The connection between horses and human history can be traced back 350 centuries, with the earliest records coming from cave paintings of wild horses dating from the Middle Paleolithic period in France and Spain, approximately 35,000 to 100,000 years ago. The domestication of horses occurred much later than the domestication of dogs; domesticated horses were only introduced from the Taban wild horses of Western Europe or Przewalski's horses of East Asia around 6,000 years ago. Since then, horses have played an extremely important role in human history.

Archaeopteryx

However, the history of the horse itself is much longer. Horse fossils have long been considered the most typical example of biological evolution because horses have preserved a rich fossil record over 58 million years of geological history, a record that continues to the well-known modern horse. As early as 1851, Sir Robert Owen of England recognized the linear evolutionary sequence from early equines to the modern horse, with their toes gradually changing from multiple to single, and becoming increasingly adept at running.

Eohippus appeared in the very early Eocene epoch, and was only the size of a small dog. Eohippus was agile and nimble, with four toes on its forefeet and three on its hind feet, possessing small hooves. However, only three toes on its forefeet were functional, classifying it as an odd-toed ungulate. Its limbs were long and slender, adapted for running, with its wrists and ankles lifted off the ground, resulting in almost vertical phalanges. It had a relatively arched back, a short tail, and a long, low skull that was quite primitive. Its teeth were low-crowned with conical cusps, but the structure of its premolars had not yet become similar to that of molars. Eohippus lived in tropical forests and swamps, feeding on tender leaves of shrubs. During the Eocene, Eohippus was distributed across the Americas, Asia, and Europe, connected by land bridges. The earliest known Eohippus specimens came from England, and later, more well-preserved specimens were discovered in various parts of the western United States. With the end of the early Eocene, the Eohippus went extinct in the Old World. From then on, the evolution of horses was limited to North America, and the horses that appeared on other continents later spread from North America.

Reconstruction of a three-toed horse

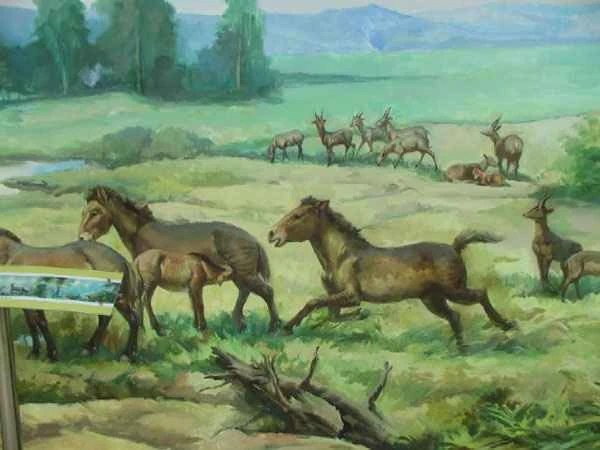

During the Oligocene epoch, 40 million years ago, Oligocene horses appeared in North America, living in arid, shrub-covered environments. Oligocene horses were larger than Eohippus, resembling modern lambs. Their backs became straighter and more rigid, and their legs were longer. Their little toes disappeared, leaving only three toes on each foot, with the middle toe significantly enlarged, but all toes were in contact with the ground. Their cheek teeth were still low-crowned, but except for the first premolar, the rest had become like molars—a phenomenon known as premolarization. The strong ridges on their cheek teeth made them highly effective tools for cutting leaves. Steppe horses evolved from Oligocene horses and lived during the Miocene epoch, 18 million years ago, by which time their bodies had grown to the size of modern ponies. The ancient steppe horse still had three toes on its front and hind feet, but it relied only on the middle toe to walk, while the lateral toes on both sides had degenerated to the point of being almost useless; its face became longer and its lower jaw became higher; its teeth were wear-resistant high-crowned teeth, which made it easier to eat widely distributed herbaceous plants.

Pliocene horses appeared during the Pliocene epoch, about 5 million years ago, and had grown to the size of a modern medium-sized horse. Pliocene horses were an advanced type of horse, with their fore and hind feet having become true single-toed, walking only on the strong middle toe, with well-developed hooves, while the lateral toes had degenerated to mere traces, hidden in the skin of the upper part of the foot; the crowns of their cheek teeth had become higher.

