Elephants are the largest land mammals, belonging to the order Proboscidea. The order is represented by only three extant elephant species: the African savanna elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. However, the evolutionary history of Proboscidea is exceptionally rich, with fossils of at least 180 species discovered. In particular, Proboscidea is one of the few extant orders of mammals whose fossil representations can be found in the Paleocene. Although molecular biology suggests that the major extant orders of mammals, including primates, diverged before the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event 65 million years ago, this is merely a theory and lacks sufficient fossil evidence to support it. The earliest known representative of Proboscidea, the Eritherium, was discovered in Morocco, Africa, approximately 60 million years ago during the Paleocene.

Africa holds a unique place in the geological history of the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras. Since the Middle Jurassic period, 165 million years ago, the supercontinent Pangaea broke apart, separating the African plate from other continents by oceans. Early mammals began to evolve independently on the African continent, giving rise to a group known as the Afromatidae superorder. The descendants of this group branched out from Africa and evolved to include species with vastly different morphologies and ecological adaptations. From tiny creatures like elephant shrews and golden moles, to hare-like hyraxes, termite-eating aardvarks, to manatees fully adapted to marine life, and even the giant land mammals, such as the elephants—our subject in this article—they may all have descended from a common Afromatidae ancestor. Around 20 million years ago, the African and Eurasian continents collided, and the mammals of these two continents, separated for hundreds of millions of years, reunited. Among the most prominent were proboscis mammals, which traveled further than most African mammals, eventually distributing to several continents except Australia and Antarctica—but that's another story. However, we need to remember the African origin of proboscis, because the vast majority of later branches of proboscis, despite their wide global distribution, often originated in Africa. This seems somewhat similar to humans, but human ancestors may have originated in Asia before the Oligocene (about 34 million years ago). After the Oligocene, the center of evolution for primates and humans shifted to Africa.

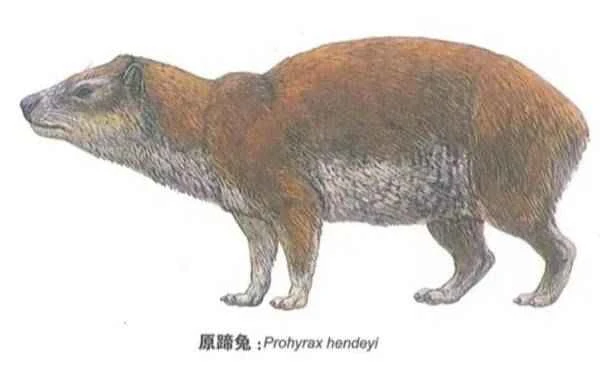

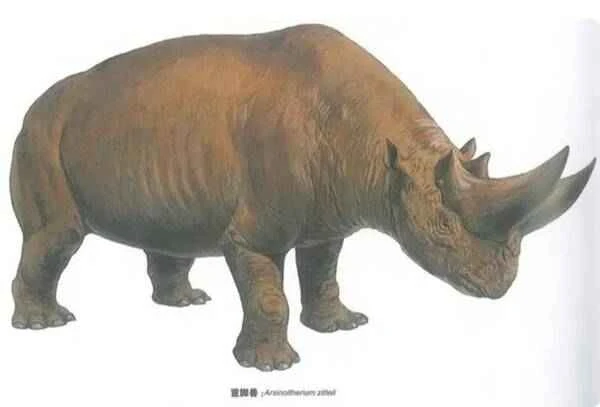

Let's return to the evolution of proboscideans. Among extant groups, the closest relative to Proboscideans is the order Sirenia. It's hard to imagine an elephant having a distant aquatic relative; however, Sirenia also possess tusk-like incisors similar to elephants, as well as replacement cheek teeth, all indicating a close kinship. Another extant group closely related to Proboscideans is the hyrax, about the size of a rabbit, living in Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, but historically also distributed in China and other regions. In addition, there are two other fossil groups: one is the Baryopoda, enormous in size, with the Egyptian Baryopoda possessing two pairs of enormous horns, one large and one small; the other is the Corylotheriformes, a strange, large, semi-aquatic mammal distributed along the Pacific coasts of Japan, the United States, and other places. These strange animals, together with Proboscideans, form the subungulates, representing a vast evolutionary lineage.

