A joint team led by Zhu Min from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Alberg from Uppsala University, Sweden, has made a major breakthrough in the study of vertebrate jaw evolution. In the latest issue (October 21, 2016) of the journal *Science*, they reported on a 423-million-year-old Silurian placoderm, *Qilinyu rostrate*, which fills the morphological gap between the bony fish-like full jaw and the placoderm-like protojaculate jaw. For the first time internationally, they proposed the theory that the maxilla, premaxilla, and dentary bones of full-jawed placoderms and bony fish are homologous to the jaw plates of protojaculates, tracing the human jaw back to the most primitive jawed vertebrate—the protojaculate.

This crucial breakthrough "cleared a major blind spot in our understanding of vertebrate jaw evolution," according to a commentary titled "First jaws" by Professor John Long, President of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and Professor at Flinders University, Australia, published in the same issue of *Science* magazine in its Perspective section. The commentary states that the series of discoveries from China "is changing the understanding that placoderms are extinct, and that placoderms are key to understanding how vertebrate body structures evolved step by step in the distant past."

Armored rulers of the fish age

The Devonian period (approximately 419 to 359 million years ago) is known as the "Age of Fishes." During this time, aquatic vertebrates, especially jawed vertebrates with upper and lower jaws, experienced an explosive evolution. A diverse array of fish filled the waters of the Earth, with placoderms, whose bodies were covered in large bony plates, dominating the field. In terms of species numbers, individual numbers, and morphological diversity, they were the undisputed rulers of the Age of Fishes. By the late Devonian period, one of the most famous prehistoric super-predators had evolved—Dunkleosteus. Dunkleosteus could reach lengths of up to 10 meters, its jaws armed with blade-like sharp bony plates, possessing a powerful, hydraulically shearing bite force, feeding on various large fish in its habitat.

However, with the end of the fish age, Dunkleosteus and other placoderms suddenly went extinct at the end of the Devonian period, 359 million years ago. The habitat they left was divided among more advanced bony and cartilaginous fish. Cartilaginous fish include today's sharks, rays, and chimaeras, while bony fish split into two, evolving into ray-finned fish and lobe-finned fish. They became the conquerors of today's waters and land, respectively. There are now about 25,000 species of ray-finned fish, including most of the diverse fish species we see today. Although lobe-finned fish declined in the water, one branch ventured onto land, giving rise to all terrestrial vertebrates, including humans.

For years, paleontologists have tried to understand the evolutionary relationships between these groups, and thus to clarify the lineage of human ancestors. How did we evolve from those long-extinct, strangely shaped fish-like ancestors? Early fish fossils have mostly been found in Devonian strata, by which time the major groups had already diverged, lacking transitional fossils representing intermediate stages. Tracing back to the Silurian period, before the age of fish, the evolutionary history of vertebrates has become obscured. For a long time, scientists could only attempt to reconstruct this history through fragmented materials, like blind men feeling an elephant. Finding a completely preserved ancient fish in Silurian strata is the "holy grail" that paleontologists worldwide have been dreaming of.

The Lost Kingdom of Ancient Fishes in the Silurian Period

During the Silurian and Devonian periods, southern China was an isolated continent adrift near the equator. Yunnan was located in the southern part of this continent. Rivers meandered out from the barren, exposed mountains in the center of the continent (at that time, plants had not yet invaded the interior), flowing into the ocean at a place equivalent to modern-day Qujing in eastern Yunnan. They brought abundant nutrients, nurturing a thriving ecosystem in the estuaries and bays, a "kingdom" of fish: crinoids and brachiopods thrived near the reefs, providing hiding places for fish; schools of small fish diligently filtered mud and sand at the bottom of the water, or searched for soft food such as worms; fierce large predatory fish patrolled overhead... Over tens of millions of years, countless strange fish lived, reproduced, and died here, their remains sinking to the bottom, encased in mud and sand, with a few fortunate enough to become fossils.

