In 2019, Nature published the research findings of Wang Min, Zou Jingmei, Xu Xing, and Zhou Zhonghe from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, as a cover article: Jurassic scansorornis reveal the evolution of membranous wings in dinosaurs, demonstrating a large number of unexpected attempts to adapt to flight in the dinosaur-bird evolutionary process, which corresponded to the evolution of significantly different bone-epidermal derivative combinations.

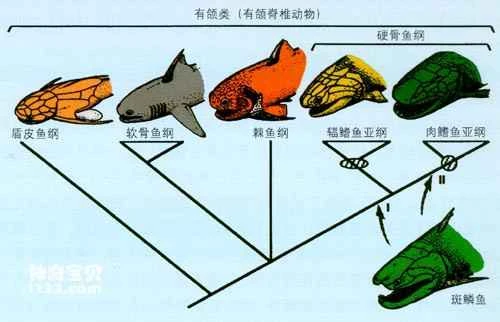

In the long evolutionary history of vertebrates, pterosaurs, birds, and bats independently evolved flight structures with vastly different morphologies. Compared to the incomplete fossil record of pterosaurs and bats, significant progress has been made in answering the important scientific question of the origin of bird flight, thanks to the continuous discovery of feathered dinosaur and early bird fossils, especially the Yanliao Biota of the Middle and Late Jurassic and the Jehol Biota of the Early Cretaceous in China. The discovery of the Scansoriopterygidae reveals "an incredible journey to conquer the blue sky." The Scansoriopterygidae are the most bizarre group in the dinosaur family, living in the Middle to Late Jurassic. To date, only three genera and species have been discovered: *Epidendrosaurus ningchengensis*, *Epidexipteryx hui*, and *Yi qi*. The scanspikyosaurs are morphologically unique, with features such as a high-set skull, slender limbs, an elongated third finger (the outermost finger), an ancient 2-3-4 finger system, and a shortened tailbone, making them appear as a "hybrid" of dinosaurs and birds. They were once considered theropod dinosaurs most closely related to birds. However, the aforementioned specimens are either incomplete or belong to juvenile individuals, making many morphological features difficult to observe, thus obscuring their position on the evolutionary tree. The *Illypterosaur*, named by Xu Xing et al. in 2015, adds further mystery to this group. *Illypterosaur* had wing membranes attached to its forelimbs and a rod-like long bone, a structure without a corresponding homolog in other dinosaurs (including birds). Therefore, *Illypterosaur* has been reconstructed as having membranous wings similar to pterosaurs, enabling gliding. However, only one *Illypterosaur* specimen exists, and it is incomplete, so the structure of the rod-like long bone and wing membrane remains controversial.

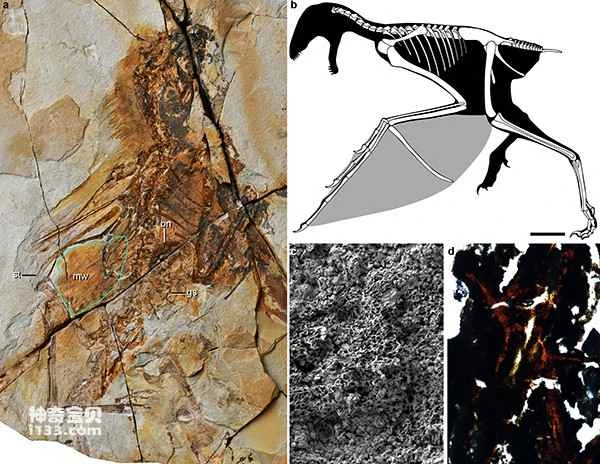

In 2017, Zhou Zhonghe and his team from the Center for Basic Science discovered a new fossil during an expedition through Late Jurassic strata in Liaoning Province. After a year of laboratory repair, experimentation, and comparative studies, the research team concluded that it represents a new type of scansoriopterygii and named it *Ambopteryx longibrachium* (meaning a hybrid of pterosaur-like membranous wings and dinosaur characteristics). *Ambopteryx longibrachium* was discovered in the Haifanggou Formation of the Early Late Jurassic of the Yanliao Biota (approximately 163 million years ago). Its holotype is the most complete known scansoriopterygii fossil, providing a wealth of morphological and ecological information. *Ambopteryx longibrachium* was approximately 32 cm long and weighed about 306 grams. It differs significantly from other scansoriopterygii in the proximal articular surface of the humerus, the morphology of the fingers and pelvic girdle, and possesses a pygostyle similar to that of primitive birds. This shortened tailbone further shifts the body's center of gravity forward, aiding in stability during flight/gliding. More importantly, researchers discovered rod-shaped long bones and wing membranes (containing chloroplasts) similar to those of *Qiyiosaurus* in *Hunyuanosaurus*. This new discovery provides definitive evidence for the presence of rod-shaped long bones and wing membranes in scansornis. *Hunyuanosaurus* also contained gastroliths and what appears to be partially undigested bony stomach contents, the first such evidence related to diet found in scansornis, leading researchers to speculate that it was omnivorous.

