Recently, the Nature sub-journal *Nature Ecology & Evolution* published a study independently conducted by the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, on the independent evolution of skulls and bodies in early birds. Li Zhiheng and Wang Min are co-first authors, with Wang Min as the corresponding author. *Nature Ecology & Evolution* is a Q1 journal in the Biology category of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, with an impact factor of 15.46.

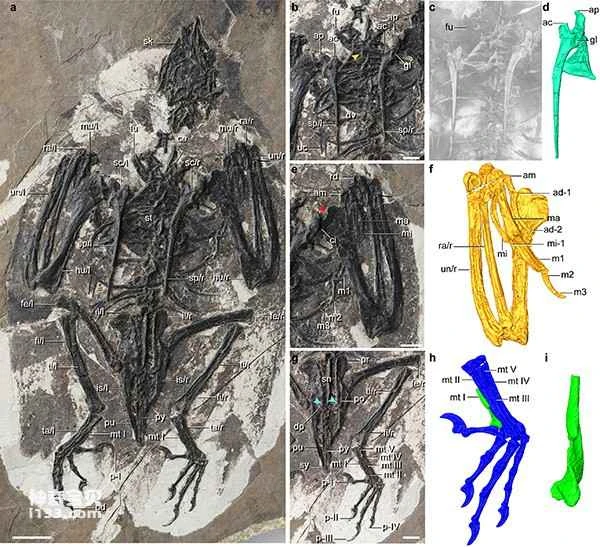

The Mesozoic Era records how birds evolved from dinosaurs and developed unique physical characteristics. The diversity of the avian lineage during this evolutionary stage was primarily dominated by ornithodonts, consisting of enantiornithines and ornithomorphs. These ornithodonts had already evolved many morphological features similar to modern birds, showing significant morphological differences from the most primitive birds (Archaeopteryx). Non-ornithodonts, which occupy an intermediate evolutionary position (hereinafter referred to as basal birds), provide important information for bridging this gap. However, for a long time, research on the early differentiation of basal birds has been limited by fossil discoveries. The newly discovered bird belongs to a new genus and species (Figure 1) of the basal bird family Jinguofortisidae of the Jehol Biota (135-120 million years ago). Researchers have named it *Cratonavis zhui*: "鸷" (zhui) means fierce bird, taken from Qu Yuan's poem *Li Sao*—"The fierce bird does not flock with others; this has been the case since ancient times." The genus name "cratonavis" is derived from the National Natural Science Foundation of China's Basic Science Center project "Craton Destruction and Terrestrial Biological Evolution" (a large-scale interdisciplinary project exploring the intrinsic connection between biological evolution and the destruction of the North China Craton). The species name is dedicated to Academician Zhu Rixiang, whose team has conducted extensive and important research on the mechanisms of the destruction of the North China Craton.

Cratonosaurus shares a similar skull morphology with theropod dinosaurs, particularly retaining the structure of the bitemporal fenestrae of primitive archosaurs—the superior and inferior temporal fenestrae are independent of the orbits and separate from each other, the pterygoid has enlarged quadrate ramus, and the vomer is large. These primitive features indicate that Cratonosaurus did not evolve the skull mobility found in most birds, i.e., the maxilla moves independently of the cranium and mandible. In contrast, the postcranial skeleton of Cratonosaurus already possesses many advanced avian features, such as an ossified sternum, elongated forelimbs, shortened tailbone, and opposing claws, demonstrating modular evolution of the skull and body, with the skull, especially the temporal and palatal regions, showing relatively conservative evolution.

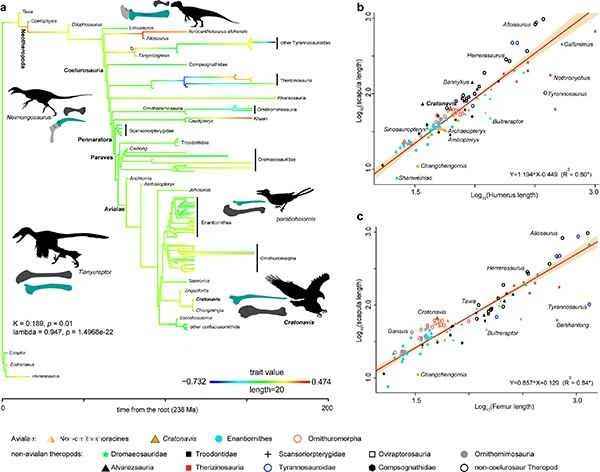

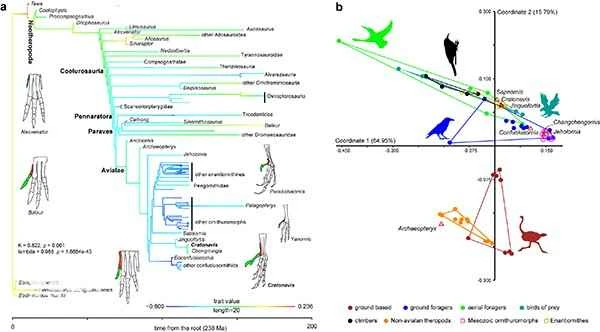

Cratonroth is most notably characterized by its unusually long scapula and first metatarsal (the innermost bone of the foot). Researchers used comparative cladistic methods to trace the dynamic trajectory of these two bones during dinosaur-avian evolution (Figure 2). The scapula is a crucial component of avian flight structure, and its morphology varies significantly among birds with different flight modes. Researchers found that the scapula's length changes more readily in theropod dinosaurs than in birds, and its independent elongation in Cratonroth may be an attempt to adapt to flight, as the elongated scapula increases the attachment area for muscles controlling downward wing flapping. The relative length of Cratonroth's first metatarsal far exceeds that of other birds and most dinosaurs. In dinosaur-avian evolution, the first metatarsal shows a trend of shortening; for example, the relative length ratio of the first metatarsal in birds is much smaller than in primitive theropod dinosaurs, while the proportion of the first metatarsal in birds was established at the beginning of their divergence. The elongation of the first metatarsal in Cratonroth is a result of independent evolution. This conclusion can also be confirmed by changes in the phylogenetic signals of the first metatarsal: its influence from phylogenetic relationships is higher in theropod dinosaurs, but decreases when approaching paraaviridans (Figure 3). Using ecological axis analysis, combined with the large first toe and curved claws, researchers suggest that the abnormal growth of the first metatarsal may be related to the raptor-like ecological habits of Cratongarh. The unique scapula and metatarsals of Cratongarh demonstrate that, under the dynamic influence of ontogeny, natural selection, and opportunities for ecological function, some seemingly evolutionarily conserved bones have "broken free from constraints" and undergone evolutionary changes.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Basic Science Center Project "Craton Destruction and Terrestrial Biological Evolution", the Chinese Academy of Sciences Frontier Science Key Research Program "From 0 to 1" Original Innovation Ten-Year Selection Project, and the Tencent Exploration Award.

Paper link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-022-01921-w

Figure 1: Homotype specimen of Cratonavis zhui (Photos provided by Wang Min and Li Zhiheng)

Figure 2: Evolutionary trajectory of the scapula during the dinosaur-bird evolution (Image provided by Wang Min)

Figure 3: Evolutionary trajectory of the first metatarsal bone during the dinosaur-bird evolution (Image provided by Wang Min)

Figure 4: Reconstruction of *Zhu's Craton Falcon* (drawn by Zhao Chuang)