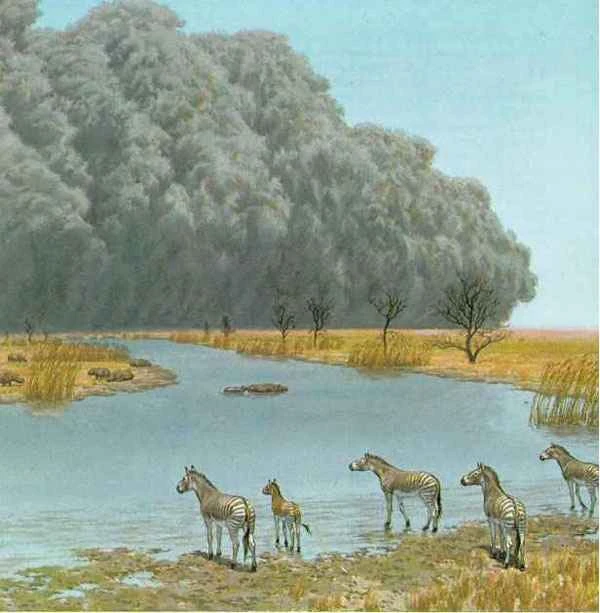

The true horse evolved from the Pseudohorus about 4 million years ago, and its body shape was already similar to that of the modern tall horse. Its limbs were highly specialized: the humerus and femur were short, the radius and tibia were long, the ulna and fibula were reduced, the only remaining toe was well-developed, the metacarpals were very long, while the phalanges were relatively short; its cheek teeth had high crowns and finely folded enamel, while the first premolar had degenerated to a very small size or even disappeared completely. The true horse spread to other continents in the early Pleistocene and was widely distributed in Asia, Europe, Africa, and South America during the Quaternary period.

Over 58 million years of evolution, horses have continuously changed various aspects of their bodies: they have become larger, their legs have lengthened, their lateral toes have atrophied while their middle toes have strengthened, and their backs have straightened and hardened; their premolars have become more like molars, their incisors have widened while their cheek teeth have increased in height, and the crowns of their teeth have become more complex; their skulls and mandibles have become more prominent, their faces have lengthened, and their brains have become larger and more complex.

The above describes the evolutionary history of horses from Eohippus to the modern horse; however, this is only a simplified outline. In reality, horse evolution is much more complex. Between Eohippus and Oligocene, there were mountain horses and sub-horses; between Oligocene and steppe horses, there were Miocene and parahorns; and Pliocene further evolved into the South American horse, which is distributed in South America. Early horse evolution was indeed relatively simple and linear, a phenomenon known as "linear evolution," and the horse is often considered the most typical example of this evolutionary path. With the spread of the Miocene steppes, horses that graze on grass appeared under adaptive radiation, while those that graze on tender leaves continued to exist, thus achieving the greatest diversity of horses in the Miocene. Various side branches of horses emerged in the middle and late Tertiary, some with progressive traits, while others remained primitive. Two of the most important side branches in horse evolution, *Equus angustifolius* and *Equus tritodactylus*, appeared in the Miocene. They are not direct ancestors of modern horses, but the fossils of these two genera are abundant and widely distributed, holding significant scientific importance for the division and correlation of Miocene and Pliocene strata.

Angel horses were similar in size to modern ponies and lived in forests. During the Miocene epoch, they were distributed across North America and Eurasia. They had low-crowned teeth and three toes on both their fore and hind feet.

The three-toed horse was agile in structure and similar in size to the angel horse. Of course, it also had three toes, a primitive trait. Unlike the angel horse, the three-toed horse had high-crowned cheek teeth with complex enamel folds, an advanced trait. The three-toed horse was widely distributed in North America, Eurasia, and Africa during the Middle and Pliocene, and finally went extinct in the Middle Pleistocene, leaving no descendants. In China, the three-toed horse was one of the most representative mammals from the Late Miocene to the Early Pleistocene.

The South American horse is also an evolutionary branch that appeared at the end of the Pliocene epoch. It originated in South America when the ancestors of the Pliocene horse entered the southern continent after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama. The South American horse was large in size but had relatively short legs. It lived during the Pleistocene epoch and became extinct before the end of the Ice Age.

After a period of dramatic evolution and complex adaptive radiation, the history of the horse calmed down in the late Pleistocene. In the Americas, the main battleground for equine evolution, horses became completely extinct 8,000 years ago, only to be reintroduced to the continent by Spanish colonists in 1519. Today, only the genus *Equus* exists within the Equidae family, whereas at its peak, 13 genera coexisted. All six wild species of modern horses are rare: three species of zebras (mountain zebra, plains zebra, and slender zebra), two species of wild asses (African wild ass and Asian wild ass), and one species of wild horse (Przewalski's horse).