I sat in Jakob Vinther's office, trying to find the right words to phrase the question I wanted to ask: Did Tyrannosaurus Rex have—the word was too embarrassing to utter—a penis? "So there had to be…" I stammered, growing increasingly flustered. "...there had to be mating," Professor Vinther replied casually.

We were at the University of Bristol in England, where Winsor is a professor of macroevolution, specializing in the fossil record. After resuming our conversation, I glanced around his room, trying to avoid eye contact. He was giving me the answers I had childlikely hoped this paleontologist would provide.

Gorgonosaurus skeleton

Professor Winsor's bookshelves were piled high with academic books and papers, interspersed with relics from a lost prehistoric world, making the entire shelf resemble layers of fossil cross-sections. Among these prehistoric fossils, the most striking was an ancient insect fossil, its delicate wing texture and mottled colors still clearly discernible. There was also the remains of a vampire squid, its black ink sac well-preserved, still containing melanin. And a strange ancient worm, a close relative of those found on coral reefs today. In the corner of the room was an antique wooden cabinet with drawers, which I expected to contain other diverse and interesting animal fossils. The room felt like an exhibition hall somewhere between a museum and a library.

Just a few feet away from me is the star exhibit of this fossil gallery, the "Psittacosaurus" (Greek for "parrot lizard"). This adorable herbivorous, small-beaked dinosaur was a close relative of Triceratops and lived in the forests of what is now Asia approximately 133 to 120 million years ago. The fossil specimen I'm seeing here is world-famous, not because it retains its complete skin, with even the striped patterns still discernible, nor because of its distinctive tail with a ring of pointed feathers. Neither of these are the reasons for its fame. Its most famous feature is that it preserves a section of its lower body that could be used by future generations to study the mysteries of its reproduction (more on that later).

Then I looked away and focused on our conversation. Winsor told me about a particularly exciting discovery at the famous Yixian Formation in Liaoning, China: two Tyrannosaurus Rex with complete feathers, nestled close together in what was once an ancient lake. When asked why it was so special, the professor said it was because the dinosaurs' posture was so strange that it raised questions about their relationship. In fact, he wondered: were these dinosaurs mating?

thorny issues

Thanks to the development of modern science and technology, scientists are now making astonishing discoveries about many subtle truths about dinosaur life at a record pace, many of which were unimaginable just a few decades ago.

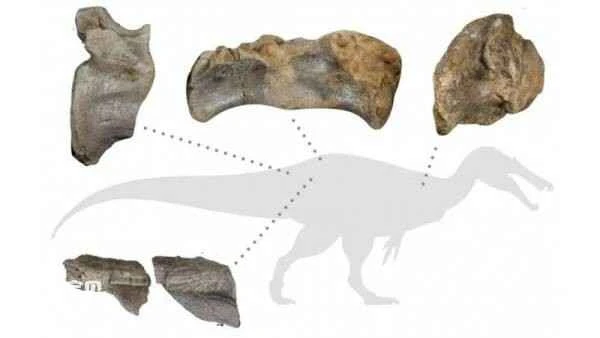

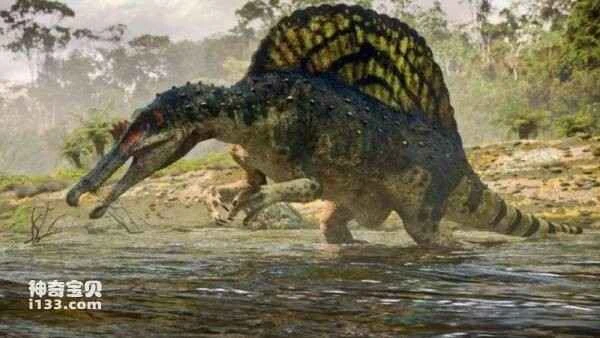

Molecular biology research has confirmed that theropod dinosaurs from 76 million years ago possessed red blood cells and collagen. Among these dinosaurs was Tyrannosaurus Rex, once the largest carnivore on Earth. The indicative chemical signatures discovered in this study suggest that Triceratops and Stegosaurus were rare cold-blooded dinosaurs, while another herbivorous dinosaur with spikes and heavy armor had an orange-red coat. Scientists have also discovered that Spinosaurus, known for its "giant sail" on its back, likely used its 15-centimeter teeth and crocodile-like jaws to hunt in deep water. There is also evidence that Iguanodon may have been remarkably intelligent, while flying pterosaurs (though not strictly dinosaurs, but actually winged reptiles) often hunted on foot.