Over four hundred million years have passed, and with the changing of the sea and land, the ancient bay has long since transformed into the undulating mountains and scattered fields of eastern Yunnan today. Through long and complex geological processes, the ancient seabed sediments formed layers upon layers of strata, with continuous sediments spanning the Silurian and Devonian periods now exposed here. Within this vast geological record lies precious information about the evolution of life, information previously unknown to humankind.

As early as the last century, Chinese scientists discovered a variety of unique primitive bony fish in the Early Devonian strata of eastern Yunnan. However, by then, the age of fish had reached its zenith, and the major groups had long since diverged. These discoveries could only provide some indirect clues for studying the lineage of human aquatic ancestors. Could the "holy grail" of ancient fish research be found in the even earlier Silurian strata? After decades of tireless searching, in 2007, Zhu Min's team finally discovered exquisitely preserved fish fossils in the Silurian strata near the Xiaoxiang Reservoir in Qilin District, Qujing, Yunnan. This is the Xiaoxiang Fauna, the only one in the world to have completely preserved Silurian jawed vertebrate fossils. The lost ancient fish "kingdom" of the Silurian has seen the light of day again.

However, the diversity of the Xiaoxiang fauna far exceeded Zhu Min and his colleagues' initial expectations. After several years of continuous excavation, they discovered that this ancient fish "kingdom" had once flourished, and the fossils discovered alone may represent about twenty or thirty entirely new fish species. These ancient fish were not only ancient but also had very strange shapes, and similar species could not even be found in other parts of the world. They belonged to some completely new groups that had never entered the scientific community's field of vision before.

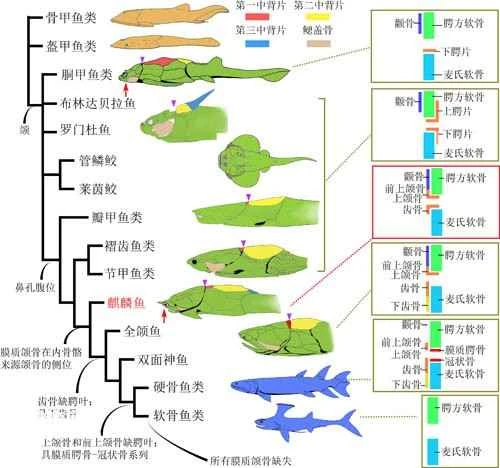

Placoderms are a major component of the Xiaoxiang fauna. However, most of these placoderms belong to a unique, previously unknown lineage that only existed in southern China during the Late Silurian period, after which they mysteriously disappeared from the course of evolution. Zhu Min et al. named them "holognathous placoderms." Their anterior bodies were covered with large bony plates, their shape not much different from other placoderms, but their jawbones exhibited a typical bony fish pattern, consisting of a complex series of bony plates forming a "holognathous jaw." These placoderms with bony fish jawbones, much like feathered dinosaurs confirming the origin of birds, clearly demonstrate that bony fishes evolved directly from placoderms, completely overturning previous understandings of the evolutionary relationships between major groups during the fish era.

In 2013, Zhu Min et al. reported on *Arthrochelys primordicus*, the first member of the holochelyspidae, in the British journal *Nature*, which immediately attracted widespread attention. *Arthrochelys primordicus* was described as "a jaw-dropping fish" and hailed as "one of the most important fossil discoveries of the past century." However, soon after, more holochelyspidae fossils were discovered, suggesting that this group once "held sway over its own territory," thriving despite its limited lifespan and range, occupying diverse ecological niches. The recently reported *Lycodon longsnospermus* possesses characteristics that clearly classify it as a holochelyspidae, yet its morphology differs significantly from the previously discovered *Arthrochelys primordicus*, fully demonstrating the diversity of holochelyspidae.

