Since the first panda was discovered, over a century of joint efforts by Chinese and foreign scholars have led to continuous discoveries and an ever-growing panda family. To date, the family has been passed down through six generations.

I. The First Panda

The discovery of the first panda was a major event in the history of pandas. It not only proved that the ancestors of pandas were in China, but also pushed back the evolutionary history of pandas by nearly 1 million years.

The panda is so amazing, so how was it discovered?

The discovery of the Lufeng Ape (Ailurarctos lufengensis)

In the 1970s, coal miners in the Lufeng Basin of Yunnan Province discovered a large number of vertebrate fossils while working in a lignite mine in Shihuiba Village, 9 kilometers from Lufeng County. Upon learning of this discovery, the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences sent personnel to investigate in 1978. With the assistance of the coal miners, the researchers found animal fossils within the coal seams. Furthermore, they collected fossils of ancient apes from the coal seams. Due to the significant nature of this discovery, the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has conducted excavations at the fossil site for many years since 1978, obtaining a large number of vertebrate fossils. Particularly noteworthy are the discovery of ancient ape skulls, mandibles, limb bones, and some rare mammal fossils, including the Lufeng ape.

The stratigraphic position of *Ailuropoda lumens* fossils in Lufeng and their distribution in cross-sections.

In 1989, Wu Rukang et al. provided a detailed description of the stratigraphy and lithology of the Lufeng fossil site, from top to bottom as follows:

(8) Purplish-red, orange-red, and yellowish-brown sandy clay, 0.8m thick.

(7) Grayish-white and bluish-gray clay, 1.6m thick.

(6) Thin-layer lignite, 0.5m thick

(5) A layer of fine gray sand containing fossils of the early panda, 1.5-2.5m thick.

(4) Thin layers of black carbonaceous clay and gray fine sand, alternating layers, with a thickness of 0.2-1.8m.

(3) Dark brown blocky lignite seams containing fossils of *Ailuropoda melanogaster*, with a thickness of 0.3-1.4 m.

(2) Interlayered layers of dark brown carbonaceous clay and gray fine sand, containing fossils of *Ailuropoda spp.*, with a thickness of 0.7-3 m.

(1) Yellow sandy clay, 0.5-2m thick

In various excavations, the fossils of *Ailuropoda* unearthed in the above-mentioned sections include the following materials: 2 pieces from layer (2), consisting of the lower left fourth premolar and the lower left third molar; 12 pieces from layer (3), consisting of the upper left second premolar, upper left third premolar, upper left fourth premolar, upper left first molar, upper left second molar; upper right fourth premolar, upper right first molar, upper right second molar, lower right first molar, and lower right second molar; and 1 piece from layer (5), consisting of the upper right second molar.

The location of Lufeng panda

There's an interesting anecdote about the identification of the Lufeng Ape: In the early 1980s, Ms. Qi Guoqin of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, identified several bear fossils as *Ursavus depereti* when describing mammal fossils from Lufeng, Yunnan. Her article was published in *Acta Anthropologica Sinica*, Volume 3, Issue 1 and Volume 4, Issue 1. At that time, I was researching the origin and evolution of pandas and was quite interested in *Ursavus depereti*, so I consulted her and borrowed a specimen for further observation and comparison. I later discovered that the anatomical morphology of *Ursavus depereti*'s teeth, especially the upper fourth premolar and lower first molar, was very similar to that of similar panda specimens. When I returned the specimen, I also shared my observations about *Ursavus depereti* with her. At the same time, I informed her that similar panda fossils from Lufeng had also been discovered in the Yuanmou Basin of Yunnan.

Perhaps Ms. Qi had already considered further research on the ancestral bear of the Di family.

Their research (by Qiu Zhanxiang and Qi Guoqin) found that the length of the premolars to molars in the Lufeng specimen was about two-thirds that of the modern panda, indicating a smaller individual. The morphology of the premolars in the Lufeng specimen was similar to that of the panda, while the morphology of the molars was closer to that of the ancestral bear. The upper fourth premolar in the Lufeng specimen had three roots, a prominent cusp on the occlusal surface, and the middle one was slightly larger and higher. The length of the molars was slightly greater than the width, and there were strongly developed enamel folds on the tooth surface. The molars of the modern panda were wider than long, and the enamel folds on the tooth surface had evolved into protrusions or ridges of varying sizes. They believed that this animal was intermediate in morphological characteristics and phylogenetic relationships between the ancestral bear (Ursavus) and the panda (Ailuropoda), and therefore established a new genus and species, named *Ailurarctos lufengensis*.