However, how dinosaurs mated, or any research on dinosaur reproduction, remains completely blank. Even today, scientists cannot accurately distinguish whether dinosaur fossils are male or female, let alone know how dinosaurs courted and mated, or what kind of reproductive organs they had. Without this basic knowledge, most of the physiological phenomena and behaviors of dinosaurs will remain shrouded in mystery. But one thing is certain: dinosaurs definitely mated.

Studying dinosaur fossils can help us understand the lives of dinosaurs.

Returning to the topic of the Tyrannosaurus Rex fossils, Winsser explained that another ancient lake site, the Messel Pit in Germany, could provide a clue to unraveling the mystery of the dinosaurs' unusual posture. Originally a quarry, the Messel Pit became famous for its vast collection of well-preserved animal and plant fossils and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The remains of these fossils appear as if they were squeezed into a book. Researchers have discovered fossils such as a fox-sized horse, giant ants, early primates, and several animals with bloated stomachs, including a snake with a lizard in its stomach, and a beetle in the lizard's stomach. Numerous freshwater turtles have also been found, at least nine pairs of which died suddenly during mating. Several pairs still show their tails in the contact position during mating. The mating patterns of the freshwater turtles at the Messel Pit offer significant insights into Winsser's theory of dinosaur mating.

The Messel Crater's status as a prehistoric cemetery for a vast number of ancient animals stems from a toxic secret. During the Eocene epoch, between 57 and 36 million years ago, the Messel Crater was likely a steep, water-filled volcanic crater surrounded by dense subtropical forests. No scientific conclusion has definitively stated how this volcanic lake caused the sudden death of so many plants and animals. One hypothesis suggests that active geological activity continued after the lake's formation, periodically releasing suffocating carbon dioxide fumes. These unfortunate turtles may have been trapped and perished during one such release, sinking to the lakebed where their mating postures were preserved for tens of millions of years in the oxygen-deprived silt.

However, these freshwater turtles, who died while "passionate," did not mate in the same way as they usually do, with one riding on the other's back. Instead, they were back to back, as if the two turtles had suddenly changed their minds and wanted to turn away from each other.

Professor Winsell sensed my confusion and leaned back in his chair, explaining that the bodies of mating freshwater turtles should gradually separate after death, but because their genitals remain connected, they remain joined together. Winsell's expression and tone suggested that he considered discussing prehistoric animal sexual behavior a perfectly normal topic.

Returning to the freshwater turtles mating in the Messel Pit, the unusual pose of these two Tyrannosaurus Rex fossils is striking because of some uncanny similarities between the two pairs. Wensell says the pair of T. Rex were "separated from each other, but their tails were overlapping. I think the T. Rex suddenly met with a terrible accident while mating."

Aside from this, there is no other case evidence, and Winsser admits that his theory is based on highly hypothetical scenarios and remains an unpublished idea. Many fossils of soft organs from dinosaurs have yet to be discovered, and if this pair of Tyrannosaurus Rex were indeed trapped in ancient mating, this phenomenon would reveal some information about the soft organs of certain dinosaurs. That is to say, Tyrannosaurus Rex, and possibly Tyrannosaurus Rexes, may have had penises.

Submerged at the bottom of the lake

However, there is another, more definitive source of information about the truth of dinosaur sex: a fossil that has captured the world's attention with its lower body. This is the aforementioned Psittacosaurus.

No one knows what position the largest dinosaurs used for mating. Some speculate that the male lay on top of the female during mating, but it's unclear how they could avoid crushing their mate in such a position.

Winsser showed me this treasure from his collection and explained its history to me.