Original hoof rabbit

Since the emergence of the Dawn elephant in the Paleocene epoch 60 million years ago, proboscis embarked on an independent evolutionary path. This is the first of three stages in the evolution of proboscis. At that time, the Dawn elephant weighed only 3 to 8 kilograms, roughly the size of a rabbit. However, its molars had already evolved some characteristics of later Eocene proboscis, namely a tendency towards double-ridged molars. Note that this feature is quite different from the molar characteristics of later elephants. Around 55 million years into the Eocene, the Phosphatherium evolved, still found in Morocco, Africa. At this time, the Phosphatherium weighed 10 to 15 kilograms, about the size of a small pig, and its shape also resembled a small pig. The Phosphatherium's molars developed into true double-ridged tusks, a typical feature of proboscis in the first stage; its upper and lower second incisors began to enlarge, and in the future, these enlarged incisors would evolve into true tusks, one of the typical features of modern elephants; while the most important feature of proboscis, the long nose, showed no signs of development at this time. Contemporaneous with or slightly later than the Phosphorus elephant, proboscideans included the Daouitherium and Numidotherium, which reached the size of tapirs and became mere passersby in the early evolutionary path of proboscideans. Around 40 million years ago, during the late Eocene, a truly colossal creature emerged among proboscideans: Barytherium, nearly 2 meters tall at the shoulder and weighing about 2 tons. Since its discovery, Barytherium had been considered a mysterious animal until its cranial skeleton was discovered, revealing that 40 million years ago, Barytherium already possessed some characteristics of modern elephant cranial skeletons, demonstrating that large body size was an early evolutionary trend among proboscideans. A large body was of great significance for proboscis to protect themselves and resist natural disasters. In particular, later proboscis evolved a flexible proboscis that could grasp like a hand, solving an evolutionary problem for other large animals. This led to the continued prosperity of proboscis for tens of millions of years in the Late Cenozoic Era, but that's another story.