To further demonstrate the reliability of the classification of *Ailuropoda lucida*, they specifically compared it with *Phanterus gerberis*, discovered in 1942 at the Hatvan site in the Panno Basin, Hungary. They (Qiu Zhanxiang and Qi Guoqin, 1982) found that *Ailuropoda lucida* and *Phanterus gerberis* share both similarities and differences in tooth morphology. The similarities include: both have double-rooted lower premolars, three-cusped crowns, and the anterior cusp of the lower first molar is not steep, with a low protocuscendant and an anterior posterior cusp. The differences are: *Phanterus gerberis* is significantly larger, with higher tooth cusps, fewer crown wrinkles, and dates to the end of the Late Miocene (7 million years ago); *Ailuropoda lucida* is significantly smaller than *Phanterus gerberis*, with lower tooth cusps, more crown wrinkles, and dates to the beginning of the Late Miocene (8 million years ago).

The morphological differences between the Ge's suburban panda and the Lufeng panda indicate that they are not on the same evolutionary level. The former is an extinct side branch of the panda family, leaving no living descendants. The pandas of China are unrelated to it.

The identification of the Lufeng panda as the first panda in China laid the foundation for the idea that the panda originated in the land of China.

Yuanmou Panda (Ailurarctos yuanmouensis)

Following the discovery of the Lufeng Panda, the Yuanmou Panda was discovered in Xiaohe and Zhupeng in the northern part of the Yuanmou Basin in Yunnan Province in 1987.

The stratigraphic position of the Yuanmou Panda fossils and their distribution in cross-sections

In 1997, Gao Feng, Ji Xueping, and others from the Yunnan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology made the following description of the fossil stratigraphy and lithology of Xiaohe and Zhupeng:

(16) A layer of grayish-white, yellow, and variegated silty clay containing ancient ape fossils, with a thickness of 7.0 m.

(15) A thick layer of purplish-red fine sand, 4.0 m thick.

(14) Brownish-yellow sand and gravel containing mammal fossils, 0.5m thick.

(13) Purplish-red silty clay, 7.0m thick

(12) Yellowish-brown fine sand interbedded with sub-clay, containing fossils of early pandas, ancient apes, etc., with a thickness of 2.0m.

(11) Purplish-red silty clay, 3.5m thick

(10) Light yellow gravel, 1.5m thick

(9) Purplish-red silty soil, 3.5m thick

(8) Red sub-clay, with alternating layers of silt and clay, thickness 4.0m

(7) Yellowish-brown and grayish-white fine sandy soil, containing ancient ape fossils, with a thickness of 1.5m.

(6) Interlayers of purplish-red clay, sub-clay, and silt, with a thickness of 12.0 m.

(5) Yellow gravel containing fossils of early pandas and ancient apes, with a thickness of 1.0m.

(4) Red sub-clay, silt, thickness 6.8m

(3) Brownish-yellow sub-clay, 0.6m thick

(2) Purplish-red sand, 9.0m thick

(1) Purplish-red clay and sub-clay, 3.2m thick.

The fossil material of the Yuanmou Panda is relatively scarce, totaling 6 pieces. There are 4 pieces in layer (12): one is a right maxilla with a fourth premolar, a first molar and a second molar; one is a left upper second molar; one is a left lower second molar and one is a right lower second molar. There are 2 pieces in layer (5): one is a left lower second premolar and one is a left lower first molar.

The positioning of Yuanmou Panda

Based on the morphological characteristics of the Yuanmou Panda fossil, researchers (Zong Guanfu, 1997) concluded that: (1) the individual was smaller than the Lufeng Panda, but the tooth morphology was basically similar to that of the Lufeng Panda; (2) the cusps of the premolars were more developed than those of the Lufeng specimen, and their morphology was closer to that of a panda. For example, the anterior and posterior cusps of the upper fourth premolar were the same size, and the inner cusps were split; the length of the triangular seat of the lower first molar exceeded that of the calcaneus, and the cusps of the crown were prismatic and accompanied by nodular protrusions; (3) the era (7 million years ago) was later than that of the Lufeng Panda (8 million years ago). In comparison, the Yuanmou specimen was slightly more advanced in evolutionary terms than the Lufeng specimen, so it was established as a separate species and named Yuanmou Panda (Ailurarctos yuanmouensis).

The discovery of the Yuanmou Panda adds a new member to the genus Ailuropoda, further supporting the theory that pandas originated in China.