This is an ancient ecosystem in Northeast China, the Jehol Biota of the Early Cretaceous. Let's imagine it's a sunny day in this temperate land, and the little Psittacosaurus decides to leave its densely forested home to drink from one of the region's many lakes. Measuring about 91 centimeters from head to tail, reminiscent of an unusually robust Labrador Retriever, it was almost an adult but had not yet experienced sexual intercourse.

This psittacosaurus walked to the lake on two legs, as it no longer walks on all fours after reaching adulthood, but tragedy struck. Just as it bent down to drink some water with its parrot-like beak, it slipped and fell into the lake, drowning. As it fell to the bottom of the lake, lying on its back in an unseemly position, it miraculously preserved its genitals, which may now be of interest to future humans.

Of course, Winsor was particularly eager to show me this famous genitalia. He pointed to a black, circular patch of skin beneath the Psittacosaurus's tail—its genitals, remarkably well-preserved since the Early Cretaceous period. That era is so distant, spanning a time span equivalent to 1.6 million times the average human lifespan today.

Alas, the Psittacosaurus in Winsor's office isn't a real fossil; what I see now is a model he commissioned made to scale. But the model is perfect, meticulously crafted, replicating the precise stripes found on the original fossil's skin as accurately as possible, even down to the markings.

So, what information can we get from the genitals of this little dinosaur?

First, like its close relatives such as birds and crocodiles, this dinosaur also had a cloaca. This multi-purpose excretory opening is common in all terrestrial vertebrates, except for mammals. It is a separate passage used for defecation, urination, sexual intercourse, and reproduction. This is not unexpected, but it is a new discovery, as no one had previously confirmed that dinosaurs shared the same reproductive structure as their evolutionary cousins.

Professor Wensell said, "So you can see, look down here (he pointed to the cloaca under the Psittacosaurus's tail) there's a lot of pigment." He explained that this is melanin, which may have played a role in the fossil's excellent preservation.

Our understanding of dinosaurs still requires further research.

While we generally only know melanin as the dark compound that gives our skin its color, it actually has countless uses in the natural world, from squid ink to the protective layer behind our eyes. Melanin is also an effective antibacterial agent; high concentrations are typically found in the livers of amphibians and reptiles, where it inhibits the growth of potentially harmful microorganisms. Crucially, melanin has also been found to play a protective role in many other living environments.

“For example, insects…use melanin as a kind of immune system to protect themselves from infection. So if you poke a hole in a moth with a needle (which I don’t recommend), then melanin will be secreted around the hole you poke,” Professor Winsor said.

Because of the immune function of melanin, many animals, including humans, have a higher concentration of melanin around their genitals, resulting in a darker skin color in that area. This was true for dinosaurs, and it was true for humans as well. Looking at this distant human relative before me, as one of my colleagues pointed out, I felt as if it were frozen in this pose forever as it tiptoed past me. It felt strange to discover how close dinosaurs were to us.

But there were many more interesting discoveries to come. Clearly, all my strangeness so far was just a warm-up; there was much more to come. Before I even knew it, Winsor began enthusiastically explaining to me in detail many other features of the Psittacosaurus's lower body.

Professor Winsell said, “Now we can reconstruct what the cloaca of Psittacosaurus looked like, and we can show that it had two lips that opened like this.” As he said this, Winsell spread his fingers and made a V-shape. “There is melanin outside the opening. But here’s the interesting thing: the melanin is not at the opening (if it were to prevent microbial infection, then the melanin should be at the opening), so the melanin is on the outside for publicity and showing off.”

If this were true, like baboons flaunting their hindquarters to mates, it would be unprecedented, as such courtship behavior is extremely rare even among the descendants of avian dinosaurs—modern birds. Winsser says dinosaurs "used a lot of visual cues," explaining that their color perception was exceptional; unlike most mammals that can only see two colors, birds could see not only the three colors humans can distinguish, but also ultraviolet light. "But it makes no sense for birds to display their cloaca, because it's covered in feathers." Similarly, crocodiles rely more on scent to attract mates.

Some experts believe that Spinosaurus used the sail-like structure on its back as an aid in swimming, but it is also possible that it was used for courtship.

Winsser speculates that, like birds, dinosaurs may have had excellent color vision, and in this case, featherless dinosaurs might have seized the opportunity, thinking, "Why not show off your cloaca?"

