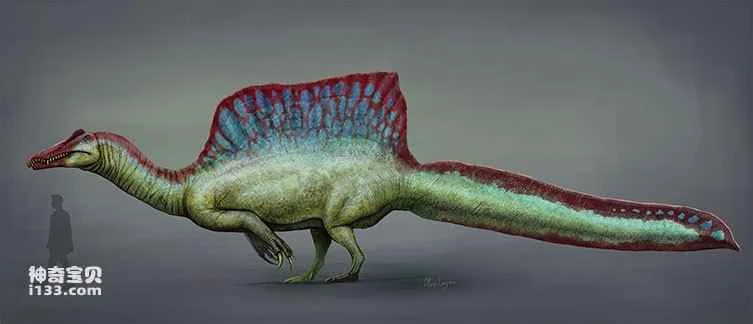

We modern humans are members of the genus *Homo*, which evolved from *Homo habilis* through *Homo erectus* and early *Homo sapiens*. Why did only the early members of the genus *Homo* evolve into modern humans, while the various Australopithecus species that also lived at that time failed to continue developing and went extinct? What competitive advantages did the genus *Homo* possess? Before we discuss the specific process of the development of the genus *Homo*, let's first understand its advantages.

I. A Leap in Brainpower

All Australopithecus had small brains, large cheek teeth, and protruding jaws, and employed an ape-like survival strategy. They primarily ate plant-based foods, and their social relationships likely resembled those of modern baboons living in tropical savannas. They were similar to humans only in their locomotion; otherwise, they shared no similarities.

Compared to Australopithecus, Homo habilis exhibited a leap in brain size; moreover, their teeth changed, showing adaptation to a shift in diet (more carnivorous). But that's not all. New research into the biology of our human ancestors reveals that many other aspects of the genus Homo also changed, causing this creature to jump from the ape-like end to the more human-like end.

II. Unique Growth Curve

One of the most important characteristics of modern humans is that infants are born vulnerable and helpless. During their growth, they must go through a long childhood followed by a period of rapid growth during puberty, when their height increases at an astonishing rate. This phenomenon is unique to humans among extant mammals; most mammals, including apes, go almost directly from infancy to adulthood. In modern humans, the increase in body size during the rapid growth of puberty from adolescence to adulthood is approximately 25%; in contrast, chimpanzees have a very stable growth curve, increasing in size by only 14% from youth to old age.

So why do modern humans exhibit this unique growth curve? It turns out it's related to the intense learning process that humans must undergo during growth. If there's a significant size difference between a growing child and an adult, the child will develop a sense of awe towards the adult, establishing a teacher-student relationship, which facilitates better learning. However, if human children rapidly reach near-adult height following a growth curve similar to that of apes, they might develop a sense of rivalry rather than awe towards adults. After the relatively long and arduous learning period, the human body can "catch up" through the accelerated growth spurt of puberty.

The reason modern humans require such a long period of intensive learning is that, in the process of growing up, they not only need to learn skills to sustain themselves, but also cultural aspects such as traditional family relationships and rules of life. Culture is a unique adaptation possessed only by humans in the entire animal kingdom, made possible by the unusual growth and development patterns during childhood and adulthood.

III. The Weak and Helpless Infancy

However, the weakness and helplessness of modern human newborns is not a cultural adaptation, but a biological phenomenon: because humans have large brains but restrictive pelvic structures, human babies are born relatively early.

Brain size is not only related to intelligence but also to important life events such as weaning age, age of sexual maturity, gestation period, and lifespan. Compared to animal species with smaller brains, related species with larger brains tend to have later weaning, later sexual maturity, longer gestation periods, and longer lifespans. An extrapolation based on comparisons with other primates suggests that for a newborn's brain volume to be proportional to their body size, the gestation period for modern humans, with an average brain volume of 1350 ml, would need to be 21 months, not the actual 9 months. This means that human infants are born with brains far smaller than they should be; they need an additional year of development to catch up; therefore, they are inevitably weak and vulnerable at birth.

So why can't modern humans give birth to babies with adequate brain capacity and self-reliance after 21 months of pregnancy? Why does nature expose human newborns to the dangers of entering the world so early? This is determined by the large brain and relatively narrow pelvic opening of humans.