The name "Qilinfish" is a double entendre, referring both to its discovery location in Qilin District, Qujing City, and implying that it, like the mythical Qilin (a mythical creature with a dragon's head, deer antlers, a deer's body, and an ox's tail), embodies characteristics of multiple groups. The fossils of Qilinfish are exquisite; the large bony plates encasing its body have perfectly preserved their shape even after more than 420 million years. Its head resembles both a dolphin and a sturgeon, with a protruding, flat snout at the front followed by a raised "forehead," and its mouth and nostrils located on its ventral side. Its body is long and box-shaped with a flat bottom. In the Silurian bays of Qujing, they likely gathered in groups, swimming slowly on the seabed, using their snouts to stir up mud and sand, searching for worms and organic debris, relying on their bony plates and camouflage to defend against predators.

The Qilin fish is not large, measuring about 20 centimeters in length when alive, and its appearance is not particularly striking. However, Zhu Min and others discovered that its jawbone morphology remarkably preserves an intermediate stage of evolution, providing a crucial clue to an important question that had previously remained unanswered by placoderms: Are the jawbones of bony fishes and placoderms homologous? If so, how did the former evolve from the latter?

The evolution of the jawbone from fish to humans

The mouth, with its upper and lower jaws, is an important organ for humans to eat, breathe, and communicate, and is a common feature of all jawed vertebrates, from fish to humans. The structure of the human upper and lower jawbones may seem simple, but in reality, they have undergone a tortuous and complex evolutionary process to finally become what they are today.

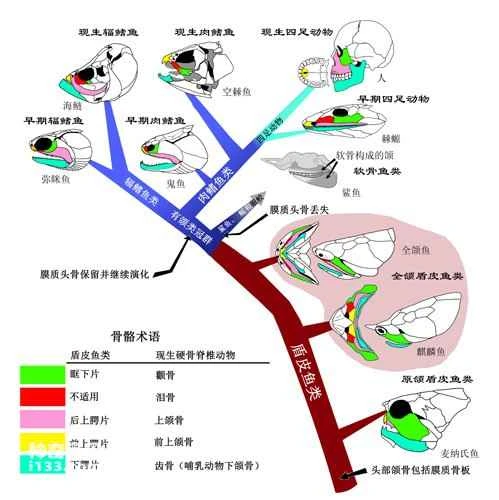

The upper and lower jaws evolved from the gill arches and were originally composed of cartilage. Over the long course of evolution, bone plates (membranous bone) from the body surface gradually invaded the upper and lower jaws, reinforcing and replacing the function of the original jawbones. It was the addition of these later jawbones that gave rise to the complex oral structures of teleost fish, such as the elongated mouths that can suck in food, the diverse beaks of birds, and the large tusks of elephants. Ultimately, this also shaped the human jawbone, while the original cartilaginous jaw components have long since retreated into the ear, becoming the ossicles and forming part of the auditory system.

Human jaws can be traced relatively clearly back to our primitive bony fish ancestors. Three main pairs of jaws—the premaxilla (a remnant in humans), maxilla, and dentary—are located at the edge of the mouth, adjacent to other facial bones. In primitive bony fish, these marginal jaws also contained a series of jawbones, including the vomer, pterygoid, and coronoid bones, which once functioned in biting, but have disappeared or regressed into the nasopharynx in humans over time. We refer to this more complex jaw structure, composed of many bony plates, in bony fish as a "complete jaw state."

So how did the full jaw evolve? Since this jaw pattern has not been found in any major groups other than bony fishes, this question has remained unanswered. The jaws of cartilaginous fishes are entirely composed of cartilage, without any membranous bone reinforcement; while the jaws of typical placoderms like Dunkleosteus are called "protojaculate," although they have three pairs of membranous plates—the premaxillary, postmaxillary, and mandibular plates—located inside the oral cavity and not connected to other facial bones.

The existence of the initial holognathous fish has definitively proven that bony fishes evolved from a branch of placoderms. So, is there an evolutionary connection between the three pairs of jaw plates in placoderms and the jawbones of bony fishes? Positionally, these three pairs of plates should correspond to the medial jawbones of bony fishes, but the latter number far more than three pairs. Therefore, the previously proposed holognathous origin theory posits that the three pairs of medial jaw bones in placoderms were lost during the evolution from placoderms to bony fishes, and that all jawbones in the holognathous state, including the lateral and medial series, evolved anew.

