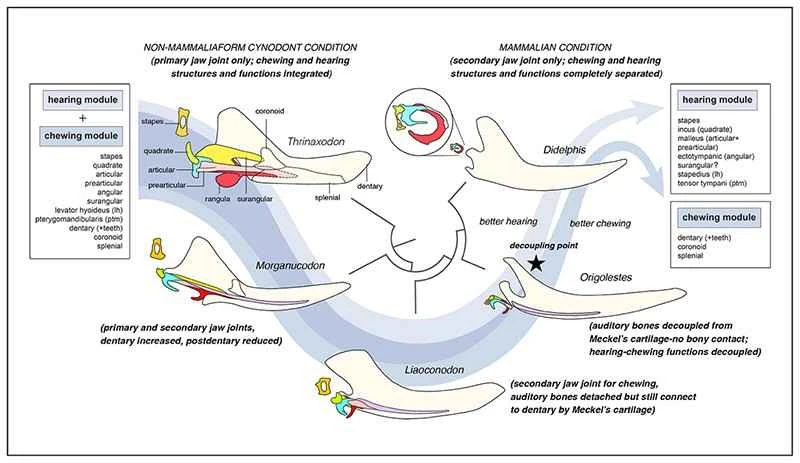

On December 5, 2019, the journal *Science* published online the research findings of Mao Fangyuan and Wang Yuanqing from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Meng Jin from the American Museum of Natural History, among other scholars, on the Early Cretaceous basal mammal *Liyiyuan*. The findings revealed that in the evolution of hypoporous vertebrates, the once integrated auditory and chewing structures, regulated by their respective genetic mechanisms, adapted to natural selection in mammals to improve the efficiency of hearing and chewing, exhibiting a modular divergent evolution. *Liyiyuan* perfectly demonstrates the phenotypic characteristics of the divergence points between these two modules in basal mammals. The separated auditory and chewing modules enhanced their variability or evolutionary capacity, becoming one of the possible intrinsic driving factors for the radiation evolution of mammals.

Modular evolution is a concept combining evolutionary biology and developmental biology. Organisms can be broken down into small morphological, developmental, or functional units at different levels; these units are relatively independent in development and gene regulation, and can exhibit different rates of variation during evolution; they also possess conservation, typically allowing them to independently undergo natural selection without affecting the morphology and function of other modules. The forelimbs of vertebrates are an example of homologous modular evolution, evolving into wings, fins, or even human hands, without affecting the morphology and function of other parts, such as the hindlimbs. Researchers have proposed that the mammalian mandible and auditory ossicles are a special example of modular evolution. Their uniqueness lies in the combination of homologous module diversity and functional specialization, and the gradual evolution from a complex structure integrating morphology and function into two completely independent organ modules.