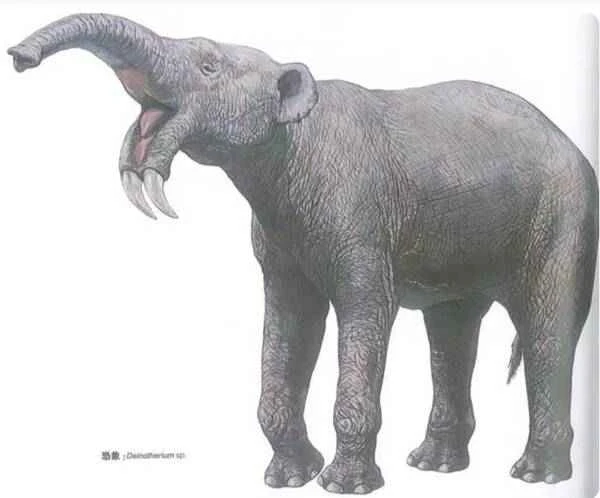

As we've discussed with the Phosphorus Elephant, the first stage of proboscidean evolution is characterized by double-ridged molars, a feature that reached its peak in the well-known Deinotheirum and represents the final remnant of this first stage of proboscidean evolution. Deinotheirum fossils are scarce in the Early Oligocene. Around 25 million years later in the Late Oligocene, the first Deinotheirum appeared: the Ethiopian Chilgatherium. This was followed by the Prodeinotheirum and Deinotheirum, which, along with the pediformes and mammoths discussed later, spread to Europe and Asia. Deinotheirum was a very large animal, weighing over 10 tons, placing it among the largest proboscideans. It lacked upper incisors but possessed a pair of downward-curving hooked lower incisors, suggesting its nose was not particularly long. It is particularly noteworthy that no Deinotheirum fossils were found in China before the beginning of this century, seemingly establishing that Deinotheirum did not enter the Chinese region. However, this hypothesis was overturned in 2007 when a research team led by Academician Qiu Zhanxiang and Researcher Deng Tao discovered fossils of *Protodon sinensis* from the early Late Miocene (approximately 10 million years ago) in Dongxiang County, Gansu Province. This discovery provided solid evidence of *Protodon sinensis*'s entry into China. The reason for this discovery is likely that *Protodon sinensis* inhabited southern China before the Late Miocene, as evidenced by reports of this period in Thailand and Myanmar. However, strata from this period are missing in southern China, thus leaving no fossil record of *Protodon sinensis*. At the boundary between the Middle and Late Miocene, a mass extinction occurred in northern China, completely wiping out the once-thriving *Shovel-tusked* and *Gnaphaltus* species. This created ecological space for *Protodon sinensis* in the south, allowing them to migrate north and leave this invaluable record in the Linxia region of China. As the climate cooled further during the Late Miocene, *Protodon sinensis* had to retreat from northern China and gradually disappeared across Eurasia. The last *Protodon sinensis* became extinct in Africa during the Middle Pleistocene (around 100,000 years ago).

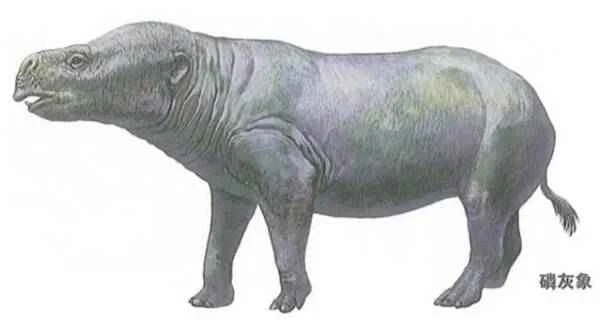

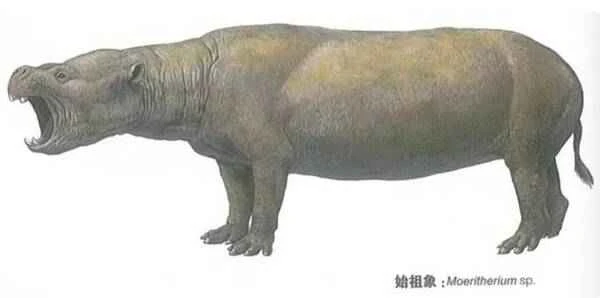

Returning to Late Eocene Africa, another proboscidean that coexisted with giant mammals is the more famous *Moeritheirum*, commonly known as the ancestral elephant. It was long considered the direct ancestor of elephants. Later discoveries of fossils such as the Phosphorus elephant gradually changed this view. The postcranial morphology of *Moeritheirum* indicates that it was adapted for amphibious life, like today's hippopotamus. It also possessed enlarged incisors but lacked a long trunk. The molars of *Moeritheirum* began to evolve towards a hummoid shape, altering the early proboscidean biridged molar paradigm and foreshadowing some future evolutionary directions for proboscideans, although the evolution of *Moeritheirum* may have deviated from the main evolutionary line of proboscideans.

