The asteroid impact wiped out the dinosaurs and most other species on Earth, but mammals survived this catastrophe. So how did these tiny and fragile creatures, including our mammalian ancestors, survive this apocalypse?

This was one of the most tragic days in Earth's history. A furry little animal scurried in terror through a hellish world shrouded in darkness, volcanic ash, and deadly heat, searching for food to survive on the scorched earth. After catching an insect, it immediately fled in panic to its underground shelter. Surrounding the little animal were the massive bodies of dead or dying dinosaurs, behemoths that had threatened the survival of the poor mammals for generations.

This is the hellish scene in the first few weeks or months after an asteroid 10 kilometers in diameter, with the power equivalent to more than a billion nuclear bombs, struck the coast of what is now Mexico. This cataclysmic impact ended the Cretaceous period and heralded the beginning of the Paleocene, a time when global forests were ablaze, massive tsunamis ravaged coastlines, and hot, vaporized rocks, volcanic ash, and dust were propelled miles into the atmosphere.

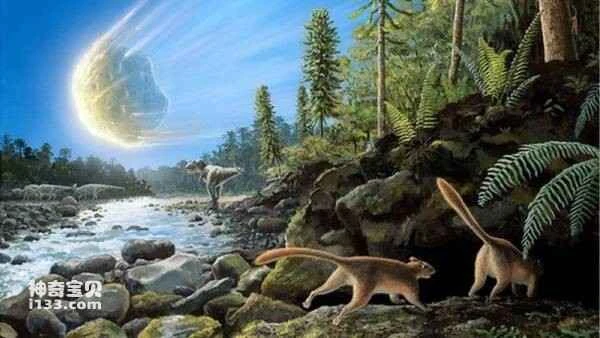

But life did survive in this devastated world. Among the survivors was the earliest known primate, the Purgatorius, a mammal that looked like a hybrid of a shrew and a squirrel. The Purgatorius population would certainly have declined after this global mass extinction, but fortunately, the species was preserved and can continue to reproduce.

This is what life was like for early mammals after an asteroid impact wiped out three-quarters of the Earth's species at the time. In terms of the magnitude of the extinction event, only the Permian-Triassic extinction event 252 million years ago, also known as the Great Dying, surpassed this asteroid impact. The Great Dying caused the extinction of 95% of marine life and 70% of terrestrial life, but the process was extremely slow, taking up to 60,000 years, unlike the sudden catastrophe of the asteroid impact.

An asteroid impact caused the extinction of the dinosaurs.

The asteroid impact that ended the Cretaceous period also wiped out famous dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus Rex and Triceratops, as well as the lesser-known but rather bizarre Anzu, known as the "chicken from hell." Hadrosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and other armored dinosaurs also went extinct. All of these dinosaurs were now extinct.

During the Late Cretaceous period, in the shadow of these colossal giants that dominated the Earth, small mammals like the Purgatorius lived in a position of ecological insignificance, much like rodents today. But how did these seemingly fragile creatures, including our human ancestors, miraculously survive this apocalypse?

The earliest known primate, the Purgatorius, was one of the survivors of the asteroid impact mass extinction. (Credit: Science Photo Library)

This is precisely the topic that Steve Brusatte, author of *The Rise and Reign of the Mammals*, and his colleagues at the University of Edinburgh have been researching.

Brusat emphasized that the day the asteroid struck Earth would have been a catastrophe for all life on Earth, including mammals, birds (i.e., bird dinosaurs), and reptiles. Brusat stated, "This was no ordinary asteroid; it was the largest asteroid to hit Earth in at least the last 500 million years. Mammals would have nearly been wiped out like the dinosaurs."

However, many mammal species did indeed disappear in this unprecedented natural disaster. Sarah Shelley, a postdoctoral researcher in mammalian paleontology at the University of Edinburgh, said that mammal diversity was already astoundingly rich in the Late Cretaceous period. She said, "Many mammals were small animals that lived in trees or caves and ate insects."

However, not all mammals are insectivorous. There was also a mysterious multituberculate mammal, named for the distinctive tubercles on its teeth. Shelley said, "This mammal had blocky teeth with many small bumps, and the front of the teeth was blade-like, looking like a saw. They ate fruits, nuts, and seeds."

There were also carnivorous mammals at the time, one of the largest being Didelphodon, a marsupial weighing about 5 kilograms, roughly the size of a modern domestic cat. Shelley said, "Judging from the skull and teeth anatomy, Didelphodon had a very strong bite force, capable of crushing bones, so it must have been a carnivore."

Brusat said that after the asteroid impact, most species of mammals in the Late Cretaceous period disappeared, with about 90% of mammals going extinct. However, this actually gave the surviving animals an unprecedented opportunity.

Brusatte said, “You can imagine that one of our tiny ancestors, only the size of a mouse, a timid little thing hiding in the shadows, survived this moment in Earth’s history. When the disaster was over, you emerged and suddenly found that all those terrible big guys like Tyrannosaurus Rex and long-necked dinosaurs had disappeared, and the whole world was open to you.”