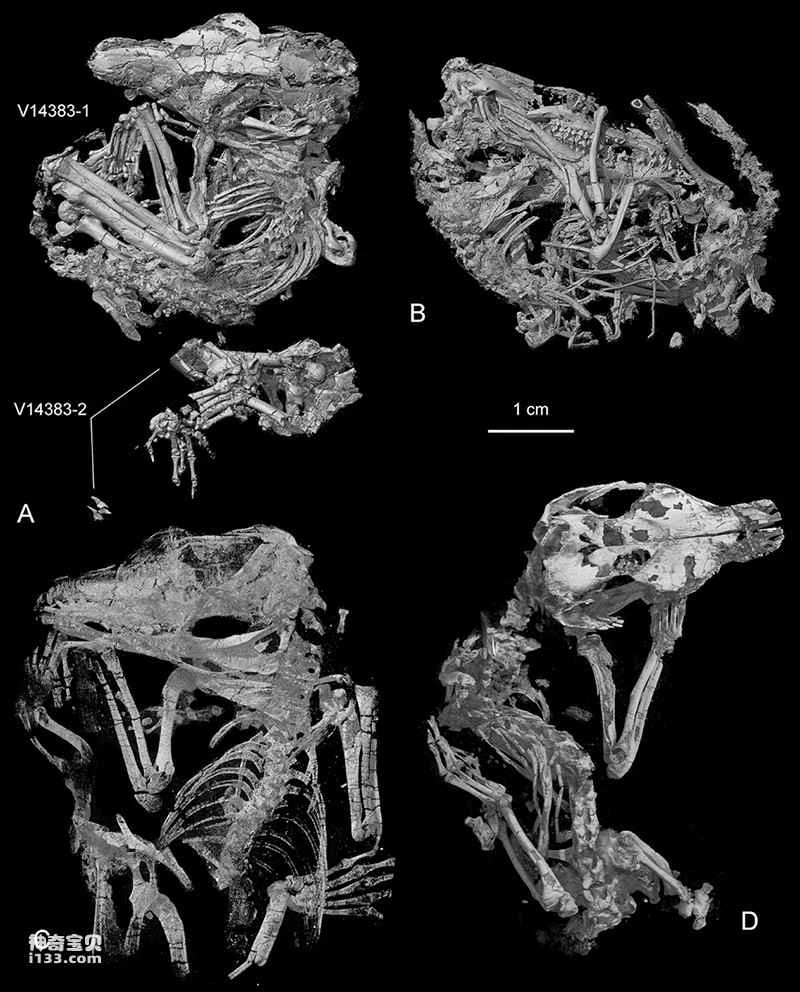

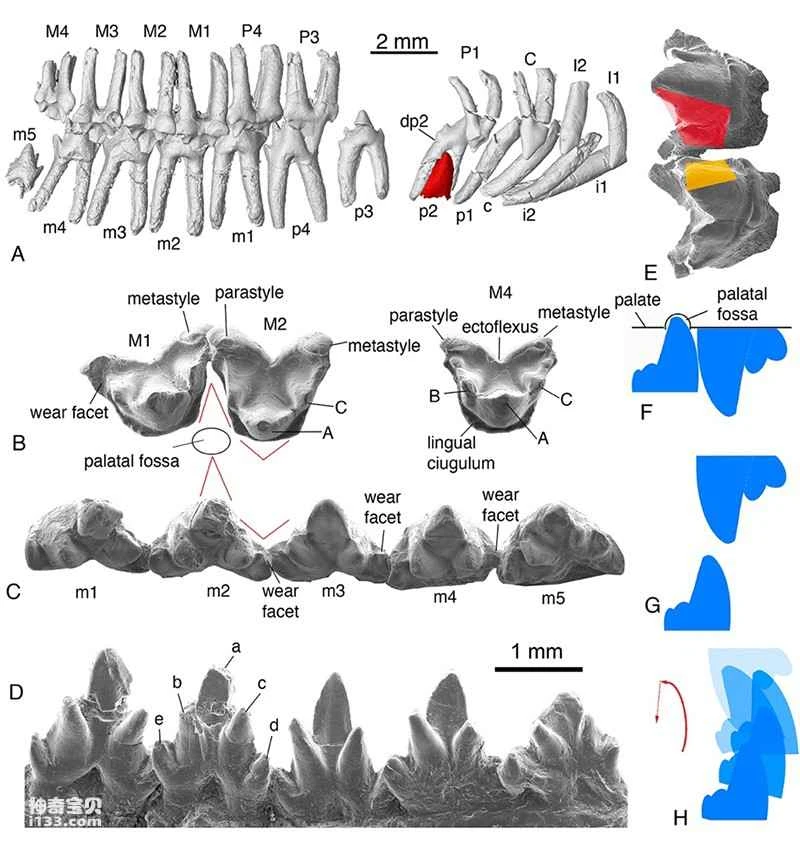

Researchers, using six three-dimensionally preserved specimens from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota (Lujiatun Formation), employed micro-computed tomography (CT) and three-dimensional reconstruction to establish a new genus and species of toothed mammal: *Li's Protozoan*, commemorating Li Chuan-kui, one of the authors of the memorial article and a pioneer in early mammalian research in China who passed away this October. The researchers believe that the burial morphology of the specimens indicates that these animals died in a resting state, and the fossils were largely undisturbed. The paired specimens may reflect some form of social behavior in basal mammals. Evidence from the dentition, jawbones, and wear marks of *Li's Protozoan* within the same genus and individual suggests that during chewing, the mandible exhibited not only opening and closing movements but also lateral movement and rotation along its long axis. This multidirectional movement of the mandible during chewing is likely one of the selective pressures leading to the separation of the auditory ossicles from the dentary and McBurney's cartilage in mammals.

