In June 1995, the American Museum of Natural History reopened two dinosaur galleries to the public after three years of renovations. The revamped exhibitions immediately attracted significant public attention. The new displays not only made the dinosaurs more lifelike but also reflected the latest findings in dinosaur and phylogenetic studies. The previous chronologically arranged exhibits of early and late dinosaurs were replaced by galleries dedicated to saurischians and ornithischians, organized using cladistic research, allowing visitors to understand the dinosaur lineage. This was the first large-scale dinosaur exhibition in the museum world to be presented using cladistics—the best scientific method for establishing biological phylogenetic relationships.

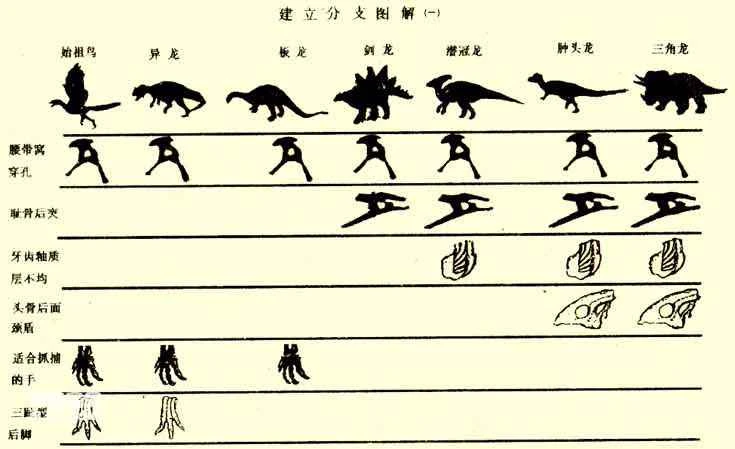

Dinosaur Branch Diagram (Part 1)

Cladoscopy, also known as phylogenetic systematics, is a method for determining the phylogenetic relationships among various organisms. The concept of cladistics was first proposed by the German entomologist Hennig in the 1950s. In the late 1960s, the American Museum of Natural History, under the leadership of Dr. Nils Nilsson, became a center for the further development and practice of this new scientific method. Since then, cladistics has gradually become dominant in the study of biological evolutionary relationships, profoundly influencing paleontologists worldwide in their efforts to study a range of complex issues, from the origins of birds to zoogeographical distribution. The American Museum of Natural History's placement of its dinosaur exhibits within the context of cladistics fully represents the research focus of the museum's scientists.

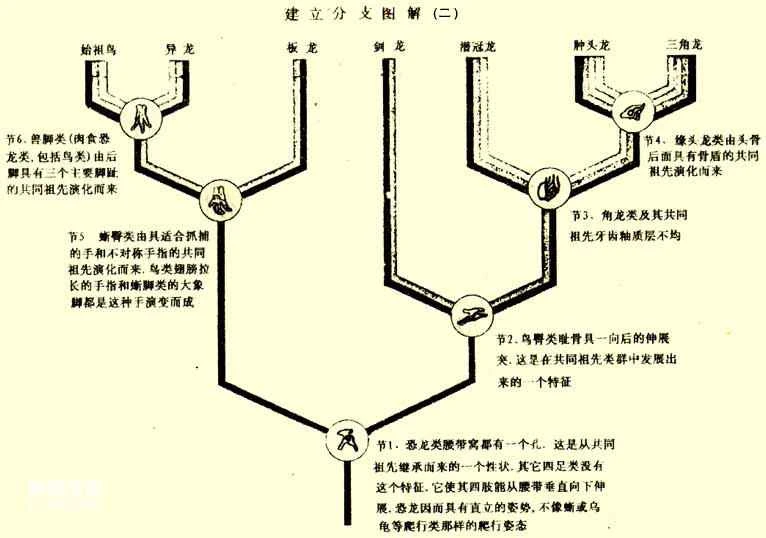

Dinosaur Branch Diagram (Part Two)

The difference between cladistics and traditional methods for reconstructing biological systems is that it uses the phenotypic distribution of common ancestral traits to examine systemic relationships. Scientists primarily look for similar patterns of traits exhibited in different animals. This phenotypic distribution typically groups closely related groups into a hierarchy, with smaller groups contained within larger ones. For example, the "dinosaur" group is contained within the larger "vertebrates" group because dinosaurs and all other vertebrates have vertebrae. The vertebrae are referred to as a common ancestral trait for the vertebrate group. Each group or clade is defined by a series of such common ancestral traits inherited from a common ancestor.