A common trend in the ontogeny of both apes and humans is that brain development outpaces physical development; that is, brain volume rapidly reaches adult levels early in life. The average brain volume of an ape newborn is about 200 ml, roughly half that of an adult. Therefore, ape newborns possess a certain degree of self-reliance. If modern humans were to give birth to newborns with similar self-reliance, their brain volume would likely reach 675 ml. For human females, delivering an infant with such a large brain is exceptionally difficult, sometimes even threatening the mother's life. During human evolution, the pelvic opening has widened to accommodate the increasing size of the infant's brain; however, this widening is limited by bipedal locomotion. When the average newborn's brain volume reaches the current 385 ml (about one-third of an adult's), the human pelvic opening has effectively reached its limit.

From newborn to adult, the human brain doubles in size, while the ape brain only doubles. This different pattern of brain development is itself an important aspect that distinguishes humans from apes.

Conversely, consider the average human newborn's brain volume of 385 ml. Twice that is 770 ml. If a higher primate exceeds this volume in adulthood, it means their brain volume had to more than double during development. This implies a developmental pattern of infants entering the world weakly and helplessly "prematurely," suggesting they were more human-like and less ape-like in their developmental type. In this light, *Homo habilis*, with an adult brain volume of approximately 800 ml, seems to have just left the branching point between humans and apes and was beginning its journey towards humanity. Early *Homo erectus*, with a brain volume of approximately 900 ml, clearly showed they were already moving towards human characteristics.

Tecana Boy

Based on fossils of the "Tekkalan boy," a Homo erectus discovered in 1984 on the western shore of Lake Tekkalan in northern Kenya by Richard Leakey's research team, Johns Hopkins University anatomist Alan Walker speculated that the pelvic opening of Homo erectus was smaller than that of Homo sapiens, and the brain volume of a Homo erectus newborn was approximately 275 ml. This volume is significantly smaller than that of a modern human newborn; however, it is exactly one-third the brain volume of an adult Homo erectus, a proportion similar to that of modern humans. This means that Homo erectus infants, like modern humans, were vulnerable at birth.

Because the pelvis of *Homo habilis*, the direct ancestor of *Homo erectus*, has not yet been discovered, scientists cannot make similar calculations for *Homo habilis*. If *Homo habilis* infants had brains as large as those of *Homo erectus* newborns at birth, they would also have been born "prematurely," just not as "severely" as *Homo erectus*; they would also have been weak and helpless at birth, but this state would have lasted shorter than that of *Homo erectus*; they would have also lived in a human-like social environment, only their social environment would have been simpler and more primitive. Therefore, it can be inferred that from its very beginnings, the genus *Homo* began to live, develop, and cope with the challenges of nature in a completely different way than before. Conversely, although various *Australopithecus* species had also stood upright and taken their first steps, they still possessed relatively small brains similar to apes, and thus their early development still followed a pattern similar to that of apes.

IV. The Extension of Childhood

From the earliest genus Homo, humans have needed meticulous care from their parents during the long, vulnerable period of infancy. But what about the rest of childhood? How long does childhood need to last for human children to learn enough skills and culture, gain enough practical experience, and successfully enter and navigate the subsequent rapid growth of adolescence?

The extended childhood of modern humans is due to their slower physical growth compared to apes. Therefore, any significant milestone in human life history occurs later than in apes. For example, the eruption of the first permanent molar occurs in humans around age 6, while in apes it is around age 3; the eruption of the second permanent molar occurs in humans between age 11 and 12, while in apes it is around age 7; and the emergence of the third permanent molar occurs in humans between age 18 and 19, while in apes it is around age 9.

In the late 1980s, Holly Smith, an anthropologist at the University of Michigan, developed a method to deduce the life history types of fossil humans by linking brain size with the age at which the first permanent molar erupted. She synthesized data from humans and apes as a baseline and compared it with fossil humans, resulting in three life history types: 1. Modern human type, with the first permanent molar erupting at age 6 and an average lifespan of 66 years; 2. Intermediate type; 3. Ape type, with the first permanent molar erupting slightly older than 3 years and an average lifespan of approximately 40 years. In this analytical framework, all Australopithecus belong to the ape type; Late Homo erectus, living approximately 800,000 years ago, like Neanderthals, belongs to the modern human type; Early Homo erectus belongs to the intermediate type. For example, the first permanent molar of the Tcana boy (an Early Homo erectus living 1.6 million years ago) likely erupted when he was slightly older than 4 and a half years old, and if he hadn't died at age 9, he could have expected to live to about 52 years old.