II. Red Panda

In terms of evolutionary chronology, the first panda is the ancestor; in terms of discovery time, the red panda is the oldest, having been discovered in 1956. The discovery of the red panda can be traced back to the discovery of the first Gigantopithecus mandible.

Gigantopithecus Leads to "Golden Phoenix"—Red Panda

In the early 1950s, an eight-member cave exploration team led by Pei Wenzhong arrived in Nanning, Guangxi. The day after their arrival, on December 25, 1956, they received a call from the Liuzhou Municipal Bureau of Culture, reporting that they had obtained a mandible fossil resembling a human from a farmer. That afternoon, the Bureau sent someone to deliver the specimen to Nanning. Mr. Pei Wenzhong, already overjoyed, was stunned by this unexpected human-like specimen. It was clear that the excitement he felt 26 years earlier when he discovered the first Peking Man skull was once again evident on his face. He instructed the expedition team to contact Liuzhou as soon as possible and simultaneously dispatched Huang Wanbo and another member of the Guangxi Museum team to Liuzhou for investigation.

With the assistance of the Liuzhou Municipal Bureau of Culture, after several days of investigation, the discoverer of the "human"-like mandible, Qin Xiuhuai, was finally found.

Qin Xiuhuai is a simple farmer. He told us about the discovery of the mandible that resembled a "human".

He said, "When I was a child, I often heard my elders say that the rocky mountains here were full of caves filled with mud. Because of their age, the mud could be used as fertilizer for cultivation (tests have shown that this mud contains chemical substances such as aluminum, calcium, potassium, iron, carbonate, and phosphate). Not only could these things be used as fertilizer, but sometimes you could also find valuable 'dragon bones' in the mud. For this purpose, I often searched in the caves near the village."

One day, I came to Lengzhai Mountain on the banks of the Liujiang River, carefully climbed up the Xiaoyan Cave, and searched for mud near the cave entrance. Before long, I dug out a lot of mud, and to my excitement, I found "dragon bones" in the mud.

In the evening, I carried the mud and the "dragon bone" home together.

On December 25, 1956, I packed a load of "dragon bones" and carried it to the Luoman Supply and Marketing Cooperative purchasing station to sell.

On the way, I met Wei Yueshe, the director of the Luoman branch of the People's Bank of China. He saw that I was picking out "dragon bones" and started talking to me.

Where did all these "dragon bones" come from?

I said: It was dug from the Nitrous Oxide Cave.

Wei Yueshe chimed in, "Can I take a look?"

After I put down the load, I said: Okay.

Wei Yueshe then picked up a piece that looked like a human jawbone from the "dragon bone" of the carrying pole, weighed it in his hand, and said: "It's so heavy! This thing might have scientific research value!" So he persuaded me to donate it to the government.

I saw that he was a government official, so I agreed.

When our visit ended, I told Qin Xiuhuai that the mandible-like bone had been sent to Nanning and given to Professor Pei Wenzhong. Professor Pei said that it was not a human mandible, but the mandible of the Gigantopithecus that the expedition team was looking for.

Based on the information provided by our investigation, Mr. Pei Wenzhong decided to carry out formal excavation work on Xiaoyan Cave.

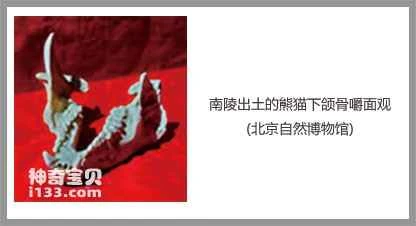

Excavations at Xiaoyan Cave began in 1957 and ended in 1964. There were six excavations, yielding thousands of vertebrate fossils. Among them were three Gigantopithecus mandibles and 1,000 teeth. Ten teeth of a Lesser Panda were unearthed at the site where the first Gigantopithecus mandible was discovered; and at the site of the second Gigantopithecus mandible, the world's first complete Lesser Panda mandible was obtained.

According to Mr. Pei Wenzhong's statistics, a total of 79 fossils of the Lesser Panda were unearthed from Xiaoyan Cave. Four mandibles were found, with specimen V.1992 being the best preserved, its incisors, canines, premolars, and molars clearly distinguishable. The remaining fossils consisted of individual teeth, totaling 73: one upper third premolar, eight upper fourth premolars, eleven upper first molars, fifteen upper second molars, seven lower fourth premolars, ten lower first molars, twelve lower second molars, and nine lower third molars. These fossils were all buried in the same stratum as the Gigantopithecus fossils.

