The journal Nature published online the research findings of Wang Haibing and Wang Yuanqing from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Meng Jin from the American Museum of Natural History on the evolution of the middle ear in early mammals. Through reporting a new genus and species of Early Cretaceous multituberculate mammal, Jeholbaatar Kielanae, discovered in Lingyuan, Liaoning, a new model for the evolution of the middle ear in mammals was proposed.

The latest research published on mammal fossils discovered in  This fossil, from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Changzigou, Lingyuan, Liaoning Province, was preserved on the same rock slab as a Beipiao sturgeon fossil. After extensive and meticulous indoor restoration, data processing, and comparative studies, the research team determined that the fossil represents a new species of multituberculate mammal from the family Ephemeropterygii. It was named *Jeholus geysiensis*, with the genus name derived from the Jehol Biota. This is the first report of a multituberculate mammal fossil from the Jiufotang Formation. The species name is dedicated to Polish paleontologist Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska.

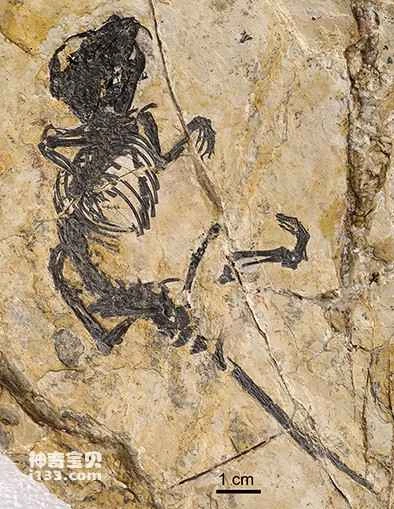

This fossil, from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Changzigou, Lingyuan, Liaoning Province, was preserved on the same rock slab as a Beipiao sturgeon fossil. After extensive and meticulous indoor restoration, data processing, and comparative studies, the research team determined that the fossil represents a new species of multituberculate mammal from the family Ephemeropterygii. It was named *Jeholus geysiensis*, with the genus name derived from the Jehol Biota. This is the first report of a multituberculate mammal fossil from the Jiufotang Formation. The species name is dedicated to Polish paleontologist Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska.

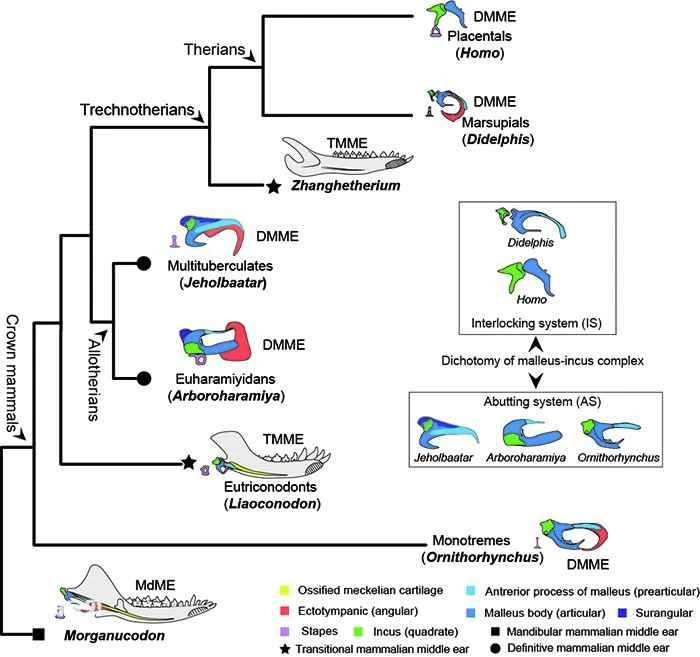

In the evolutionary history of vertebrates, the evolution of the mammalian middle ear is generally considered a classic case of biorecapitulation: the mammalian middle ear has undergone three evolutionary stages, from the mandibular Mammalian Middle Ear, the transitional Mammalian Middle Ear, to the definitive Mammalian Middle Ear. This has made related research one of the hot topics in early mammalian evolutionary studies, but the timing and mechanisms of different middle ear evolutionary stages in various mammalian lineages have always been challenging research points.

