When interpreting and reconstructing incomplete or oddly shaped bilaterally symmetrical animal fossils, their dorsal or even anteroposterior axes are sometimes reversed. Such cases are numerous throughout the history of paleontology, such as *Elasmosaurus platyurus* and *Hallucigenia*. Recently, Zhu Min, Zhu Youan, and Lu Jing of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, published their latest research on a Silurian jawed fish, *Silurolepis platydorsalis*, in the journal *Royal Society Open Science*. This research proves that the specimen's previous descriptions were also reversed, and that *Silurolepis platydorsalis*, previously classified as a placoderm, is actually a Silurian placoderm endemic to my country. This discovery is significant for tracing the earliest evolution of jawed vertebrates.

Fossils of jawed fish from the Silurian period are extremely rare. In the 1970s, Chinese scholars discovered a relatively complete rectangular fish carapace fossil in the Silurian strata of Qujing, Yunnan, and named it *Siluriomyx latifolius*. In 2010, based on characteristics such as the rectangular carapace and the presence of two median dorsal plates, *Siluriomyx latifolius* was reclassified as an antiarch. Antiarchs are a large group of placoderms and one of the representative fossils of the Devonian "Age of Fishes." Edward D. Cope, who reversed the front and back of a *Plateaurus* fossil, once mistook the antiarch fossil for a prehistoric sea squirt, and named it "antiarch" to distinguish it from modern sea squirts; the name has been used ever since.

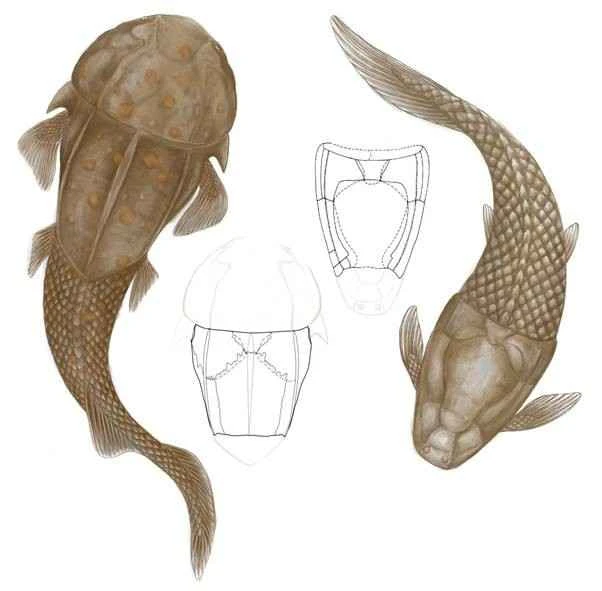

In the past decade, a large number of well-preserved early jawed fish have been discovered in the Silurian strata of Qujing. Among them, the discovery of *Qilinyu rostrata* demonstrates the great morphological diversity of early jawed fish, and the rectangular carapace with multiple mid-dorsal plates was no longer exclusive to armored fish. This has prompted researchers to re-examine Silurian fossils. After careful observation and further meticulous repair, the structure of the joint with the head carapace was exposed at the "posterior edge" of the carapace of *Qilinyu rostrata*. This means that this is actually the anterior edge of the carapace, and the specimen was reversed in previous studies. The corrected carapace bone pattern and head-neck joint morphology prove that the *Qilinyu rostrata* fossil actually belongs to a jawed fish closely related to *Qilinyu rostrata*, which has only been found in Silurian strata in China so far, namely maxillate placoderms. This group also includes the well-known Entelognathus primordialis.

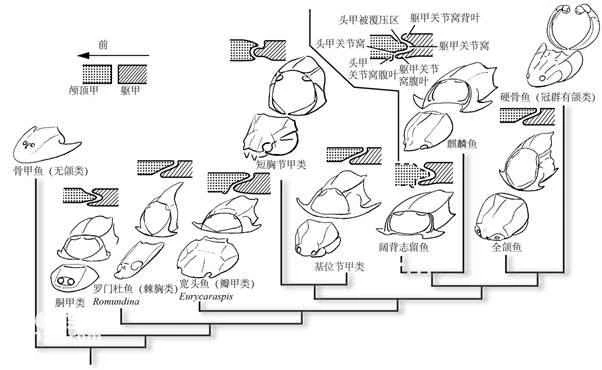

Building upon the new discovery of placoderms, this study clarifies the characteristic evolution of exoskeletal head-neck joints in the earliest jawed vertebrates. While most jawed vertebrates exhibit varying degrees of mobility between their head and trunk, the exoskeleton's head-neck joint—the joint between the cranial carapace and the trochanteric/membranous pectoral girdle—is only found in early jawed vertebrates with well-developed membranous bony plates. Traditionally, exoskeletal neck joints have been classified into broad categories such as "gliding joints," "flexor joints," and "reverse flexor joints." This study, for the first time, provides a detailed analysis of the numerous independent anatomical features included in these categories. The results show that Silurian placoderms such as *Qilinus* and *Silurios* possess exoskeletal head-neck joints that incorporate features from different categories, making them unclassifiable. Furthermore, the previously defined categories do not have absolute boundaries and can actually transform into each other through stepwise evolution.

Placing these features within the currently popular framework of early jawed vertebrate evolution reveals that the exoskeleton head-neck joint underwent multiple parallel and reverse evolutions. This suggests that as research into other complex anatomical structures deepens, the distribution of features, including the head-neck joint, may support different hypotheses regarding the evolution of the earliest jawed vertebrate systems.

The discovery and detailed study of a series of important early jawed vertebrates from the Silurian and Early Devonian periods reveal that the origin of the jaw and the earliest evolution of jawed vertebrates are highly complex, and no single theoretical framework can currently integrate all the conflicting evidence. Only by continuing in-depth comparative anatomical studies on more fossil genera and species can we provide crucial empirical evidence for the precise morphology of jawed vertebrates in the earliest stages of the vertebrate evolutionary tree.

This research was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Paper link: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.191181

Figure 1. *Silus latifolius* was previously reconstructed as a placoderm by reversing its front and back (right, line drawing from Zhang Guorui et al., 2010). Based on new evidence, it has now been reconstructed as a placoderm with a full jaw (left, line drawing and reconstruction). (Illustration by Yang Hongyu)

Figure 2. Exploded and cross-sectional diagrams of the exoskeleton head-neck joint in early jawed vertebrates, showing the characteristic evolution of the exoskeleton head-neck joint. Within the current phylogenetic framework of early jawed vertebrates, the morphology of the exoskeleton head-neck joint has undergone multiple parallel and reverse evolutions, implying that the evolutionary framework of this system may have undergone significant changes.