While cladistics is not yet a perfect method and still needs criticism and testing, it is a more reliable and objective approach to determining kinship than relying on fossil age or specific rock strata. For example, cladistic analysis suggests that birds originated from a small, likely carnivorous dinosaur, such as *Deinonychus* or *Mexicanraptor*. These carnivorous emuosaurs lived during the Cretaceous period, 107 to 72 million years ago. However, the earliest bird currently recognized—*Archaeopteryx*—lived approximately 140 million years ago in the Late Jurassic period. Based solely on geological time, scientists might arrive at a conclusion that contradicts objective reality: the earliest birds evolved into dinosaurs like *Deinonychus* and *Mexicanraptor*. How then can this contradiction be resolved? Cladophysical explanations suggest that the fossil record may be incomplete; perhaps a more ancient animal, very similar to *Deinonychus*, evolved into both birds and the later emuosaurs (including *Deinonychus* and *Mexicanraptor*), but fossils of this ancient ancestor have not yet been discovered.

By using cladistic analysis of trait combinations, scientists can examine phylogenetic relationships or lineage trees, not to identify ancestors and descendants, but simply to hypothesize the closest kinship among animals. When reliable phylogenetic results cannot be obtained from the geological age of fossils, cladistic analysis provides important background information on the possible locational relationships within animal phylogenetic structures. With cladistics, scientists have a more realistic and objective understanding of where evolutionary branches exist within geological timeframes and where "missing links" in the fossil record exist within these branches.

In the new dinosaur exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History, scientists selected several of the most representative genera from various dinosaur types to create phylogenetic charts. The choice of shape is crucial in this analysis. For extant animals, traits can be selected from various perspectives, including genetics, biochemistry, and even behavior. However, for fossils, selection is limited to traits specific to skeletal structure. Therefore, paleontologists often face greater constraints in trait selection. Many traits with overly limited distributions are meaningless. For example, "deck" only appears in one of the representative species in this phylogenetic chart, Stegosaurus, thus providing no clues about kinship for these specific dinosaurs. Similarly, the trait "limbs" is present in all dinosaurs and many other animals, making it too general and also meaningless. Using a relatively limited distribution to select traits often significantly reduces the number of potentially useful shapes.

For simplicity and ease of understanding, this branch diagram only shows 6 traits. In actual scientific research, scientists often use 20 to 100 traits to explore the kinship between organisms.

By carefully comparing skeletons and charting trait distributions, it is possible to identify patterns of traits that repeatedly form the same group. Large amounts of data must be processed using computer programs. In each study, every discrepancy in trait distribution requires researchers to re-examine specimens and consider issues such as the adequacy of specimen preservation, whether the traits are truly identical or merely superficially similar. Then, the phylogenetic system is visually depicted in the clade diagram. The clade diagram supported by the largest number of trait groups is selected as the optimal clade diagram, but it only serves as a basis for further research, not as an immutable final conclusion. Science is endless; the emergence of new theories often renders many old ones obsolete, while previously disregarded hypotheses are re-adopted. However, all these processes must withstand the test of science and practice. Even the clade diagrams displayed at the American Museum of Natural History may only be temporary optimal clade diagrams.

In cladistic analysis, traits that define larger groups are considered primitive because they appeared earlier, while traits common to smaller groups are called advanced or derived traits because they appeared later. In this approach, the concepts of primitive and advanced are relative and do not imply that some traits are superior to others. In the example cladistic diagram, "perforated pelvic girdle" defines the group "Dinosauria," which includes all dinosaurs and birds. While "perforated pelvic girdle" is unique to dinosaurs among all vertebrates, it can be considered advanced relative to other vertebrates. However, when studying subgroups within the dinosaur family, this trait is considered primitive. Similarly, the four dinosaur genera constituting the Ornithischia group are defined by a derived shape called a "posterior pubic process," which, within Ornithischia, is considered relatively primitive due to its early appearance.

Today, many scientists' interest in dinosaurs has shifted towards studying their unique lifestyles and habits, rather than relying on intractable evidence. Although cladistic conclusions are frequently revised due to the constant discovery of new fossils, it is precisely through this process that scientists gain a more nuanced understanding of the phylogenetic relationships among organisms. Therefore, cladistics can be considered an objective and effective method for examining evolutionary pathways. The American Museum of Natural History boasts one of the world's most diverse collections of dinosaur fossils, and its cladistic-guided display allows visitors to gain a more objective understanding of the knowledge derived from the fossils themselves.