Smith's analysis sparked heated debate at the time, as conventional wisdom held that all members of the human family, including Australopithecus, followed a slow, anthropogenic growth pattern in their early stages. How could they prove who was right and who was wrong? Just then, anatomists Christopher Dean and Tim Bromage at University College London devised a method for directly determining tooth age: under a microscope, lines on teeth, like tree rings, could indicate age. Dean and Bromage applied their technique to paleoanthropology, studying the mandible of an Australopithecus. In terms of tooth development, this mandible was comparable to that of a child named Toon, with its first permanent molar erupting. The lines on the teeth indicated that the individual died shortly after the age of three; the observations precisely demonstrated that the growth curve of Australopithecus followed an ape-like pattern.

Dean and Bromage examined other types of human teeth fossils and discovered three types consistent with Smith's conclusions: the modern human type, the intermediate type, and the ape-like type. Among them, Australopithecus was the ape type, early Homo erectus was the intermediate type, and late Homo erectus and Neanderthals were the modern human type.

These research findings once again sparked controversy. This debate only ended after anthropologist Glenn Conroy and clinician Michael Vannier of Washington University in St. Louis brought advanced technology from the medical field to anthropological laboratories. Using computer-aided 3D CT scanning, they examined the interior of the Toon Child's mandible fossil, essentially confirming Dean and Bromage's conclusion that the Toon Child died at approximately three years old and was an infant following an ape-like growth curve.

New technologies, such as using fossils to study key events in life history and inferring biological characteristics by examining tooth development, have propelled paleoanthropology to a new level. Using these techniques, we can infer that the Tkanna boy was weaned before the age of four; if he survived, he would have reached sexual maturity around age 14; and his mother likely gave birth to her first child at age 13.

V. Significant Changes in Social Structure

The evolution of early Homo members toward modern humans in terms of growth and development occurred under specific social conditions. All primates are social, but modern humans have developed their social skills to the highest degree. Biological changes inferred from evidence on the teeth of early Homo members tell us that their social interactions had begun to intensify, and they had created a culture-building social environment; moreover, the entire social structure underwent significant changes, which can be clearly seen by comparing the proportions of male and female body shapes and contrasting these proportions with those of other known primates.

baboon

Hermaphroditism exists in baboon populations living in tropical savannas, where males weigh twice as much as females. This hermaphroditism only occurs when there is intense competition among adult males for mating opportunities with females. Like most primates, male baboons leave their original groups upon reaching adulthood to join nearby groups, where they then compete with other males already established. This male migration pattern means that males within most baboon groups are generally not related, thus eliminating the Darwinian reason (i.e., genetic reason) that necessitates cooperation based on shared genes.

chimpanzee

In contrast, within chimpanzee groups, males remain in their birth group, while females migrate to other groups. As a result, males within the same group are brothers, sharing half of their genes. Therefore, there is a Darwinian reason for their cooperation in acquiring females. They cooperate to fight off other chimpanzee groups; in occasional hunting trips, they often cooperate to corner a monkey in a tree and then capture it. This lack of competition and increased cooperation among males is reflected in the male-to-female body ratio, unlike in hermaphroditism, where males are only 15%–20% larger than females.

In terms of the size ratio between males and females, various Australopithecus species conform to the baboon model. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that the social life of Australopithecus was similar to that of modern baboons. Looking at Peking Man, a typical representative of Homo erectus, the difference in size between males and females was smaller than that of Australopithecus, but larger than that of modern humans. However, when comparing this to early Homo sapiens, we find that men were only 20% larger than women. Anthropologists Robert Foley and Phyllis Lee of Cambridge University believe that this change in the male-to-female size ratio at the origin of Homo sapiens must have reflected changes in social structure. Early Homo sapiens men likely remained in their birth groups with their full brothers, while women migrated to other groups; this arrangement would inevitably have promoted cooperation among men.

So, what caused this change in social structure? Some anthropologists believe that close cooperation among men was beneficial in defending against attacks from neighboring groups. However, more evidence suggests that this change was more likely due to a shift in the diet of Homo sapiens—meat became a crucial source of energy and protein. Hunting for large quantities of meat inevitably required greater cooperation among men within the same group.