This is the origin of the earliest discovery of the red panda.

Why is it called a baby panda?

The scientific name for the red panda was given by the renowned paleoanthropologist Pei Wenzhong. His reasoning for the name was as follows:

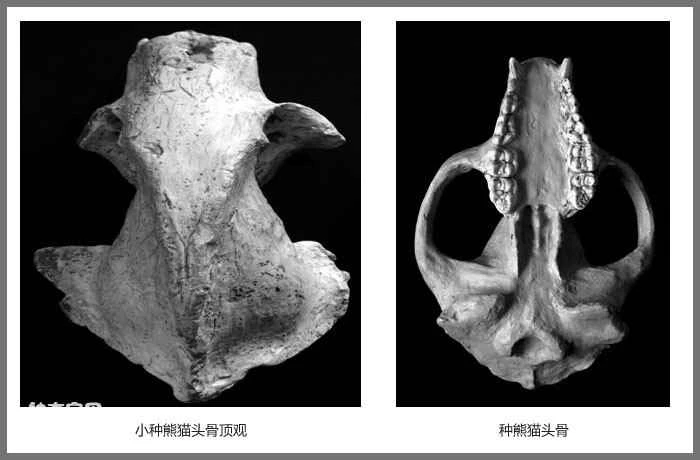

(1) The first miniature panda mandible (number V.1992) is shorter than that of other pandas (such as Panda bashi and extant pandas); (2) The teeth of V.1992 have some primitive characteristics, such as fewer wrinkles on the tooth surface, no cusps on the inner surface of the main cusp of the upper fourth premolar, and no enamel protrusion at the junction of the crown and the root, commonly known as the tooth band. This phenomenon can also be seen on other teeth; (3) The tooth surface area (length × width) of the lower second molar is smaller, about one-third that of Panda bashi or extant pandas.

Based on the above analysis, Pei Wenzhong believes that the small panda of Xiaoyan Cave is clearly different from the Bashir panda and extant pandas. Furthermore, this panda dates back to an earlier period, specifically the early Pleistocene (about 2 million years ago). Therefore, based on its small size and related characteristics, Mr. Pei Wenzhong gave it a scientific name: *Ailuropoda microta*.

The discovery and identification of the red panda has brought a major highlight to the understanding of the close lineage between the early panda and the modern panda:

It is the direct ancestor of the modern panda.

Unfortunately, in recent years, with the continuous discovery of fossils of the small panda, some media outlets or researchers have referred to this small panda as a "dwarf".

We know that every species on Earth has its own specific organism and functions during the evolutionary process. If its organism and functions change due to natural factors, it no longer belongs to the original species. In the case of the Lesser Panda, if its organism and functions had changed through natural selection, then that would be a different story. However, this is not the case. In his research report, "Fossils of Carnivora, Proboscis, and Rodentia from Gigantopithecus Cave and Other Caves in Liucheng, Guangxi, 1987," Pei Wenzhong, when describing the morphological characteristics of the Lesser Panda, never mentioned any changes in its organism and functions. Instead, from the perspective of biological evolution, he viewed it as a once widely and continuously distributed, normally developed species.

I have observed panda fossils from multiple locations. Based on their measurement data and comparison with similar specimens, I have not found any individuals with abnormal development. Moreover, they are in the same evolutionary lineage as their ancestors, Ailuropoda melanoxylon and Ailuropoda basilica.

III. Wuling Mountain Panda

In the winter of 1978, a field team composed of Wang Linghong, Lin Yufen, Chang Shaowu from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Yuan Jiarong from the Hunan Provincial Museum discovered Wuling Mountain panda fossils in a cave deposit in Dongpaoshan, Baojing County, while conducting an investigation in northwestern Hunan.

The discovery of the Wuling Mountain panda

The Wuling Mountain panda habitat is located in a limestone cave in Dongpao Mountain, Baojing County, Hunan Province. The cave is rich in deposits, containing many mammal fossils. According to Chang Shaowu, the technician who excavated the Wuling Mountain panda fossils, on a sunny day, shortly after starting work after breakfast, a gibbon tooth was discovered in yellowish-gray sandy clay not far from the cave wall. When unearthed, the specimen was covered in light yellow sandy soil, which was firmly cemented. The tooth gleamed under the flashlight, greatly piquing the interest of the excavator. Wang Linghong, the team leader standing beside me, said, "Gibbons are a Class I protected animal in China." In Pleistocene fossil sites in southern China, gibbons, pandas, and Gigantopithecus are often found buried together. Could this phenomenon occur here? We need to pay close attention.