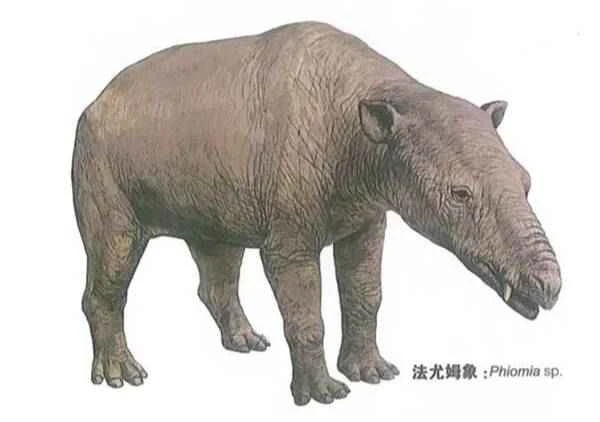

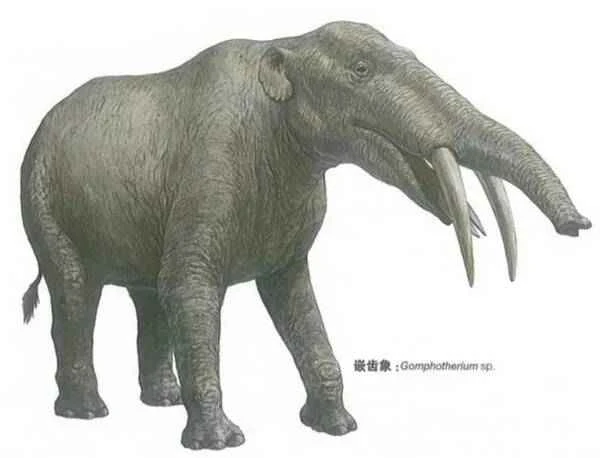

After the ancestral elephant, the evolution of proboscis entered its second stage. It was during this stage that proboscis successfully spread globally, marking the beginning of their true prosperity. It was also during this stage that proboscis truly evolved long trunks, although these trunks may not have been as agile as those of modern elephants. Therefore, proboscis of this period truly became a group with long trunks. At the beginning of this second stage, the most distinctive feature of proboscis was the elongation of the lower jaw, with particularly enlarged upper and lower second incisors. The upper teeth became tusk-like, while the lower teeth became shovel-shaped or club-shaped, becoming powerful feeding tools. The trunk served merely as an auxiliary tool, used in conjunction with the incisors and lower jaw for feeding. From this period onward, proboscis acquired a more familiar name: elephants, specifically the suborder Elephantoformes. However, species such as the Phosphorus Elephant, Mohu Beast, and even the Deinonychus cannot be taxonomically classified as elephants. Elephants abandoned the double-ridged structure of the first stage in their molars, with the number of ridges gradually increasing, transforming into a mound-ridged or completely mound-shaped structure. Because the tips of their teeth resemble nipple-like projections, elephants of this stage are collectively known as mastodons. Masodons' teeth began to evolve towards horizontal replacement, implicitly pointing to the third stage, which will be discussed later. The earliest mastodons are represented by the Palaeomastodon and Phiomia of Africa in the early Oligocene (approximately 30 million years ago). They were already quite large animals at that time, with elongated trunks and lower jaws, and shovel-shaped lower incisors, clearly powerful foraging tools. After a slow development throughout the Oligocene, mastodons underwent a large-scale divergence at the beginning of the Miocene (around 25 million years ago), initially differentiating into two major groups: the mammoths and the pediformes, represented by the Losodokoddon and the Eritrean elephant, respectively. Although some clues from South Asia and China suggest that proboscis may have reached southern and eastern Asia as early as 20 million years ago, their large-scale entry into Eurasia occurred in the middle of the Early Miocene (around 18 million years ago), forming the so-called pediform land bridge event, which became an important marker of the re-interconnection of Africa and Eurasia in geological history. Also in the early Middle Miocene, mastodons evolved into four primary taxa: the mammoths, pediformes, hog-toothed mastodons, and shovel-toothed mastodons. All of these mastodons initially possessed elongated mandibles and molars with three ridges or ridges, hence the name triangular-jawed mastodons. Of these four families, the molars of the Mammothidae family are ridge-shaped, while those of the other three families are also ridge-shaped, distinguished by differences in the morphology of the lower jaw and lower incisors. The Shovel-tusked Elephant family inherited the shovel-shaped lower incisors of the Fayum Elephant, with a further widening of the lower jaw; the Incidontidae family's lower jaw narrowed, and the lower incisors became rod-shaped; while the Hog-toothed Elephant is the most unique, with a long, groove-shaped lower jaw, but the lower incisors are degenerate, with only keratinous, blade-like structures extending from the front to replace them. These differentiations demonstrate that mastodons took broad strides in different directions, proudly advancing in adapting to various ecological environments. During this period, the Mammalidae family was represented by the African Eozygodon and the Eurasian Zygolophodon, both of which were mastodons with highly ridged teeth. The Hog-tusked Elephant family was represented by the African Afrochoerodon and the Asian Choerolophodon. The Gomphotherium family was represented by the Gomphotherium, which was found throughout Eurasia and Africa. The Platybelodon family was particularly prosperous, with Archaeobelodon and Protanancus found in both Eurasia and Africa, while the Platybelodon flourished in northern China. The Platybelodon possessed an exaggeratedly shovel-shaped lower jaw and incisors. Although early evidence suggested they lived near water and fed on aquatic plants, later evidence indicates they likely lived in semi-open areas of sparse forests, using their incisors to cut vegetation for food. In many locations in China during the Middle Miocene, such as Linxia in Gansu, Tongxin in Ningxia, and Tonggur in Inner Mongolia, the shovel-tusked elephant was the most common member of the fauna, far outnumbering other large mammals.