Clearly, this theory requires significant changes and reorganization of the jawbone, while in most cases, evolution tends to be a conservative, gradual process of patching and repair. In contrast, the second possible theory is more straightforward: the three pairs of medial jaw bones in placoderms moved outward, becoming the three pairs of lateral marginal jaw bones in the full jaw state, while bony fish simply evolved a new series of medial jaw bones.

Holojawfish have evolved a nearly complete jawbone structure characteristic of bony fishes, which is completely different from the jaws of other placoderms, leaving a significant evolutionary gap. To make a choice among the above theories and answer the question of where the holojaw state came from, a jaw that is even more primitive than that of Holojawfish is needed.

Incomplete full jaw

In many respects, the morphology of *Qilinyu* is more primitive than that of *Halostoma*. Could it answer questions that *Halostoma* couldn't? Zhu Min and others conducted high-precision CT scans on *Qilinyu* fossils and carefully reconstructed each bone into a three-dimensional model in a computer. After repeated comparative studies, they discovered that *Qilinyu*, like *Halostoma*, already possessed a maxilla composed of the maxilla and premaxilla. However, *Qilinyu* had not yet evolved the series of bony plates covering the bottom of the lower jaw, which is present in both *Halostoma* and bony fish. Its lower jaw consisted of only a simple mandible, which still retained a clearly retracted portion into the mouth, unlike *Halostoma* and later bony fish, where only a narrow occlusal surface remained in the mouth. The jawbone morphology of *Qilinyu* is indeed between that of *Halostoma* and other more primitive placoderms; it possessed an "incomplete full jaw."

This "incomplete full jaw" reveals an intermediate state in the early evolution of the jaw: the jaw of the *Qilinus* had departed from the primitive pattern of placoderms and entered a new evolutionary stage, with membranous bony plates beginning to extend outwards, covering and reinforcing the jaw, but not yet reaching the perfection of the full-jawed fish. This further reveals the evolutionary history of the full-jawed pattern, supporting the second theory mentioned above regarding how the full-jawed pattern evolved, and establishing the homology between the maxilla, premaxilla, and dentary bones of bony fish and the three pairs of jaw plates of placoderms. The human jaw can be traced not only to bony fish and full-jawed fish, but also to our even more ancient ancestors—the proto-jawed placoderms.

Throughout the history of life's evolution, major evolutionary events are often leaps in time, fleeting on a geological scale, and therefore difficult to preserve in the fossil record, resulting in numerous morphological gaps and evolutionary gaps between species. The older the era, the more numerous and larger these gaps and gaps become. Occasionally, we are fortunate enough to find transitional fossils that fill these gaps and gaps, opening rare windows that allow humanity to glimpse the mysteries of evolution. As more discoveries surface in the lost ancient fish kingdom of Yunnan during the Silurian period, many more fragments of this evolutionary epic remain to be filled.

This achievement was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Key Program), and the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The field excavation was supported by governments at all levels in Qujing City, Yunnan Province.

Figure 1. Photographs of the holotype specimen of the long-snout gorilla (IVPP V20732): dorsal view (A), ventral view (B), and lateral view (C) (Photos provided by Zhu Min)

Figure 2. Ecological restoration diagram: a unicorn swimming in the ancient Silurian ocean 423 million years ago (illustrated by Yang Dinghua).

Figure 3. Evolutionary path of membranous jawbones in vertebrates (illustrated by Brian Choo)

Figure 4. A simplified phylogenetic tree illustrating the evolutionary sequence of membranous jaws from the prognathous pattern in placoderms to the full-jawed pattern in bony fishes. Brown silhouettes represent jawless jawed stem groups (platefish), green silhouettes represent jawed stem groups (platorodactyls), and blue silhouettes represent jawed crown groups. Red arrows indicate the location of the mouth, and brown arrows indicate the boundary between the head and the carapace. (Image provided by Zhu Min)