When it comes to drawing the Tree of Life, the most important difference between humans and sharks isn't limbs and fins, or even lungs and gills. All the differences come down to their bones. Sharks have bones made of cartilage. They are called cartilaginous fish. However, like bony fish, humans and most other living vertebrates belong to another category—these creatures have bones made of bone.

Devonian fish fossils dating back approximately 415 million years have been discovered in Siberia.

Scientists already know that these two categories diverged around 420 million years ago, but who their last common ancestor was remains a mystery. Now, the secret discovered in the brain of a small fish fossil in Siberia, Russia, may offer some clues. The fossil material under discussion is a Devonian fish found in Siberia around 415 million years ago, complete with a skull and scales.

As early as 1992, a short scientific paper mentioned this fossil and classified it as a bony fish of the genus *Dialipina* based on the similarity of its scales and skull to the bony fish *Dialipina* from the Novosibirsk Islands. However, bony fish from the same period are extremely rare, so when paleontologist Martin Brazeau of Imperial College London discovered more detailed images of this Siberian fossil fish online, he and his colleagues Sam Giles and Matt Friedman of Oxford University believed that a more detailed study of the fish's origins would be invaluable.

To find out where this fish could have integrated into the evolution of early jawed vertebrates, researchers used a miniature CT scan technique—similar to the conventional CT imaging techniques used on patients in hospitals—to look inside their bodies, allowing them to observe the skeletal structure in their 1-centimeter-long skulls without damaging the fossils.

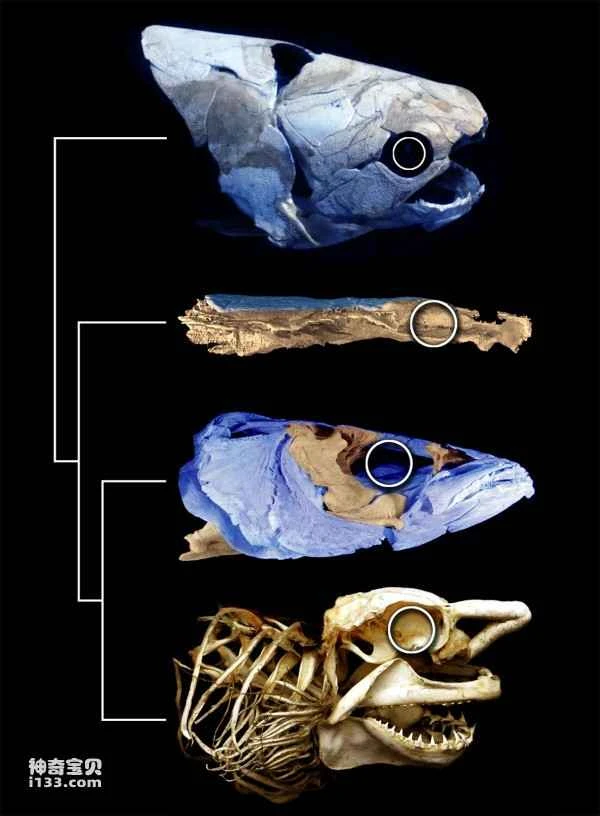

Researchers have discovered that although this fossil was previously classified as a bony fish based on its external morphology (such as the shape of the skull crest and the color of the scales), CT scans revealed a striking mosaic of features between cartilaginous and bony fish.

For example, the skull of this fish was composed of a large bony plate similar to that of today's bony fish, but the blood vessels and nerve traces around its head were more similar to those of cartilaginous fish.

Researchers reported the discovery in the online edition of Nature on January 12. They named the fish *janusiscus schultzei*, after the ancient Roman god Janus.

This discovery suggests that the common ancestor of two branches of jawed vertebrates possessed characteristics of bony fish, but these characteristics later disappeared in the lineage of cartilaginous fish, such as the bony plates of the skull.

This discovery supports a 2013 study that found several features thought to be unique to bony fish, such as the presence of large plate-like bones, actually appeared in shieldfish, an extinct jawed fish related to the ancestors of cartilaginous and bony fish.

This discovery also supports the findings of a 2014 study that showed a 325-million-year-old shark fossil possessed an astonishing number of bony fish characteristics, suggesting that its ancestors also had these characteristics, and that sharks may be more specialized than previously thought.

Giles, the first author of the new study, points out that these findings, on the whole, could correct the misconception that cartilaginous fish are more primitive than bony fish.

Unlike one category that is older than the other, "the two groups of organisms have evolved different adaptations, and they have also retained primitive characteristics that are different from their ancestors," Giles explained. "Each organism has found different ways to solve the problems they encounter in the ocean where they live."

"Janusiscus is a fascinating discovery," said John Long, a paleontologist at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia. He emphasized that it was an achievement that would have been impossible without sophisticated CT scans. "By revealing new information in these crucial transitional fossils, the use of this modern technology is changing the way we conduct paleontological research," Long said.

Cartilaginous fishes include sharks, rays, and silver sharks. Just before the extinction of shieldfish in the Devonian period, bony and cartilaginous fishes flourished. Although cartilaginous fishes successfully grouped together, their number of species (approximately 550) was still far fewer than that of modern bony fishes (approximately 20,000 species). Cartilaginous and bony fishes differed in many ways. The most obvious difference was that the skeletons of cartilaginous fishes were composed of cartilage. Although the vertebral column was partially ossified, true skeletons were lacking. Other characteristics included 5–7 pairs of gill slits; skin covered with shield-like scales with serrated structures; and a mouth lined with numerous teeth. Most cartilaginous fishes lived in marine environments, but some freshwater sharks also existed.