Fayoum Elephant

Yoke-toothed elephant (Image from the internet)

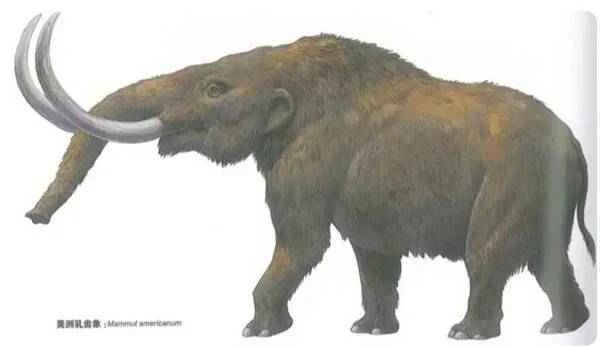

At the beginning of the Middle Miocene (around 16 million years ago), the Miomastodon, a member of the Mammothidae family, was the first to cross the Bering Strait and reach North America. Other groups within the Miomastodon family followed suit, becoming important members of the North American mammalian fauna. Later, it was observed that while the evolution of mastodons in Eurasia encountered significant setbacks in the Late Miocene, North America became the final refuge for many long-jawed mastodon groups. For example, the Amebelodon, a member of the Shovel-tusked family, lived in North America until the very end of the Miocene (~6 million years ago) and evolved the largest mandible among land animals. The Gnatabelodon, a member of the Pig-toothed family, also survived until the middle of the Late Miocene (~7 million years ago). The American mastodon (Mammut americanum) of the Mammodontidae family successfully survived in North America until the beginning of the Holocene (~10,000 years ago), while the descendants of the grostodon entered South America in the late Pliocene, creating the last prosperity of mastodons and also surviving until the beginning of the Holocene. However, both the American mastodon and the South American grostodon had evolved into short-jawed elephants, which will be discussed further below.