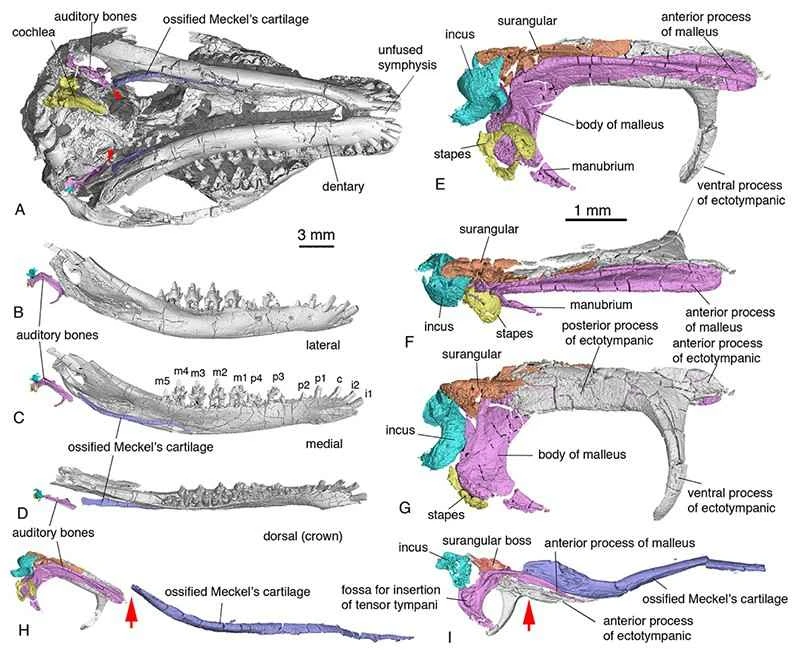

Extensive research in morphology, anatomy, developmental biology, and genetics has long established a homologous relationship between the auditory ossicles (malleus, incus, and ectymoidus) of mammals and the postdentary bones (articular bones, prearticular bones, quadrate bones, and angular bones) of reptiles. Recent studies have further demonstrated that these bones are regulated by the same genetic mechanisms during the early development of various groups; these mechanisms can even be traced back to the development of the mandible in fish. In the past two decades, discoveries of Mesozoic mammals in western Liaoning, China, including the ossified McBurney's cartilage of reptiles and the auditory ossicles of Liaoning Conodonts, have provided evidence of an evolutionary transitional pattern from the mandibular middle ear to the typical mammalian middle ear. However, in the transitional middle ear, although the auditory ossicles are detached from the dentary, they remain tightly intertwined with the ossified McBurney's cartilage, which is connected to the dentary; therefore, the functions of hearing and chewing are not completely separated and still influence each other. Multiple specimens of *Lisbeckia orientalis* for the first time demonstrate a key feature: the absence of bony connection between the ossicles and McBurney's cartilage. This represents a crucial juncture in the separation of the auditory and masticatory modules in mammalian evolution, bridging the phenotypic gap between transitional and typical mammalian middle ears. In terms of phylogeny and phenotypic evolution, it represents a more advanced evolutionary stage among basal mammals. The establishment of this separation phenotype provides evolutionary time and phenotypic reference and verification for models and hypotheses concerning the evolution of the mammalian middle ear (such as the developmental biology theory that the final separation of the ossicles from the mandible in early mammalian ontogeny is due to the fracture of McBurney's cartilage). From a morphological and functional perspective, the separation of the auditory and masticatory modules eliminates the physical constraints that would prevent mutual interference between them, increasing the possibility of evolution and multidirectional adaptation for both modules. The auditory organs possess the potential to develop towards high-sensitivity, high-frequency hearing, while the masticatory organs gain the possibility of diverse evolution of teeth and occlusion to ingest different foods.

