Recently, Wang Min, Zhou Zhonghe, and Thomas from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, published their latest research findings in the *Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences* (PNAS), reporting the discovery of an Early Cretaceous primitive bird in China: *Jinguofortis perplexus*. The discovery of *Jinguofortis perplexus* provides a wealth of crucial information for discussing early avian evolution and ecological differentiation, demonstrating that developmental plasticity played a very important role in the early stages of avian evolution.

The bird *Jinguobird* was discovered in the Early Cretaceous Dabeigou Formation of Hebei Province. In 2017, a research team led by Zhou Zhonghe conducted fieldwork at the site and collected samples from the overlying volcanic ash. Researcher Meng Qingren of the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, used SIMS zircon U-Pb dating to determine that *Jinguobird* lived approximately 127 million years ago. The research team conducted comparative morphological, histological, flight, and phylogenetic studies on *Jinguobird*, concluding that it belongs to the most primitive pygomorphic birds known to date, second only to Confuciusornis. Pygomorphs are birds whose terminal caudal vertebrae fuse into a single composite bone (called the pygomorph), encompassing all birds except *Archaeopteryx* and *Jeholornis*. Enantiornithes and Neornithoids (the latter evolving into all modern birds) were the most evolutionarily successful birds of the Mesozoic Era, with early members of these two groups exhibiting numerous advanced morphological and physiological characteristics and a large number of genera and species. However, the more primitive pygomorphic genera and species are very rare, consisting only of *Confuciusornis* and *Huaornis*. This created an "evolutionary gap" between the most primitive long-tailed birds (Archaeopteryx, Jeholornis) and the more advanced enantiornithines and ornithoids, greatly limiting our understanding of the early evolution of pygomorphs. *Jinguoornis* fills this gap, exhibiting a highly mosaicized combination of evolutionary features: its dentition, parts of its skull, and shoulder girdle morphology resemble those of non-avian theropod dinosaurs, but it also possesses typical avian features such as vestigial fingers, elongated forelimbs, and a fused pygomorph, which is the origin of its species name. Its genus name is derived from the pinyin of "巾帼" (Jinguo), dedicated to all female researchers working on the front lines.