Chang Shaowu continued: Perhaps it was a coincidence, but panda fossils were indeed found in the same stratum where the gibbons were unearthed. Unfortunately, Gigantopithecus was not found.

Wuling Mountain Panda Fossil Strata and Their Distribution in Sections

According to Wang Linghong's description, the strata containing Wuling panda fossils consist of the following four layers:

(1) Stalactite slab containing fossils of Chinese mastodons. Thickness 30cm;

(2) Light brown sub-clay. Thickness 30cm;

(3) Light yellow silty soil, calcareous cemented. Contains fossils of Wuling Mountain panda, gibbon, saber-toothed elephant, rhinoceros, tapir, wild boar, deer, water buffalo, etc., 30cm thick;

(4) Dark brown sub-clay, containing no fossils. Visible thickness 10cm.

Positioning of Wuling Mountain Panda

To accurately locate the panda fossils from the Wuling Mountains, Wang Linghong, Yuan Jiarong, and others observed panda specimens unearthed at Bijia Mountain in Liuzhou, Guangxi, and Longgudong in Jianshi, Hubei. They found that the materials from Wuling Mountain in Hunan, Longgudong in Hubei, and Bijia Mountain in Guangxi were remarkably consistent in tooth morphology and individual size. Therefore, they studied the materials from these three locations (Dongbaoshan, Longgudong, and Bijia Mountain) together, and designated specimen V. 5097 from Longgudong in Jianshi, Hubei, as the holotype specimen.

Wang Linghong, Yuan Jiarong, and others believe that the basic characteristics of specimen V. 5097, such as the cusps of the teeth and the enamel wrinkles on the occlusal surface, are intermediate in development between those of the Lesser Panda and the Bashi Panda. Furthermore, the length and width of the upper fourth premolar and the lower first molar are also intermediate between those of the Lesser Panda and the Bashi Panda.

Red panda

The upper fourth premolar is 20mm long and 13mm wide; the lower first molar is 18mm long and 21mm wide.

Wuling Mountain Panda

The upper fourth premolar is 24mm long and 17mm wide; the lower first molar is 23mm long and 25mm wide.

Bass panda

The upper fourth premolar is 28mm long and 19mm wide; the lower first molar is 27mm long and 29mm wide.

The above characteristics indicate that the pandas in Wuling Mountain, Jianshi and other places are a transitional member between the lesser panda and the Bashi panda, and can be regarded as a new subspecies, Ailuropode melanoleuca wulingshanensis (Latin meaning: panda Wuling Mountain subspecies).

Based on the ancient nature of the associated fauna, such as the long-extinct mastodons, porcupines, and piglets, researchers have determined that the Wuling Mountain panda dates back to the late Early Pleistocene, approximately 1.6 million years ago.

IV. Panda barbarum

The discovery of Panda bacon

The first discovery of the Panda bacon was not in China, but in neighboring Myanmar.

In 1915, miners discovered several mammal fossils in a cave deposit at the Ruby mining area in Mogok, Burma. Among them was a complete maxilla, with several teeth preserved. Researcher Woodward believed that the morphological features of this jawbone specimen closely resembled those of the extant panda from the western mountains of China. However, there were differences, such as the second premolar having a single root and the first premolar possibly being missing—features unique to the Mogok specimen. Considering the fossil's location in a cave deposit and its early age, a separate species name was proposed: *Ailuropoda baconi*.

Renaming of the species of Panda Barthélemy

In the autumn of 1921, American paleontologist Walter Granger ventured alone into the Three Gorges and discovered panda fossils in limestone fissure deposits in Pingba Village, Yanjinggou, Wanxian County, Sichuan Province. The materials included a well-preserved skull, mandible, and a single tooth. In 1923, he and Matthew studied these specimens and concluded that the skull had a short face, high parietal and forehead prominences, robust and broad zygomatic arches, well-developed sagittal ridges and intervertebral grooves, and a relatively flat occipital region, forming an isosceles triangle. The teeth were closely spaced without gaps; the molars were wider than long, and the occlusal surfaces were covered with enamel wrinkles of varying coarseness.

These morphological characteristics of the Yanjingou specimen differ from both extant pandas and the pandas of Mogok Cave in Myanmar. Therefore, researchers have designated a new species, called the cave panda (Ailuropoda fovealis).

