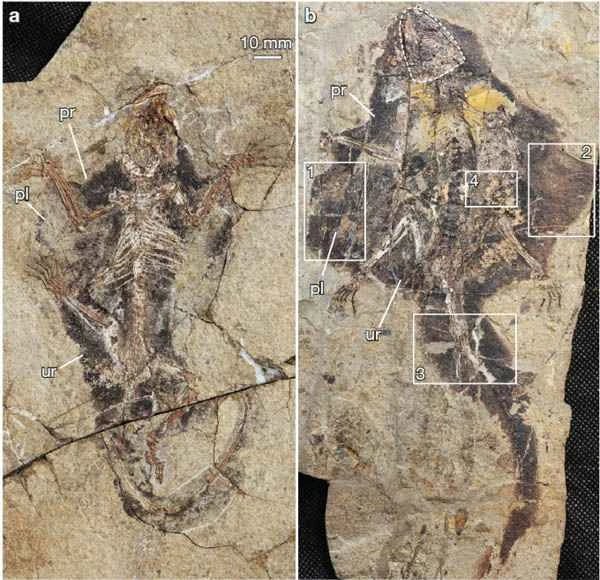

Researchers from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, along with several research institutions in China and the United States, jointly published their findings on a new species of tree thief—*Tree thief ahoi*—in the British journal *Nature* on November 13. The new specimen was discovered in the Tiaojishan Formation, Gangou Town, Qinglong County, Hebei Province, dating to the Early Late Jurassic (approximately 164-159 million years ago), belonging to the Yanliao Biota. The new material not only preserves the best-preserved details of gliding dermal morphology and hair imprints among thief-like mammals to date, but also preserves the earliest and most complete middle ear structure among Mesozoic mammals, which is of great significance for understanding the diversity of Mesozoic mammals and the evolution of the mammalian middle ear.

The scalythidae are an extinct group of mammals that lived in the northern continents from the Late Triassic to the Late Jurassic. They are one of the earliest groups of mammals, and their taxonomic status has been controversial. Fossil specimens of scalythidae were first discovered in Europe as early as 1847. Since then, although new materials have been discovered, the vast majority of specimens consist of scattered teeth, with only a few fragmented jawbones. It wasn't until the 2013 publication of *Kingstreetosaurida*, along with subsequent reports of other scalythidae such as *Shensuo*, *Xiansuo*, *Xiangchisuo*, and *Zuyisuo* in *Nature*, that important morphological characteristics of this extinct mammal group from geological history were gradually revealed.

The tree thief of Aho's body has a slender skeleton with elongated fore and hind limbs, a main lateral wing between the fore and hind limbs, a forearm between the neck and forelimbs, and a tail wing between the tail and hind limbs. The dermal wings are covered with regularly arranged hairs, and the tail is long and can spread out. Their hands and feet have elongated phalanges (toes), demonstrating skeletal features indicating grasping and climbing abilities. These combined characteristics are very similar to gliding species among extant marsupials and rodents. To date, all species of thieves in the Yanliao Biota date from approximately 164-159 million years ago, exhibiting arboreal adaptations and gliding capabilities. They represent a highly diverse arboreal group in the Jurassic forest environment, second only in age to the earliest known Mesozoic gliding mammal published in 2006, the gliding mammal found in Daohugou, Ningcheng, Inner Mongolia (approximately 168-164 million years ago), which also belongs to the Yanliao Biota.

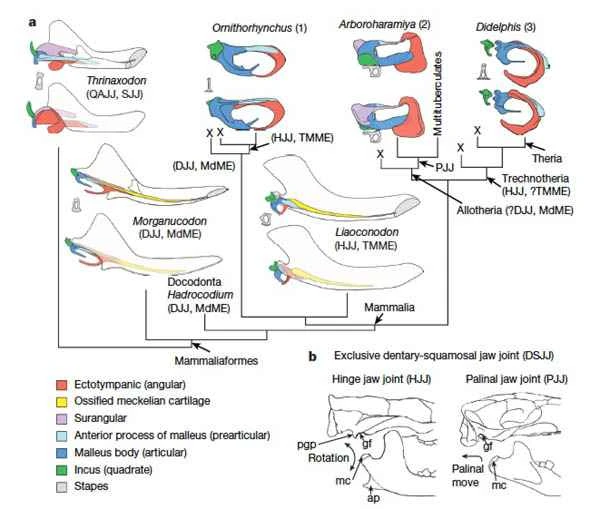

Besides its gliding features and intricate structures, *Arboriformes ahoi* also preserves one of the most complete middle ear structures among early mammals. The evolution of the mammalian middle ear has been a classic topic in vertebrate evolution. Since at least 1837, it has been recognized that the ossicles of the mammalian middle ear evolved from several bones associated with the jaw joints of reptiles. The mammalian middle ear is generally considered to consist of the stapes, incus, and malleus, in addition to the ectotympanic bone supporting the eardrum. In contrast, the reptile middle ear has only one columella (stapes). In the reptile mandible, besides the dentary bone to which the teeth are attached, there are several postdentary bones: the prearticular bone, articular bone, ectotympanic bone, and maxillary bone. Based on numerous studies in developmental biology and paleontology, it is generally accepted that the mammalian malleus is homologous to the prearticular and articular bones of the reptile mandible, the ectotympanic bone is homologous to the ectotympanic bone of the reptile mandible, and the incus is homologous to the quadrate bone of the reptile skull. However, the middle ear region of *Ahoschizothorax ahoschi*, in addition to the aforementioned bones, also retains the superior cusp bone, which is absent in the middle ear of any known mammal. These tiny bones, largely preserved in situ and completely detached from the mandible, exhibit characteristics typical of a mammalian middle ear, but differ significantly in morphology from the corresponding bones in the middle ear of currently known mammals, representing a completely new type of mammalian middle ear. The emergence of this type may be related to the unique jaw joint formation and chewing movement patterns of *Ahoschizothorax*.

The discovery of the middle ear of *Arborea arborea* provides crucial morphological information and raises many challenging questions about the evolution of the middle ear in mammals, offering significant insights. To date, no research has answered the question of the fate of the superior ossicle in the postdentary bones of mammal-like reptiles. The presence of the superior ossicle in *Arborea* suggests that during the evolution of the mammalian ear region, it, like other auditory ossicles, entered the ear region and became part of the auditory organ. Therefore, the superior ossicle may have existed in the middle ear in other early mammalian groups, but may have fused with other bones or been lost during later evolution. This new discovery will encourage paleontologists to pay closer attention to the evolution of the mammalian middle ear, especially the fate of the superior ossicle. It will also provide developmental biologists with new clues, prompting them to consider the possibility of the superior ossicle in their studies of the development of extant mammals. Combined with new mammalian phylogenetic studies, the middle ear of *Arborea arborea*, and the middle ears of extant mammals such as therapsids and monotremes, should have evolved independently. This demonstrates that the delicate and complex structures of the middle ear ossicles, which possess important sensory capabilities, and the gliding locomotion, have evolved independently multiple times in mammals.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) Basic Science Center Project "Craton Destruction and Terrestrial Biological Evolution," the NSFC, and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Category B). Three-dimensional scanning of the fossils was performed at the High-Precision Computed Tomography (CT) Center of the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Original link: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature24483

Figure 1: Tree thief of Aho, an early Late Jurassic animal, with wing membranes and hair imprints (Photo courtesy of Mao Fangyuan)

Figure 2: Parallel evolution of the middle ear in mammals (Image provided by Mao Fangyuan)

Figure 3: Reconstruction of the Tree Thief Beast of Aho (drawn by Shi Aijuan)