The period from the latter half of the Early Miocene to the end of the Middle Miocene (18-11 million years ago), spanning seven to eight million years, was the peak evolutionary period for mastodons. Various species of triangular-jawed mastodons occupied the ecological space previously held by large herbivores. However, they were unaware that an evolutionary crisis was quietly approaching. This period of triangular-jawed mastodon prosperity coincided with the "Middle Miocene Optimum" in geological history, which is also the last warm period globally to date. The mastodons that thrived during this warm period could not have foreseen the survival challenges that the global cooling would bring after the warm period ended. Of course, this survival challenge was not only aimed at mastodons, but at the entire ecosystem. From 14 million years ago, the climate began to gradually cool, and forest ecosystems in mid-to-high latitude regions around the world tended to decline, while arid grassland ecosystems became the dominant ecological environment in mid-to-high latitude regions. Especially in most of the mid-to-high latitude regions of Asia, the rapid uplift of the Tibetan Plateau led to persistent aridification, culminating in a major reorganization of the Eurasian ecosystem around the mid-to-late Miocene epoch, approximately 11 million years ago. Studies show that no large mammal survived beyond this boundary in northern East Asia; the triangular-jawed mastodon, represented by the shovel-tusked elephant, suffered catastrophic extinction. Only a small number of triangular-jawed mastodons survived in the southern forests, barely clinging to life; or they lived in the Americas, where climate change was less drastic, as described above. Learning from this painful experience, some mastodon species evolved new survival strategies in the face of severe survival crises. First, the number of tooth ridges increased, evolving from three-sided to four-sided, and even more, to adapt to increasingly coarse plants. The second change was the complete horizontal replacement of molars; once one molar wore out, another would grow in, greatly extending the lifespan of molars. The most significant change was that, after 20 million years of refinement, the evolution of the long trunk in mastodons reached unprecedented heights in evolutionary history. Their trunks were dexterous enough to rival human hands, enabling them to independently perform foraging functions. Therefore, mastodons began to abandon their long jaws, and the lower jaw began to shorten. As mentioned earlier, a branch of ridge-type pedimentous mastodons in the Americas continuously shortened their lower jaws. After the Rhynchotherium stage, they evolved into the completely short-jawed Southern Mastodon (Notiomastodon) and Cuvieronius. At the end of the Pliocene, when the Isthmus of Panama formed, they rapidly spread into South America, becoming the dominant species there. Meanwhile, mammoths also evolved in Eurasia and the Americas, giving rise to the short-jawed Mammut borsoni and the American mastodon. Whether the American mastodon migrated from Eurasia during the Pliocene (around 5 million years ago) or evolved from native mammoths remains a highly controversial topic. Perhaps similar to human evolution, mammoths underwent more than one migration and assimilation event from Eurasia to the Americas. Although these American mastodons had completely shortened jaws and eventually lost their lower incisors, they still retained the primitive triangular molar pattern.

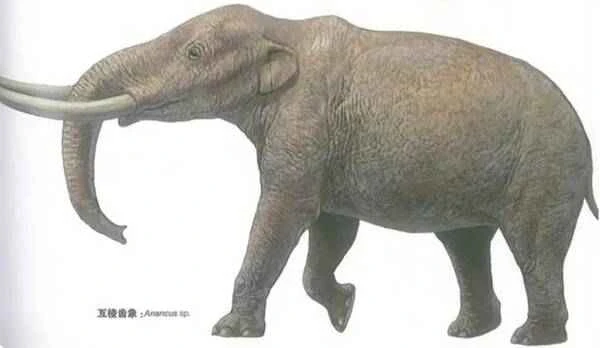

The true evolutionary leap occurred in Eurasia and Africa during the Late Miocene, giving rise to three branches from the hummock-shaped serpentine elephant. The more conservative branch, by its evolutionary end, only evolved quadrangular teeth, albeit with a change in the arrangement of the ridges—this is the Anancus. The other two branches were more advanced, with teeth having eight or more ridges, reaching over twenty ridges by the Late Pleistocene. One branch originated in southern Asia, retaining its low-crowned molars to this day—the well-known Stegodontidae family. The other branch originated in Africa, the cradle of proboscidean evolution, and is the only surviving proboscidean—the Elephantidae family, or more specifically, the True Elephant family. With the emergence of Stegodontidae and True Elephants, proboscideans had reached their third stage of evolution, representing their final flourishing.