In 1953, Colbert and Hao Yijie (E.H. et D.A. Hooijer) re-examined the panda materials from Yanjingou, Wanxian, Sichuan. They advocated merging the Yanjingou specimens with extant pandas into the same genus and species. However, considering the unique features of the Yanjingou specimens—such as less pronounced retroorbital narrowing of the skull, a thicker and lower sagittal crest, and a slightly wider occipital bone—they argued that these differences should only be considered regional variations and not grounds for establishing a new species. Therefore, Colbert et al. revised the cave species *fovealis* established by Granger et al. to a cave subspecies, *Ailuropoda melanoleua fovealis* (Latin for panda cave subspecies).

The species name of the panda barbarian returns to its original name.

Shortly after the founding of the People's Republic of China, a cave exploration team led by Professor Pei Wenzhong unearthed a large number of panda fossils in hundreds of caves in Guangxi, Guangdong, Hunan, Hubei, and other places. The materials included skulls, mandibles, and teeth.

In 1972, Wang Jiangke, in his paper "A Study on the Classification, Geological Distribution and Evolutionary History of the Giant Panda," based on information from panda fossils collected by the South China Cave Expedition Team, explicitly proposed that the panda fossils from Mogok, Myanmar, studied by Woodward in 1915, despite limited material, shared dental morphological characteristics with those of the panda from Yanjinggou, Wanxian, Sichuan, and should be grouped into a single subspecies. Following the priority rule of international nomenclature, the cave subspecies *fovealis* was changed to the *baconi* subspecies, ultimately becoming *Ailuropoda melanoleua baconi*. Its Chinese name thus became the Giant Panda *Baconi* subspecies.

In 1993, Huang Wanbo praised Wang Jiangke's views in his article "The Evolutionary Significance of Panda Skull, Mandible and Tooth Features" and has continued to use the name "Bartholin's subspecies" ever since.

V. Extant Pandas

In terms of physical characteristics, living pandas are similar to those of the Panda basilica, except that they are slightly smaller. Other aspects, such as diet, clothing, and behavior patterns, are not different, so we will not go into details here.

Most readers may not be familiar with certain physical structures and physiological functions of the living panda, a "pet" loved and followed by people all over the world. Here are a few examples.

fake thumb

Despite their seemingly clumsy appearance, pandas possess remarkably dexterous fingers. Like humans, they grasp bamboo stalks with their "hands," using their pseudo-thumb to pluck bamboo leaves along the stalk, gathering a handful before chewing them. This astonishingly agile movement is entirely due to the function of their pseudo-thumb.

Zoologists have analyzed pandas' "fingers" from an anatomical perspective, concluding that in addition to the five phalanges in their normal positions, pandas possess a thumb—a pseudo-thumb. This pseudo-thumb is not a finger and is fundamentally different from the occasional extra sixth finger found in humans. The panda's pseudo-thumb is composed of sesamoid bones and connected to the metacarpal bones by muscles, enhancing its strength and flexibility, allowing it to rotate inward. In a sense, the appearance of the pseudo-thumb, like an enlarged skull and widened teeth, is a specialization phenomenon designed for bamboo consumption. In contrast, the black bears and brown bears familiar to humans do not develop pseudo-thumbs because they do not feed on bamboo.

We know that the panda family has had six members since 8 million years ago. Did they all have a pseudothumb? The author believes that *Ailuropoda spp.* lacked it. *Panda minimus* already had a rudimentary pseudothumb. From *Panda wulingshanensis* to *Panda bashi*, their pseudothumb gradually became more refined as their bamboo intake increased. Unfortunately, no pseudothumb fossils have been found to date. This may be because it was too small to attract the attention of excavators.

I believe that the mystery of the pseudo-thumb fossil will be solved in future excavations!

In summary, from the earliest panda to the extant panda, according to its systematic classification, there are 1 family, 2 genera, 4 species, and 2 subspecies, namely:

Pocock, Ailuropodidae, 1929

The first genus of panda, *Ailurarctos* Qiu et Qi, 1989

The first giant panda of Lufeng, *Ailurarctos lufengensis*, Qiu et Qi, 1989

Yuanmou, the first panda, *Ailurarctos yuanmouensis* Zong, 1991

Ailuropoda (Alphonse Milne—Edwards), 1870

Red panda, Ailuropoda microta Pei, 1987

Wulingshan panda subspecies *Ailuropoda milanoleuca wulingshanensis*

Wang et al, 1982

The subspecies of the Baconi ape, *Ailuropoda milanoleuca* baconi (Woodward), 1915

The extant panda, *Ailuropoda milanoleuca* (David), born in 1869.