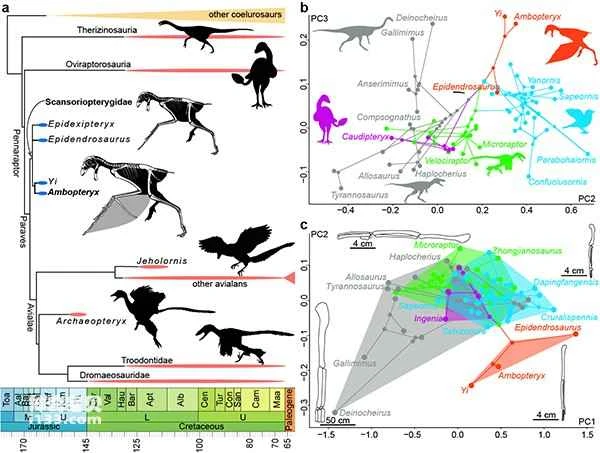

The forelimbs of *Hunyuanlong* were abnormally long, even exceeding those of most birds in the Mesozoic Era. Researchers, when comparing dinosaur forelimbs, discovered a very peculiar proportion in the forelimbs of *Scanthopterygii*. Could this difference be related to the appearance of wing membranes? To confirm this hypothesis, Wang Min et al. used principal component analysis (PCA) based on phylogenetic relationships to discuss the evolution of limb length in Mesozoic coelurosaurs (including birds), particularly focusing on significant changes near the origin of flight. Phylogenetic PCA removes kinship relationships from traditional PCA, maximizing the independence of sampling points while restoring the characteristic states of ancestral nodes, thus revealing the evolutionary trends of different groups. The results showed that forelimb lengthening began with paraaviryns (the broadest group including all birds but excluding oviraptorosaurs), but only *Scanthopterygii* showed a lengthening approaching that of Mesozoic birds, a degree never achieved by other non-ornidosaur dinosaurs. The elongation of the forelimbs in scansornis primarily stems from the humerus and ulna; in birds, dromaeosaurids, and troodonts, it is the elongation of the metacarpals, and these groups all possess flight feathers in their forelimbs. Researchers believe that scansornis used elongated humerus and ulna, the third finger, and rod-shaped long bones to attach membranous wings, while birds, dromaeosaurids, and troodonts required longer metacarpals to attach flight feathers, demonstrating two distinct flight modes—"membranous wings and short metacarpals," and "feathered wings and long metacarpals"—that significantly altered the forelimb structure.

All known scansoriopterygii lived in the Late Jurassic, and similar membranous wings did not appear in Cretaceous dinosaurs. Wings composed of flight feathers appeared in the Late Jurassic and continued into the Cretaceous, eventually evolving into the wings of birds, making them the most diverse extant tetrapods. The unique flight structure of scansoriopterygii represents a brief attempt at flight evolution.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Basic Science Center Project (Craton Destruction and Terrestrial Biological Evolution), the Excellent Young Scientists Fund Project, the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the State Key Laboratory of Lithosphere Evolution (North China Craton Destruction and Yanliao-Jehol Biota Evolution).

Original link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1137-z

Figure 1. Cover of the current issue of *Nature*: A Jurassic dinosaur with membranous wings discovered by the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology.

Figure 2. a, Holotype specimen of *Hun Yuan Long*; b, Skeletal reconstruction; c, Membranous wing membrane chloroplasts; d, Histological section of bony gastric contents. bn, Bony gastric contents; gs, Gastric bezoar; mw, Membranous wing membrane; st, Rod-shaped long bone. (Photo provided by Wang Min)

Figure 3. Mesozoic coelurosaur phylogeny and limb bone evolution: At the origin of flight, different groups of paraavidins showed different forelimb elongation processes: scanspinosaurs elongated the humerus, combined with a third finger and a rod-shaped long bone to attach membranous wings; while dromaeosaurids, troodontids, and birds elongated the metacarpals to attach feather-like wings (Image provided by Wang Min).