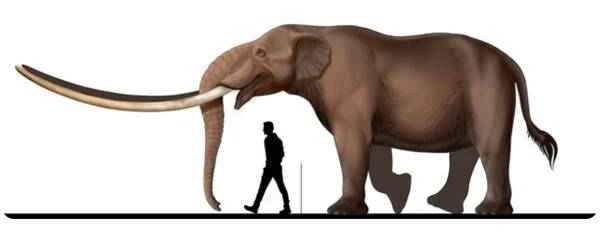

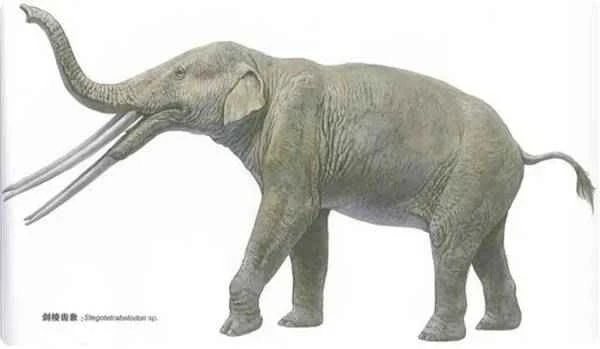

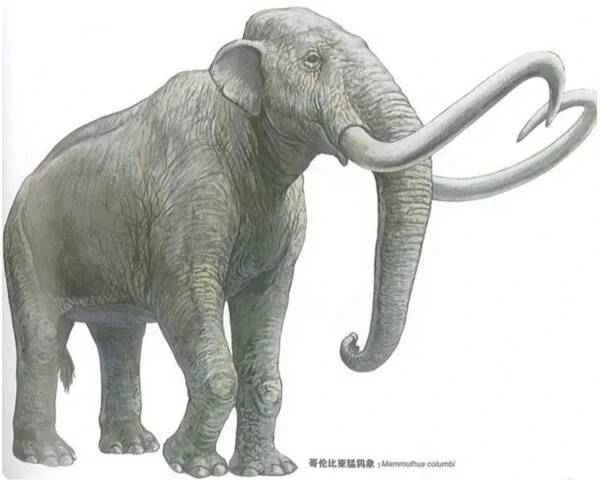

Stegodon, an ancestor of the Stegodon, exhibited remarkably advanced features very early on. In the late Early Miocene, while other elephants still possessed triangular molars and long jaws, the Stegodon's jaw had already begun to shorten, and its molars evolved into a quadrangular shape. Centered in Southeast Asia, the Stegodon spread only to China, Japan, and South Asia. It was the dominant elephant species in eastern China and Japan during the Miocene, demonstrating its adaptation to a relatively humid environment. By the very last period of the Late Miocene, approximately 6 million years ago, the Stegodon evolved into the Stegodon, appearing in Yunnan, China, specifically the Zhaotong Stegodon. However, puzzlingly, some reports of "stegodon" cheek teeth have also surfaced in Africa around 7 million years ago. Because a complete evolutionary sequence of early saber-toothed elephants was only found in eastern and southern Asia, and the early "saber-toothed elephants" in Africa emerged around the same time as true elephants, these African "saber-toothed elephants" are likely early versions of true elephants, with cheek teeth very similar in morphology. Those African "saber-toothed elephants" quickly became extinct, while Asian saber-toothed elephants flourished in the Early Pliocene (5 million years ago), spreading throughout northern and southern China. Among them was the Yellow River Elephant, which is featured in Chinese elementary school textbooks and praised in poetry. The Yellow River Elephant also became one of the largest proboscis species, standing nearly 4 meters tall at the shoulder and estimated to weigh up to 12 tons. With the Arctic ice cap remaining frozen year-round during the Late Pliocene (3 million years ago), and the climate rapidly cooling, saber-toothed elephants retreated south again. In China, the Early Pleistocene Proto-Eastern Saber-toothed Elephant and the Middle and Late Pleistocene Eastern Saber-toothed Elephant are representative examples. Similar species also existed in Southeast Asia and South Asia. Although the warm and humid climate of the south provided excellent refuge for saber-toothed elephants during the Pleistocene compared to the harsh north, they ultimately went extinct in southern China and on the planet around 10,000 years ago with the arrival of the Holocene. The Holocene was a period of global warming, theoretically more suitable for saber-toothed elephants, so why did they perish on the eve of their extinction? Research suggests that compared to their rivals, the Asian elephant, the saber-toothed elephant's food range was more limited, and this reduction in food sources may have been the main reason for their extinction during the Holocene warm period. The fate of their siblings, the true elephants, was even more turbulent. True elephants originated in Africa around 7 million years ago in the mid-Late Miocene. Unlike saber-toothed elephants, Africa in the Late Miocene already had a typical monsoon grassland climate. The relatively arid climate prompted true elephants to develop increasingly tall teeth from the beginning; their massive molars were lined with densely packed plates, resembling giant millstones, capable of crushing any coarse food. Early true elephants, though with a shortened lower jaw, possessed an exceptionally well-developed pair of lower incisors; this is the Stegotetrabelodon, with its four long tusks. Perhaps because four tusks were too many and not particularly useful, the Stegotetrabelodon quickly became extinct, giving rise to the Stegodibelodon and the Primelephas, which had only one pair