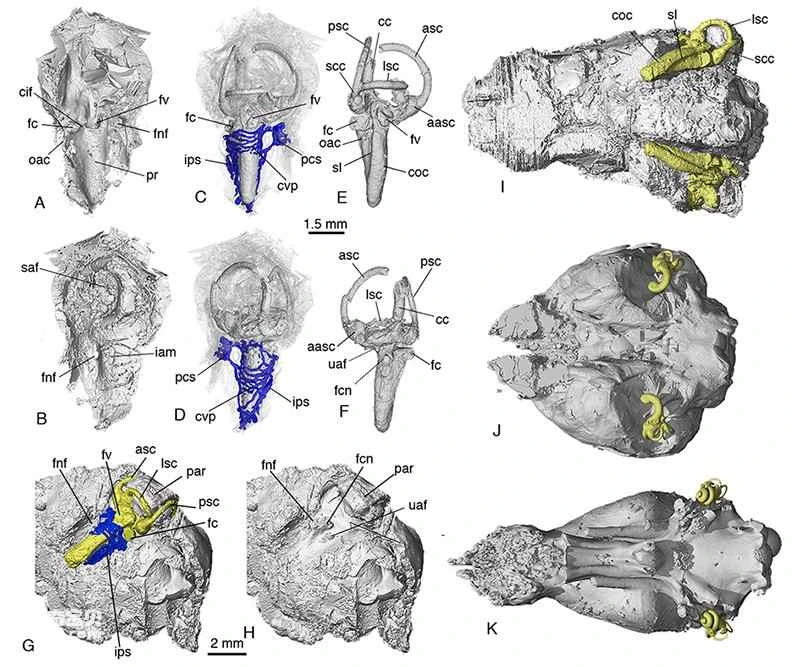

Thanks to the results of high-precision CT scans, *Triconodontia lijiri* also exhibits nearly complete morphological features of the auditory ossicles, a characteristic found in basal mammals (and even in all known Mesozoic mammals), providing credible fossil evidence for further in-depth research into the evolution of mammalian auditory ossicles. Particularly noteworthy is that, in addition to the stapes, malleus, ectotympanum, and incus found in all mammals, *Triconodontia lijiri* also retains the supraorbital bone. Since studies of the auditory ossicles of *Triconodontia* and *Arboretus ahoi* suggested the possibility of a supraorbital bone, increasing evidence suggests that the supraorbital bone entered the middle ear during early mammalian evolution. *Triconodontia lijiri* provides the most credible three-dimensional evidence of a supraorbital bone to date. In basal types of the Triconodontia-therapeutic lineage, the supraorbital bone is a plate-like structure, with its anterior projection remaining between the ectotympanum and malleus, and its posterior portion forming an anterior-posterior joint with the incus along with the malleus. The presence of the superior ossicle in basal mammals presents a challenge to paleomammalian research and modern developmental biology: was this ossicle directly lost during mammalian evolution, or how did it fuse with another part, resulting in the absence of the superior ossicle in the middle ear of extant species? Further fossil discoveries and more detailed developmental biological studies may answer this question. The inner ear, closely related to the middle ear ossicles and an important part of the auditory organ, also exhibits a unique evolutionary structure in the Triconodonts-theriformes lineage. Compared to extant mammals and monotremes, this lineage features a cochlear duct with secondary bony plates that extends linearly towards the middle of the skull base, with a rich network of reticular veins around the cochlea. The length and width of the cochlear duct in *Lisbeckia orientalis* even reach the limits of the petrous bone, and its volume is proportionally larger than the cranium, almost reaching its limit. This can be considered an evolutionary "experiment" of different elongation patterns in mammalian cochleas; to some extent, it supports the spiral structure of the theriform cochlea, representing a more feasible adaptive evolutionary direction for extending the cochlear duct within the limited space of the petrous bone. In any case, basal mammals (including humans) have enhanced their variability or evolutionary capacity through various experiments, and have ultimately succeeded in becoming one of the dominant players in Earth's ecosystem.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Category B), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Special thanks are extended to the Chaoyang Jizantang Museum for its generous support.

Original link: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/early/2019/12/04/science.aay9220

Figure 1. CT-reconstruction of the Origolestes lii pattern (Image provided by Mao Fangyuan)

Figure 2. Tooth morphology, wear details, and occlusal movement relationships of *Origolestes lii* (Image provided by Mao Fangyuan)

Figure 3. Morphology and anatomical location of the middle ear, inner ear, and McBurney's cartilage in *Lissaurus*. H, arrow points to the point of separation between the ossicles and McBurney's cartilage. I, arrow points to the bony connection between the ossicles and McBurney's cartilage in the transitional middle ear of *Lyoconodon* (Image provided by Mao Fangyuan).

Figure 4. The structure of the inner ear and the morphology and relative relationship of the brain cavity in *Li's Protozoan* (AI), and a comparison with monotremes (J) and marsupials (K). Yellow represents the inner ear structure's endothelial model, and blue represents the inner ear's related vascular system (Image provided by Mao Fangyuan).

Figure 5. Schematic diagram of the evolutionary separation of auditory and mastication morphological functions in mammals (the herbivores) (Image provided by Mao Fangyuan)

Figure 6. Ecological environment of the Li's Source predator and reconstruction of the Lujiatun fauna (drawn by Zhao Chuang)