This mass extinction created conditions for a large number of diverse new species, ultimately leading to blue whales, cheetahs, dormice, platypuses, and of course, humans.

Dinosaurs went extinct after an asteroid impact (Credit: Getty Images)

First, it's important to note that after the impact, forests around the world were consumed by wildfires, the sky was filled with smoke and dust, blocking out sunlight and preventing plants from photosynthesizing. As Brusatte put it, Earth's ecosystem collapsed "like a house of cards." The Earth's surface temperature became hotter than an oven due to a violent heat pulse with rollercoaster-like fluctuations, but then the Earth entered a frigid nuclear winter, with temperatures dropping by an average of 20 degrees Celsius for over 30 years. While many of the most dangerous predators of mammals disappeared, the Earth's environment became unimaginably harsh for life.

How can mammals adapt to such harsh environments and perpetuate their species?

Continue making small animals

Before the asteroid extinction event, mammals were small in size due to intense competition and predation by dinosaurs. However, this size became an asset for the "disaster animal refugees" after the asteroid extinction.

Brusatt said, "These mammals look and behave like mice of all sizes. They usually live quietly in dark corners, but after the disaster, in this new world, the mammal population exploded because their size was perfectly suited to the terrible environment after the asteroid hit Earth."

Smaller size may help animals reproduce and increase their numbers. Ornella Bertrand, a postdoctoral researcher in mammalian paleontology at the University of Edinburgh, says that in the modern animal world, "the larger the animal, the longer its gestation period." For example, the gestation period for African elephants is 22 months, while that for mice is only about 20 days. Therefore, in the event of an apocalyptic disaster, smaller mice would have a greater chance of maintaining their population growth.

Besides long gestation periods, larger animals, especially colossal dinosaurs, take much longer to reach sexual maturity. This is another reason why dinosaurs couldn't survive the apocalyptic catastrophe. Brusatte says, "Dinosaurs took a considerable amount of time to grow to maturity. Animals like Tyrannosaurus Rex took about 20 years. This isn't to say dinosaurs didn't grow quickly, but many species were simply too enormous, requiring a long time to grow from tiny cubs to adult behemoths."

He escaped by hiding underground.

Another clue to unraveling the mystery of how mammals survived an asteroid impact is the "very strange" body shape of mammal fossils found in Paleocene and earlier strata. The ankle bones of mammals found in early Paleocene strata are small, tough, dense, and well-preserved. Shelley analyzed these ankle bones to understand how similar these mammals are to mammals living on Earth today.

She said, "We found that Paleocene mammals were very strange, unlike modern mammals. What they had in common was that they were small in size but very strong."

Small size may help accelerate animal reproduction and increase numbers.

Shelley said these mammals had strong muscles and huge bones, most similar to burrowing species that live in the ground today. "The resulting hypothesis is that animals that survived the mass extinction had a survival advantage because they were burrowing and thus able to escape the first wave of disaster after the direct impact, as well as the subsequent ground fires and nuclear winter. They could simply lie dormant underground and wait for the disaster to pass."

Let's put it this way: because these survivors of the extinction event lived, their descendants inherited this robust physique. Shelley said, "You could see this mammal 10 million years into the Paleocene, still quite clumsy even living in trees."

If the surviving mammals did indeed live underground, whether by digging their own burrows or by sharing burrows with other animals, Bertrand speculates that this might also be reflected in the agility of these mammals, or in other words, a lack of agility. She says, "We know that forests have been destroyed, so all the arboreal animals have lost their habitats. Therefore, one hypothesis is that the surviving animals are unlikely to have the same flexibility and agility as arboreal animals."

Bertrand plans to study the inner ear skeletons of mammals from this era to determine if her findings can confirm the hypothesis that these mammals survived the asteroid impact by taking refuge underground. The inner ear plays a significant role in an animal's balance; if an animal needs dexterity and agility, its skeleton will have correspondingly intricate structures. But if an animal only needs a strong physique to dig burrows, then agility is superfluous. She says, "This could give us more clues." That said, Bertrand also points out that relying too heavily on skeletons to infer animal movement behavior has its flaws, a point that left a deep impression on her after watching the recent Commonwealth Games.

Bertrand laughed and said, “I see gymnasts doing some crazy things, and I think it’s funny. We have the same bone structure, but I can’t do it. I think it’s really funny because maybe having this ability can help you survive, but you can’t tell from your bones whether you have this ability.”

Omnivorous diet provides a survival advantage

The asteroid destroyed most of the living plants on Earth, which are at the bottom of the food chain on land. Omnivorous mammals can eat almost anything and are more adaptable to the environment than animals that only eat certain specific foods, thus having a greater chance of survival.

