How birds, descendants of dinosaurs, survived the mass extinction event 65 million years ago has been a question scientists have long sought to answer. A meteorite impact and frequent volcanic activity filled the atmosphere with massive amounts of volcanic ash, plunging the Earth into perpetual darkness. This caused the death of countless plants that relied on photosynthesis, further depriving herbivorous dinosaurs of their primary food source, ultimately leading to the extinction of apex predators like Tyrannosaurus Rex. In this extinction event triggered by the collapse of the food chain, why did birds survive?

On April 21, the academic journal BMC Evolutionary Biology published online the research results completed by the team of Li Zhiheng from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and several collaborating institutions, including the Synchrotron Radiation Research Center. The research explored the evolutionary characteristics of teeth from non-avian dinosaurs to ancient birds, which are most closely related to birds. It revealed that the difference in diet between birds and dinosaurs may be the key to their ability to escape catastrophe and survive to this day.

Figure 1. An ecological reconstruction of a herbivorous ancient bird (left) and a small predatory dinosaur (right). Mesozoic birds, living in the same ecosystem as carnivorous dinosaurs, evolved different feeding habits, such as herbivorous feeding mainly on seeds and fruits, and omnivorous feeding on small insects, thus avoiding direct food competition with carnivorous dinosaurs. (Illustration by Zheng Qiuyang)

Figure 2. Fossil specimen of *Huibird*, an ancient bird from the Early Cretaceous. Collection of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. (Black arrows indicate tooth locations). (Photo provided by Li Zhiheng)

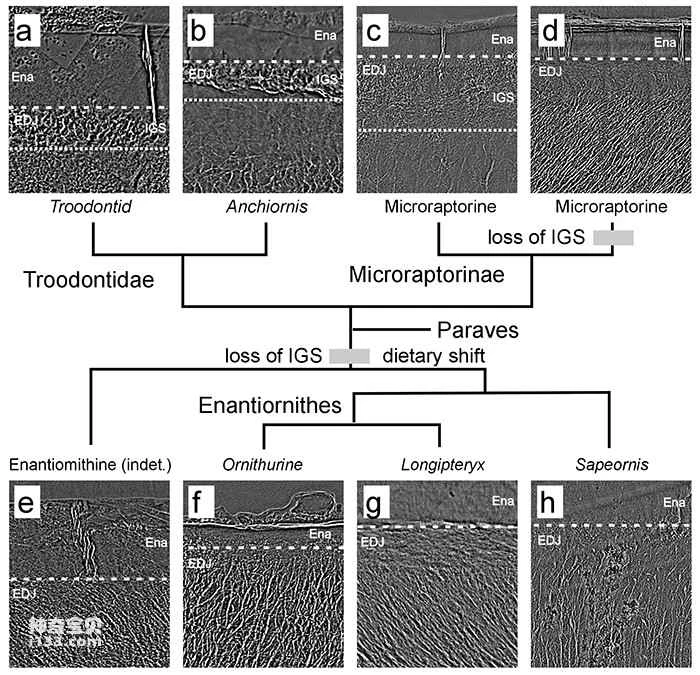

The research team used a high-resolution transmission X-ray microscope developed by synchrotron radiation to compare and study the microstructure of the teeth of small non-avian dinosaurs—including Troodon, Anchiornis, and Microraptor—and ancient birds (see Figure 2)—including Neanderthals, Enantiornithes, Ephemeropteryx, and Jeholornis. They found that although a simple enamel layer was preserved in early ancient birds, the porous mantle dentin layer (shown as IGS in Figure 3) between the enamel and dentin had disappeared. This porous mantle dentin layer is considered a special shock-absorbing protective structure developed in the teeth of carnivorous dinosaurs to prevent tooth breakage during predation. Not only in ancient birds, but also in a Microraptor specimen studied in this study, the mantle dentin layer had disappeared. This means that birds and some closely related dinosaurs no longer needed special mechanical protective structures for their teeth; indirectly confirming that their dietary habits, such as bite force and predatory behavior, differed greatly from those of carnivorous dinosaurs. Through dietary shifts, they avoided competition for food niches with carnivorous dinosaurs, greatly improving their adaptability and surviving the most difficult times. Compared to the general trend of herbivorous or omnivorous evolution in ancient birds, although a few groups of non-avian dinosaurs, such as Microraptor, also underwent convergent evolution, they still could not avoid the crisis of extinction.

Figure 3. Evolution of the internal microstructure of teeth in Cretaceous birds and small non-avian theropod dinosaurs (a-Troododon, b-Anchiornis, c, d-Microraptor, e-Unidentified enantiornithine, f-Neoavianus, g-Longwingornis, h-Huaornis). High-resolution synchrotron radiation microscopy images show that the porous dentin (IGS) in the teeth has disappeared in birds and Microraptor, providing evolutionary evidence of dietary shifts. (Image provided by Zhiheng Li)