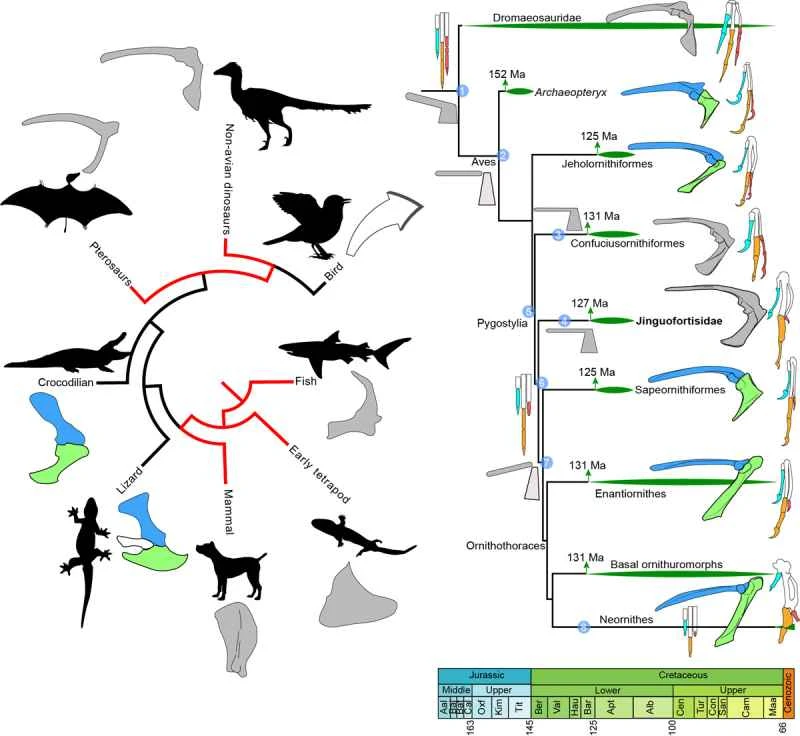

The *Jinguofortis* is morphologically similar to the *Chongmingia*, reported in a 2016 study. *Chongmingia* is incompletely preserved, particularly lacking its caudal vertebrae and skull, making its systematic position difficult to determine in its initial studies. The discovery of *Jinguofortis*, however, provides clues to resolving the taxonomic position of *Chongmingia*: studies of numerous Mesozoic bird phylogenies indicate that *Jinguofortis* and *Chongmingia* form a sister group, belonging to the most primitive pygostyle group known outside of Confuciusornis. The research team named this lineage Jinguofortisidae. The most distinctive feature of Jinguofortisidae is the fused coracoid and scapular bones (called the scapular coracoid), a phenomenon found only in Confuciusornis in Mesozoic birds and primarily in Paleognathea (ostriches, emus, etc.) in extant birds. In most birds capable of flight, these two bones are independent. The fused coracoid bone is a very primitive feature, predating even the appearance of phalanges (toes) in the evolutionary history of tetrapods. The separation of the two bones began in primitive amniotes and subsequently spread widely (such as in squamosines and crocodiles). However, some groups, including most non-avian dinosaurs and pterosaurs, independently evolved fused coracoid bones. The scapula and coracoid bone often show a tendency to fuse during development, primarily due to their origin as undifferentiated homogeneous aggregates in the early stages of development. Separation of these two bones only occurs during chondrogenesis when osteogenic processes or preosteoblast differentiation are delayed.

By tracing the development of these two bones in major tetrapod groups, the research team proposed that the fused scapular coracoid occurred independently in Confuciusornis and Georgornis, and that the fusion may stem from the relatively rapid osteogenic process during individual development in these two groups. Analysis of the bone tissue structure of primitive birds also supports this hypothesis. Georgornis and Confuciusornis grew faster than Archaeopteryx and Jeholornis. This faster growth rate shortened the time required to reach adulthood, reducing the chance of predation. However, the accelerated osteogenic process also caused the scapula and coracoid to separate "before" they could ossify, resulting in a fused scapular coracoid (which can be seen as a "side effect" of accelerated ossification). In contrast, more advanced birds, primitive ornithomorphs, and enantiornithines had slower growth rates. Early representatives of ornithoids and enantiornithines were significantly smaller than *Eriocheir sinensis*, so their slower growth rate did not significantly prolong the time required to reach adulthood. These two groups already possessed skeletal-muscle systems similar to modern birds. During embryonic development, different muscles exerted different effects on the still-cartilaginous scapula and coracoid bones, facilitating their separation during ossification. The research team proposed that the scapula and coracoid bones in *Eriocheir sinensis* and *Confuciusornis* may have originated from hypermorphogenesis during heterochronic development (due to rapid growth, offspring exhibited ancestral characteristics in early development, and further developed new features based on these characteristics), reflecting developmental plasticity. Developmental plasticity refers to the ability of an organism to alter its developmental process when the environment changes, often inducing new traits. These findings further indicate that developmental plasticity is a crucial factor when discussing the early evolution of birds or other organisms (especially mosaic evolution).

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Excellent Young Scientists Fund), the Basic Science Center Project, and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Figure 1. Homotype of the questionable bird, LSF imaging of the skull, bone tissue structure, and wing loading-aspect ratio distribution of the primitive bird (Image provided by Wang Min).

Figure 2. Simplified evolutionary diagram of the scapula-coracoid bone in major vertebrate groups; Mesozoic avian phylogeny reveals important evolutionary stages of the pectoral girdle and hand bones (Image provided by Wang Min).

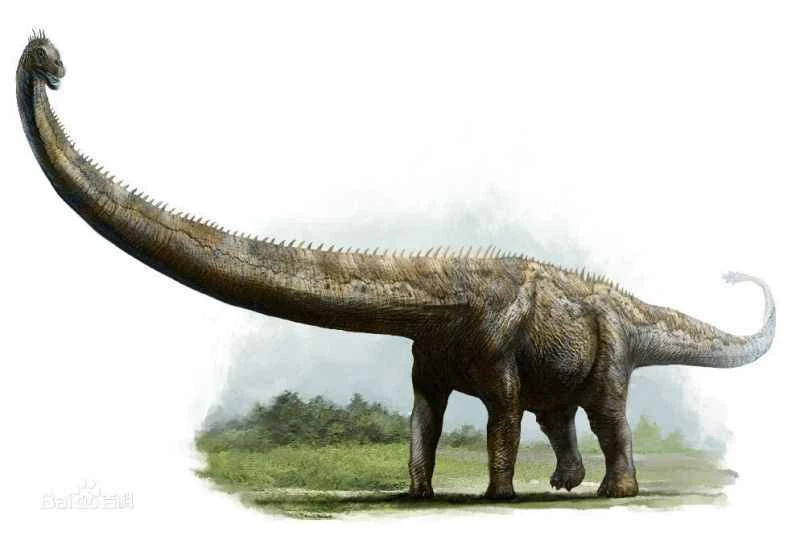

Figure 3. Reconstruction of the puzzled female bird (drawn by Zhang Zongda)