Shelley said, "The animals that survived this mass extinction generally didn't have very specific diets." For example, Didelphodon, a close relative of a cat-sized carnivorous marsupial, only hunted one type of animal, but after the extinction, that animal became very scarce. Shelley said, "Didelphodon's diet was too limited, so it lost its way of survival. However, smaller animals can adapt their diet and lifestyle more quickly to their environment. This is a good way to survive a mass extinction."

Brusatt said that besides animals that could eat anything, a few animals with specialized diets also had an advantage, especially those that ate plant seeds. He said, "Seeds are a food bank that never runs dry. Any animal that already eats seeds can still get them during a mass extinction. So, animals like Tyrannosaurus Rex weren't so lucky; evolution didn't give them the ability to digest seeds. But for birds with beaks and some mammals that specialize in eating plant seeds, wow, isn't that a stroke of luck?"

In addition to sustaining the survival of affected animals, plant seeds also help rebuild forests and vegetation after the nuclear winter ends. "Seeds that survived the mass extinction can germinate and grow when sunlight returns," Brusat said.

Growing body but not brain

As the Paleocene epoch ended and ecosystems recovered, Earth once again flourished. Mammals began to fill the void left by the non-avian dinosaurs, becoming the most powerful life forms on Earth. Bertrand says, "After the extinction of the dinosaurs, mammals immediately began to diversify, developing in every aspect."

First, mammals' bodies grow rapidly. But the Edinburgh research team found that the size of mammalian brains has not kept pace with the rate at which their bodies have grown.

Bertrand said, "I think this is very important because we used to think that it was probably the development of intelligence that allowed mammals to survive and eventually dominate the earth. But, based on the data, it wasn't the growth of the brain that allowed animals to survive after the asteroid impact."

Mammals need to become larger and stronger to better adapt to their environment.

In fact, during the early Paleocene, a mammal's brain being too large relative to its body could be detrimental to survival. Bertrand asked, "The question is, why would you need a huge brain? Actually, an excessively large brain is quite expensive. If you have a large brain, you need to eat a lot to survive, and if you don't have enough food, you'll go extinct."

Conversely, mammals needed to become larger and stronger to adapt to their environment. In the hundreds of thousands of years following its extinction, the herbivore *Ectoconus* reached a weight of approximately 100 kilograms. *Ectoconus* belonged to the family Periptychidae, which may be related to extant ungulates. Hundreds of thousands of years is but a blink of an eye in the geological timeline. Shelley said, “It’s amazing how quickly *Ectoconus* grew to such a large size and developed herbivorous habits. You see, once there are large herbivores, there will be large carnivores, and mammals begin to evolve rapidly.”

Many other mysterious mammals also experienced rapid expansion of their bodies. Shelley said, "Animals like the Gyrodon grew very quickly and very large." A complete skeleton of the Gyrodon has not yet been found, but skull fossils have been discovered, with a skull about the size of a large buttersquito. The Gyrodon appears to be one of the species that grew robustly to adapt to burrowing after its mass extinction. Shelley said, "Its eyes were small, positioned very low, but it had huge teeth in front of them, somewhat like a rodent, but nothing more. It was a very mysterious animal."

Shelley said that these mammal species, which evolved rapidly from the survivor fauna, had long been neglected by the scientific community. She said that the scientific community had “considered them ancient, primitive, and unremarkable, but that’s not the case at all; they are truly unique. Their ancestors survived the second mass extinction in Earth’s history and were by no means slow-moving, unintelligent animals. Their survival and reproduction were incredibly diverse.”

These mammals filled the ecological void left by the extinction of the dinosaurs in many ways. While highly individualized in their lifestyles, the colossal dinosaurs were well adapted to the environment of the Late Cretaceous, but lacked the ability to survive the catastrophic world following the asteroid impact.

Brusatt said, "What's most shocking is that our Earth once had animals like dinosaurs, which survived for hundreds of millions of years and created such a great and glorious history, such as evolving themselves into behemoths the size of airplanes and carnivores the size of buses. But when the Earth suddenly underwent a drastic change, these behemoths became completely extinct in an instant. Dinosaurs could not cope with the new world and could not adapt to survival."

The asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs struck Earth faster than a bullet when it broke through the atmosphere (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech).

The randomness of asteroid impacts on Earth seems to have particularly resonated with the research team at the University of Edinburgh who study how mammals survive after mass extinctions.

Bertrand said, "We humans are here today mainly by luck. The asteroid that hit Earth could have just missed us or it could have crashed into the ocean in another part of the world. Either way, it would have led to different outcomes in the selection and evolution of future life species. Whenever I think about the randomness of this whole thing, I find it incredible."

Brusatte shared the same sentiment. He said, "An asteroid could have simply whizzed past Earth, stirred up the upper atmosphere, or even disintegrated upon approaching Earth. This asteroid had all sorts of possibilities, but it was just unlucky that it came straight at Earth."

But for mammals living on Earth today, this catastrophe may be a godsend.