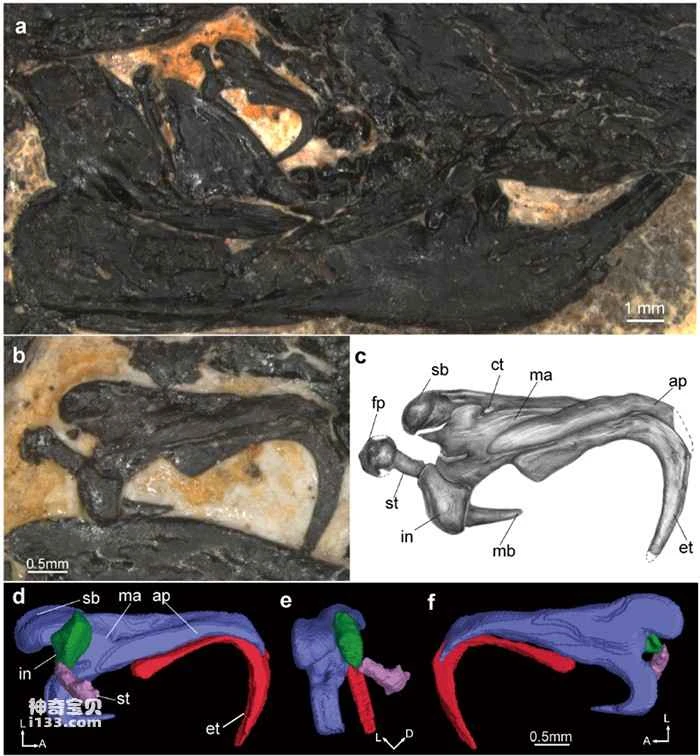

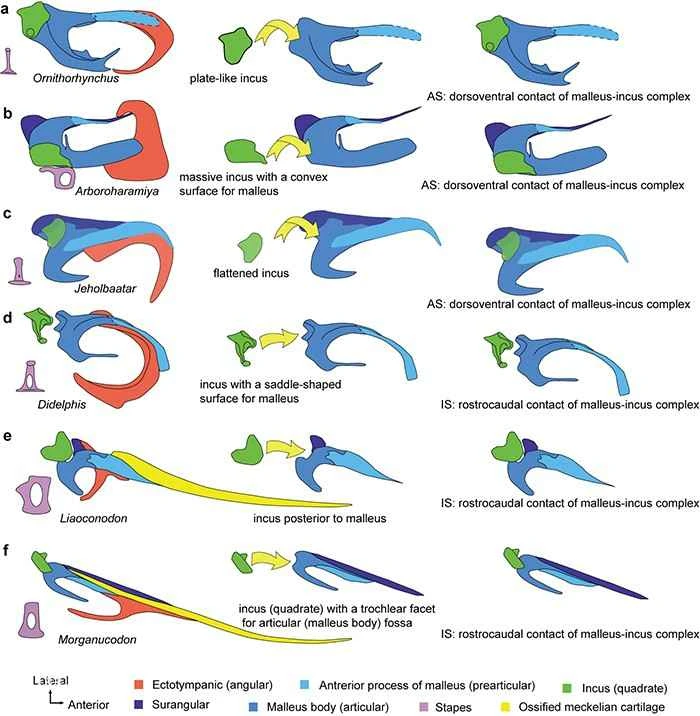

The holotype of *Jeholornis geysiensis* preserves a complete middle ear structure, providing direct evidence for the study of ear evolution in early mammals. This research reveals the complete morphology of the various bones in the middle ear of multituberculates, as well as their contact relationships, adding a significant piece to the puzzle of the evolutionary event of the postdentary bones in mammals from the mandibular middle ear to the typical mammalian middle ear. Based on this study, researchers have gained a clearer understanding of the evolution of the surangular bone in mammals. This study reveals for the first time that the surangular bone in early mammals evolved from a separate bone into a state of gradual fusion with the malleus body, becoming the posterolateral part of the malleus. The malleus and incus in the new specimen are morphologically complete, basically preserving the original joint state, and the two have an overlapping (dorsoventral) contact relationship. Researchers further propose that during the evolution of the mammalian middle ear, although the morphology of the middle ear bones changed greatly, the malleus-incus joint mode exhibited two patterns: overlapping joint and saddle joint.

