On February 1, Wang Min, Zhou Zhonghe, and Zou Jingmei from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, along with Pan Yanhong from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology, reported in Nature Communications a discovery of an Early Cretaceous enantiornidian, *Cruralispennia multidonta*, dating back 130 million years. The discovery revealed that the pygostyle and tail feathers were independent of each other in the early evolution of birds, and also revealed a unique type of feather.

Enantiornithes are the most successful group of birds in the Mesozoic era, forming a sister group to ornithomorphs (all extant birds evolved from ornithomorphs). The newly discovered fossils are from the Huajiying Formation, dating back 130 million years. Although one of the oldest known enantiornithes, this new bird retains many advanced features, including two pairs of projections on the posterior margin of the sternum, reduced wingtips, and shortened fibula and pygostyle, clearly distinguishing it from other birds found in the same stratum. Furthermore, the new bird possesses 14 teeth in its lower jaw, the most in a known enantiornithe, revealing significant morphological differentiation that already existed in the early stages of enantiornithe evolution.

The most significant change in the evolution from dinosaurs to birds was in the tailbone. Unlike the long tailbones of dinosaurs, the tailbones of modern birds are significantly shortened, especially with the last few caudal vertebrae fusing into a pygostyle. In lateral view, the pygostyle of modern birds is plow-shaped, its surface covered with muscle and fibrous fat that controls the unfolding and closing of fan-shaped tail feathers, forming an important component of flight. Previously, such a plow-shaped pygostyle was only found in ornithopterygii, and fan-shaped tail feathers were also mostly found in ornithopterygii; conversely, in enantiornithines and other more primitive birds (such as Confuciusornis and Ephemeropteryx), the pygostyle has a simple, rod-shaped morphology, especially lacking a dorsal curve at the end, and its relative length is significantly greater than that of ornithopterygii. Therefore, their pygostyle is simply a result of tailbone shortening, and fan-shaped tail feathers are rarely found in these birds. Thus, researchers generally believed that the plow-shaped pygostyle and fan-shaped tail feathers evolved synchronously. However, the discovery of *Polydentate tibialis* challenges this view. The pygostyle of *Polydontidae* is significantly shortened, with a relative length similar to that of ornithoids. More importantly, the end of its pygostyle curves dorsally, forming a vomerine pygostyle identical to that of ornithoids. Researchers using discriminant analysis to construct the morphological space of Mesozoic bird pygostyles also confirmed that the pygostyle of *Polydontidae* is morphologically closer to that of ornithoids. However, *Polydontidae* does not possess fan-shaped tail feathers; instead, its tail feathers are non-flanked, indicating that the ornithoid pygostyle appeared in at least one enantiornithine group through parallel evolution, and the hypothesis of "co-evolution of vomerine pygostyle and fan-shaped tail feathers" needs to be reconsidered.

Researchers observed a peculiar type of feather on the tibia and tarsus of the bird *Pterygodon*. These feathers, approximately 12–16 mm long, are generally linear, but branch out into fine filaments at their tips. Researchers believe these fine terminal branches represent individual barbs, with the main parts of these barbs fused to form the rachis, branching only at the end. Bird hind limb feathers are primarily of two morphologies: vane-like and down-like; however, the hind limb feathers of *Pterygodon* differ from all known extant or fossil feathers, representing an extinct feather morphology in feather evolution—proximally wire-like part with a short filamentous distal tip (PWFDTs). Scanning electron microscopy observation of the *Pterygodon* feathers revealed that the chromoplast morphology of the tibia and tarsus feathers differed significantly from feathers on other parts of the body, and the geometry of the chromoplasts was correlated with their color, indicating that these tibia and tarsus feathers possessed different colors. The tibiae feathers of the multi-toothed tibiae feather bird clearly do not have an aerodynamic function, and their structure, which is different from down feathers, suggests that their heat insulation/insulation function is limited. Therefore, researchers speculate that such feathers may be used to attract mates, which is also corroborated by the different colors reflected by the chloroplasts.

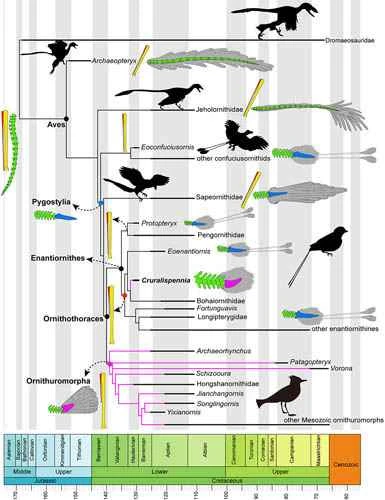

Furthermore, *Polydontidae* provides other important evolutionary information, such as the shortening of the fibula, representing the earliest appearance of this advanced feature. Microscopic observation of its skeleton suggests that *Polydontidae* could reach adulthood in about a year, unlike the slow growth pattern of other enantiornithines. Through phylogenetic studies of Mesozoic birds, *Polydontidae* is classified as a relatively advanced enantiornithine, inconsistent with its relatively ancient strata. Estimates of the divergence time of major lineages, due to the discovery of *Polydontidae*, suggest that the origin and divergence of major Early Cretaceous bird lineages occurred much earlier than previously thought.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Category B).

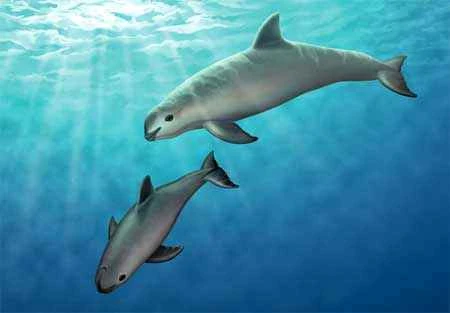

Figure 1. Comparison of the holotype fossil of *Cruralispennia multidonta* and the pygostyle of a Mesozoic bird (Image provided by Wang Min)

Figure 2. Feathers and chloroplasts of the multidentate tibiae, reconstruction of tibiae and tarsi feathers, and evolution of hind limb feathers in early birds (Image provided by Wang Min).

Figure 3. Phylogenetic tree of Mesozoic birds, illustrating the time of major lineage differentiation and the main evolution of the pygostyle and tibia and fibula (Image provided by Wang Min).

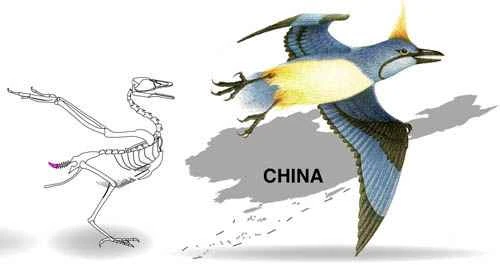

Figure 4. Reconstruction of the Multitoothed Taurid (Photos provided by Shi Aijuan and Wang Min)