VI. Increased carnivorousness

The increased carnivorousness of humans is evident in various aspects of their morphology and physiology.

The teeth and jawbone structure of early Homo sapiens differed from those of Australopithecus, indicating a stronger carnivorous diet.

The increased brain size of early hominins also indicates an increased carnivorous diet. Biologists have proven that the brain is a major energy-consuming organ in animal metabolism. For example, in modern humans, the brain accounts for only 2% of body weight but consumes 20% of the body's total metabolic output. Primates are the animal group with the largest relative brain size, and the human brain size far exceeds that of typical primates. If body weight were comparable, the human brain would be three times the size of an ape's. Therefore, the increased brain size of early hominins must be linked to the acquisition of higher energy. In other words, the food of early hominins had to be both reliable and nutritious. Such food resources could only be meat, because only meat is the most efficient concentrated source of calories, protein, and fat. All of this suggests that early hominins could only develop a brain larger than that of Australopithecus by significantly increasing the proportion of meat in their diet.

VII. They have a stronger ability to adapt to different types of exercise.

Besides teeth, jawbone, and brain size, early hominins also showed greater adaptability than Australopithecus in other physical aspects. These physical characteristics indicate that although Australopithecus was bipedal, its agility was still relatively poor; while early hominins were agile and began to run effectively.

This conclusion was first drawn from the research of anthropologist Peter Schmid at the Zurich Institute of Anthropology on Lucy. He constructed a full skeleton of Lucy using fiberglass models of fossil remains and found that her ribcage was conical, like an ape's, rather than barrel-shaped like a human's; moreover, Lucy's shoulders, torso, and waist were also ape-like. Therefore, Schmid explained that the Australopithecus afarensis, which Lucy represented, could not raise its chest to perform the deep breathing we experience when running. Furthermore, their large bellies and lack of a waist limited their flexibility; flexibility is crucial for human running.

On the other hand, Leslie Airow measured the length and weight of modern humans and apes, comparing them to those of fossil humans. Modern apes were robust, weighing twice as much as a human of similar height; in contrast, Australopithecus were ape-like, while all members of the Homo genus were as lithe and agile as modern humans.

Recalling the initial adaptive significance of bipedalism, we remember it arose as a more efficient mode of locomotion in a changing natural environment. It allowed bipedal apes to survive and thrive in habitats unsuitable for typical ape life. While searching for abundant food resources in open, sparsely wooded areas, bipedal apes could move across a larger area. When the genus *Homo* evolved, a new mode of locomotion emerged—still bipedal, but far more agile and flexible. The nimble and lightweight physique allowed early *Homo* to walk and even run with long strides; simultaneously, it effectively dissipated the heat generated by such vigorous activity, which was especially important for early *Homo* members living in the hot tropical savanna of Africa. Efficient, long-stride bipedalism represents a core change in human adaptation. This change is also closely related to the shift in human diet, as it facilitated active hunting.

The ability of an active animal to dissipate heat is particularly important for the physiological activity of its brain. Anatomical studies conducted by Dean Falk, an anthropologist at the State University of New York, in the 1980s confirmed that the structure of the blood vessels in the human brain indicates that the blood flowing from them can effectively cool the brain, while the situation was very different in Australopithecus.

Stronger support for the idea that the genus *Homo* possessed greater adaptability in locomotion comes from the anatomical structure of the inner ear in early humans, as revealed by computed tomography (CT) scans. All mammals have three C-shaped tubes in their inner ear, called semicircular canals. These three canals are perpendicular to each other, with two perpendicular to the ground. This structure of the semicircular canals plays a role in maintaining balance. Fred Spool, a scientist at the University of Liverpool, discovered that the two perpendicular semicircular canals in humans are much larger than those in apes. This phenomenon is clearly a special adaptation of bipedal, upright species (humans) to the specific balance required for an upright posture. Spool continued to examine early human fossils, and the results were indeed surprising: in all species of the genus *Homo*, the anatomy of the inner ear is indistinguishable from that of modern humans; while in all species of *Australopithecus*, the structure of the semicircular canals is ape-like!