of upper incisors. Afterwards, three main groups of true elephants emerged in Africa: the familiar African elephant (Loxodonta), the Asian elephant (Elephas), and the mammoth (Mammuthus). There is also a group called Palaeoloxodon; is it more evolutionarily close to the Asian or African elephants? Morphology and molecular biology offer different interpretations. The evolutionary history of the African elephant was mainly confined to Africa, while Asian elephants and mammoths spread to Eurasia during the Late Pleistocene, with the mammoth becoming the most dominant elephant species in northern Eurasia. In Eurasia, mammoths underwent different evolutionary stages: the Romanian elephant of the Late Pleistocene, the Southern elephant of the Early Pleistocene, the Steppe mammoth of the Middle Pleistocene, and the true mammoth (woolly mammoth) of the Late Pleistocene. The Southern elephant entered North America during the Middle Pleistocene and evolved into the Columbus mammoth. The Southern elephant, Steppe mammoth, and Columbus mammoth became the largest proboscis species, weighing close to 20 tons. The Paleodon amurensis could also reach this size. During the frigid Pleistocene, due to the periodic changes in the Earth's orbit around the sun, glacial and interglacial periods alternated. In Eurasia, the distribution of mammoths in high latitudes and Paleodon amurensis in mid-to-low latitudes fluctuated, with their distribution range showing rhythmic changes with the glacial and interglacial periods.

Saber-toothed elephant

During the more than two million years of the Pleistocene epoch, although rapid human development brought some challenges to elephants, they demonstrated remarkable adaptability to harsh environments, spreading across Eurasia, Africa, and North America. However, their ultimate fate still befell them. Similar to the saber-toothed elephant, the arrival of the Holocene Warm Period led to a fundamental decline in true elephants. The Paleodon and mammoth became completely extinct, although a very small population of mammoths still lived on islands in the Arctic Ocean off northeastern Russia around 3,000 years ago. Proboscideans were not the only victims of the Holocene. Along with mammoths and Paleodon, a large number of other diverse creatures, including woolly rhinoceroses, giant ground sloths, and glyptodons, went extinct. Our entire ecosystem may once again face another ecological crisis of large-scale animal extinction, or even a global mass extinction, but this time the crisis may be a catastrophic one for the entire proboscidean species. Asian and African elephants, though still existing on our planet, are also precariously endangered. After facing their last crisis 11 million years ago, their unparalleled molars and naturally formed trunks have exhausted their evolutionary potential—it's unimaginable that they could evolve new organs like their ancestors, thus possessing a miraculous power to reverse their fate. After 60 million years of arduous struggle, experiencing three major rises and falls in glory, proboscis elephants will eventually fade from the historical stage. Perhaps we need to accept the fact that in the universe, there is rise and fall, birth and death. Species, like life, have their own cycles. In the process of species evolution, there is a force that we cannot fully understand or control, quietly determining their life and death, just as we ourselves cannot control our own destiny. The past cannot be changed, and the future cannot be pursued, but the evolutionary story of elephants has already composed a magnificent and colorful dream of life and death, enough to remain in the long river of history and deep in the hearts of those who love nature.