Another significant breakthrough in this study lies in the researchers' proposal of a new model for the evolution of the middle ear in early mammals, based on morphological and phylogenetic analyses. Regarding the evolutionary mechanism from the mandibular middle ear to the typical mammalian middle ear, two common hypotheses are "cerebellar expansion" and "negative allometric growth." The "cerebellar expansion" hypothesis posits that the enlargement of the skull during mammalian growth leads to the posterior displacement of the middle ear, eventually detaching it from the mandible. The "negative allometric growth" hypothesis emphasizes that in early embryonic development, the middle ear skeleton is relatively larger than the mandible, and ossification occurs earlier; therefore, in later embryonic development, as the skull and mandible enlarge, the middle ear skeleton eventually detaches from the mandible. With advancements in fossil studies (eutrichodontids) and embryological studies of extant animals (monophrenia and marsupials), the support for these two hypotheses is steadily weakening. Another view suggests that the presence of ossified McBurney's cartilage and the eventual detachment of the postdentary bone may be related to mandibular function.

In their latest paper, researchers propose a new hypothesis regarding the evolutionary mechanism of the mammalian middle ear in *Euthyrodon* (a type of mammal with multiple tubercles and thieves), based on phylogenetic analysis. Among Mesozoic mammals, *Euthyrodon* had already evolved a typical mammalian middle ear by at least the Middle/Late Jurassic (approximately 160 million years ago); while during the same period, and even later in the Early Cretaceous, all other known mammalian groups retained transitional middle ears. Furthermore, *Euthyrodon* possesses a unique dentary-squamous jaw joint, which is relatively open and supports a wide range of anteroposterior mandibular movement, clearly distinguishing it morphologically and functionally from the hinged dentary-squamous jaw joints in mammals. Combining the currently known morphology of the *Euthyrodon* middle ear and the differentiation time of the dentary-squamous jaw joint, the researchers propose that in the evolution of the mammalian middle ear, the malleus-incus joint (primitive jaw joint) and the dentary-squamous jaw joint (secondary jaw joint) co-evolved, with the overlapping primitive jaw joint reducing the spatial constraints on the middle ear skeleton. Researchers have proposed that there was also a transitional middle ear evolutionary stage in therapsids, but this stage likely lasted for a shorter period than in any other mammalian group. The evolutionary mechanism is likely that the unique dentary-squamoclit joint and feeding method of therapsids provided more significant selective pressure for the middle ear to separate from the mandible than in other groups, thus accelerating the evolution of the middle ear. As a result, therapsids evolved a typical mammalian middle ear at least 160 million years ago (earlier than any other mammalian group).

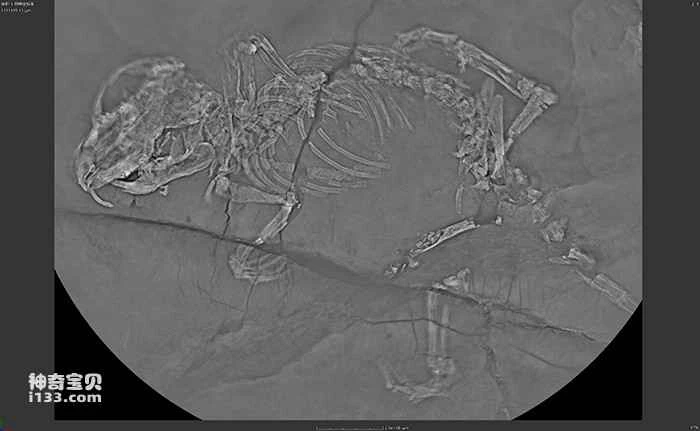

The three-dimensional scanning of the fossils in this study was completed at the High-Precision CT Scanning Center of the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, Chinese Academy of Sciences, using "160-Micro-Computed Laminography" to perform high-precision scanning of the fossils.

This research was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Category B), the Basic Science Center Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Craton Destruction and Terrestrial Biological Evolution), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Youth Fund), and the Open Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Modern Paleontology and Stratigraphy.

Article link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1792-0

Figure 1. The holotype specimen of *Jeholometabolum* (lower right corner) and a specimen of *Sturgeon beipiaoense* are preserved on the same rock slab (Photo provided by Wang Haibing)

Figure 2. Homotype of *Jeholometaeus geysiensis* (Photo provided by Wang Haibing)

Figure 3. The shape of the left middle ear of the Jehol Junshou (Photo provided by Wang Haibing)

Figure 4. Two articulation modes of the malleus-incus in the evolution of the mammalian middle ear (Image provided by Wang Haibing)

Figure 5. Evolutionary history of the middle ear in early mammals (Image provided by Wang Haibing)

Figure 6. CL scan image of the holotype specimen of Jeholornis geysiensis (Image provided by Wang Haibing)

Figure 7. Ecological restoration map of the Rehe Junma (Photo provided by Xu Yong)