Stone tools

8. Able to make tools

In conclusion, the physical superiority of the genus *Homo* compared to *Australopithecus* is self-evident. Let's now examine the clearest evidence of our ancestors' behavior—the most primitive tools made of stone.

2.5 million years ago, humans began to strike one stone against another to create sharp-edged tools (called stone tools), thus initiating the technological development process of humans actively adapting to, utilizing, and even transforming nature.

The earliest stone tools were small flakes, about 2.5 centimeters long, made by striking one stone against another, with remarkably sharp edges. These flakes, though simple, had many uses. Archaeologists Lawrence Keeley of the University of Illinois and Nicolas Toth of Indiana University discovered under a microscope different scratches on the flakes. Some scratches were from cutting flesh, some from chopping trees, and some from cutting softer plants like grass. Therefore, one can imagine that our ancestors once came to a simple camp by a river, using some flakes to cut down saplings to build a framework, and using other flakes to cut thatch to cover the framework, creating a simple structure. Then, under the shelter of this simple structure, they used other flakes to butcher their prey, beginning their primitive yet gradually evolving way of life.

The earliest stone tool assemblages discovered to date date back approximately 2.5 million years and include not only stone flakes but also larger tools such as choppers, scrapers, and various polygonals. In most cases, these stone artifacts were chipped from a single large block of rock. Mary Leakey studied this earliest technology for many years in Olduvai Gorge, thus naming it the Olduvai industry. This technology persisted until about 1.4 million years ago, and its basic characteristic was that whatever was chipped out was what it looked like, with no discernible pattern.

However, this seemingly unpredictable, "whatever you produce, that's what you get" technology ushered in a new era in human evolutionary history. When our ancestors discovered the knack for continuously producing sharp stone flakes, they suddenly gained access to food they had never been able to obtain before. These small flakes were highly efficient tools; they could cut through animal hides that were previously impossible for humans to bite with their teeth, thus exposing the meat. Therefore, those who made and used these simple stone flakes could obtain a new energy source—high-quality animal protein. This not only expanded their foraging range, but this new, highly efficient energy source also provided nutritional support for the increase in their brain size and increased their chances of successfully reproducing. Reproduction is a very energy-intensive process, and expanding one's diet, especially increasing meat consumption, makes the reproductive process more secure.

The Olduvai Industrial Age coincided with the coexistence of the earliest members of the genus *Homo* and many species of *Australopithecus*. So, who actually made these tools? The most reliable conclusion is that of *Homo*. On the one hand, *Homo* possessed a more advanced intelligence (larger brain) capable of toolmaking; on the other hand, various *Australopithecus* species had distinctly different specific adaptations from *Homo*. Meat-eating in *Homo* was likely a significant part of this difference—for early humans lacking the sharp claws and teeth of carnivores, stone toolmaking was an essential part of their carnivorous capabilities; even without these tools, herbivores could survive.

While studying tools and experiments on toolmaking at archaeological sites in Kenya, Toth discovered that the earliest toolmakers were more right-handed than left-handed, just like modern humans. This right-handedness corresponds to brain asymmetry, which is absent in modern ape populations. This suggests that, as early as approximately 2 million years ago, the brains of Homo sapiens had already evolved into "true human brains."

In conclusion, the adaptation of the genus Homo was successful, and everything we humans have achieved today is proof of that.

9. Why are there only people...?

But why haven't other bipedal, upright species survived to this day and lived alongside humans?

Starting 2.5 million years ago, the genus Homo coexisted with several Australopithecus species in East and South Africa. However, around 1 million years ago, all of the Australopithecus went extinct. How did this fate come about?

Undeniably, the development of the genus *Homo* itself was the primary cause of this outcome. Early *Homo* populations likely increased rapidly, becoming major competitors with *Australopithecus* for essential food resources (although *Homo* increased its meat consumption, it still consumed large amounts of plant-based foods). Around 2 million years ago, with the emergence of *Homo erectus*, this competition further favored *Homo*, as it was an extremely successful species, being the first in human evolutionary history to migrate out of Africa. Furthermore, between 1 and 2 million years ago, baboons, a species within the terrestrial macaque superfamily, also evolved successfully and increased in number, continuing to compete with *Australopithecus*. *Australopithecus* likely became extinct under the dual competitive pressure exerted by both *Homo* and baboons.