are well-preserved and associated with the skull or mandible. Therefore, it is believed that these numerous pterosaur and pterosaur egg fossils likely experienced multiple lake storm events. These high-energy storms passed through the pterosaur nests, bringing the pterosaur eggs and pterosaurs of different sizes and sexes to the lake shore. After a short period of floating and gathering, they were quickly buried along with the torn and scattered pterosaur remains.

One of the significant achievements of the Chinese Academy of Sciences' "Pioneering Action" program in continuously supporting basic research and actively participating in the national "Belt and Road" initiative is the discovery of pterosaurs and their eggs in Hami, Xinjiang. Since 2005, researchers including Wang Xiaolin, Zhou Zhonghe, Jiang Shunxing, Cheng Xin, and Wang Qiang, along with technicians such as Li Yan and Xiang Long, have collaborated with relevant departments of the Hami local government and Ma Yingxia of the Hami Museum, conducting over a decade of field investigations and fossil conservation work in the Hami Gobi Desert. The Chinese Academy of Sciences' "Pioneering Action" program, the National Natural Science Foundation of China's continuous support for basic research in paleontology and other fields, and the long-term funding from the Chinese Academy of Sciences for field excavations have played a crucial role in the significant discovery of pterosaurs and their eggs in Hami, Xinjiang. The Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) actively responded to the national "Belt and Road" initiative and strengthened their support for western my country, especially Xinjiang. In 2015, the IVPP signed a strategic cooperation agreement with the Hami Municipal Government to assist in the construction of local museums and the application for national geological parks. At the same time, the world's largest pterosaur fossil exhibition, "Flying to the Cretaceous - Chinese Pterosaur Exhibition," was held at the Hami Museum. With the support of the Xinjiang Association for Science and Technology and other relevant local departments, an academician and expert workstation and a research and scientific expedition base of the IVPP were established in Hami. These efforts assisted the local government and relevant departments in effectively protecting this important natural heritage and guiding its development planning, making it a model of cooperation between the CAS and local governments.

The Hami expedition team from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, kept in mind the mission of scientists and conducted continuous research for more than ten years under extremely harsh conditions in the Gobi Desert, achieving a series of important fossil discoveries. Today, this site has become the world's largest and richest pterosaur fossil site, with the first-ever discovery of numerous male and female pterosaurs at different developmental stages, hundreds of 3D pterosaur eggs, and pterosaur embryos, etc., which are of great significance for understanding and revealing the life history of pterosaurs and gaining a deeper understanding of the Cretaceous paleoenvironment, paleoclimate, and paleogeography. These research results are also one of the achievements of a long-term collaboration between a team of Chinese paleontologists led by Wang Xiaolin and a team of Brazilian paleontologists led by Professor Alexander Kellner, an academician of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences and the National Museum of Brazil. Since 2003, paleontologists from both countries have conducted long-term and extensive exchanges and cooperation in the fields of vertebrate paleontology, and have successively published a series of research results in internationally renowned journals such as Nature, Science, PNAS, and Current Biology. The cooperation between scientists from both countries in the field of paleontology is also one of the earliest collaborations between the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Brazilian Academy of Sciences. Wang Xiaolin and Zhou Zhonghe, the main researchers of the Hami pterosaur, were also elected as academicians of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences.

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Category B), the Field Excavation Funding and Key Deployment Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of the Chinese Academy of Sciences provided equipment and technical support for CT scans and bone tissue sections.

Figure 1. More than two hundred pterosaur eggs (IVPP V 18941-18943) preserved in sandstone. Red arrows indicate pterosaur eggs with embryos; green arrows indicate the locations of three pterosaur eggs as seen in CT scans; orange arrows indicate pterosaur eggs without embryos. The scale bar in the figure is 100 mm. (Photo provided by Wang Xiaolin)

Figure 2. Three-dimensionally preserved Hami pterosaur egg fossil. A: Detail magnification, scale bar 10 cm; BF: Egg fossils showing different degrees of deformation, scale bar 1 cm. (Photos provided by Wang Xiaolin)

Figure 3. Hami pterosaur embryo fossils: Embryo 12 (AD), Embryo 11 (EH), and Embryo 13 (IL). A & B: Photographs and line drawings of Embryo 12, the only Hami pterosaur embryo with a preserved skull, scale bar 10 mm; C: Enlarged view of the dorsal side of the mandible, scale bar 5 mm; D: Side view of the anterior end of the mandible (dorsal side up), scale bar 1 mm; E & F: Photographs and line drawings of Embryo 11, scale bar 10 mm; G: Scapula, scapula without attachment to the teres major muscle, scale bar 5 mm; I: Photograph of Embryo 13, the box indicates the location of the embryo, scale bar 10 mm; J: 3D reconstruction model of Embryo 13 after CT scan, scale bar 10 mm; K: Incompletely developed humerus, scale bar 2 mm; L: Almost fully developed femur, scale bar 2 mm. (Photos provided by Wang Xiaolin)

Figure 4. Ecological reconstruction of Hami pterosaur (illustrated by Zhao Chuang)