Unfortunately, we cannot determine whether this Psittacosaurus was male or female, nor can we determine what kind of sex organs it possessed, as their respective sex organs are located within the cloaca. This leads to two possible mating strategies. One is the so-called "cloacal kiss," where the two dinosaurs lay on top of each other, and the male ejaculated directly into the female's cloaca through its cloaca—a common mating strategy in birds. The other is the more familiar version, which involves penile mating, as is the case with crocodiles.

Since there is no further evidence and no other dinosaur cloaca fossils to study, the above view remains inconclusive.

We've probably talked enough about dinosaur genitalia. But what about other aspects of dinosaur mating and reproduction? Did they have courtship rituals? For example, fights between members of the same sex for mates, or even elaborate dances? Did males and females look different? And how can we tell which features dinosaurs used to attract mates?

Attracting the opposite sex

At first glance, deciphering the mating behavior of long-extinct animals seems like an impossible task, much like searching for fossils of their genitals. But Rob Knell, an evolutionary ecologist at Queen Mary, University of London, assures me that there are clues hidden in the fossil record that has been collected.

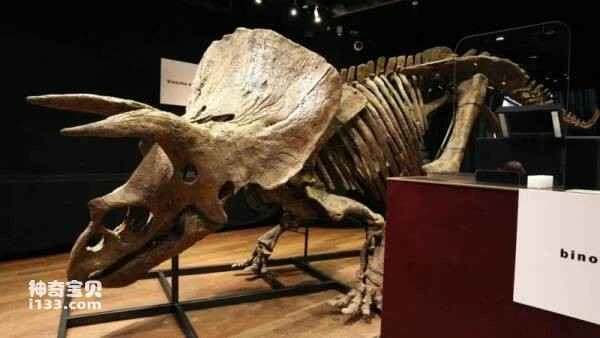

Nair told me, “One of the things we study about dinosaurs is that they have a lot of strange things about them, which some people call ‘weird structures.’ And that’s part of what makes dinosaurs so fascinating. So the discs on Stegosaurus, the large sails on Spinosaurus’s back, the folds and horns on Triceratops and other ceratopsians, and the large crest on Hadrosaurus can all be seen as good examples of sexual selection traits.”

For 200 years, scientists have debated the function of these bizarre structures on dinosaurs, often resorting to outlandish theories. For example, some have suggested that hadrosaurs, being aquatic animals, used their crests as ventilation tubes or air chambers. Sometimes, the strange shapes of dinosaurs are hard to believe; for instance, when Tyrannosaurus Rex fossils were first discovered in 1900, their forelimbs were so small compared to their massive bodies that it was initially doubted they belonged to the dinosaur itself. Some skeletons were even initially thought to belong to another dinosaur.

Deciphering the mating behavior of long-extinct animals seems like an impossible task, much like searching for fossilized genitalia.

However, Nair explained that in the past, paleontologists were reluctant to interpret these bizarre shapes as tools for attracting mates or competing with each other. They could speculate that this might have been the dinosaur's ultimate goal, but not proving this hypothesis seemed like an unscientific approach.

"The disc-shaped thing on the back of a Stegosaurus is one example. Or the tubular crest on a duckbill head could also be an example... We don't know what they were used for," said Susannah Maidment, a senior paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London.

Then came the era of contemporary scientific research. As early as 2012, Nair had decided to study this issue more seriously. He was particularly interested in studying strange features that were very similar to the mating behaviors of animals in the modern world, or features that could not be explained by other theories. For example, the horns and folds on the heads of Triceratops and its close relative Psittacosaurus (Psittacosaurus had unusual lateral spikes on its cheeks), the crest on the head of the predatory dinosaur Dilophosaurus with a prominent ridge above each eye, as well as the giant-like long necks of Diplodocus, and the feathers of the dinosaur ancestors of birds.

Although there is no clear method to determine what these strange body structures are for, Nair and an international team of scientists quickly realized that compelling clues could be found in animals still alive today, provided you know where to look.

One approach is to look for sexual dimorphism, which refers to the significant differences in appearance between males and females of a species. Animals rarely have completely different lifestyles and survival strategies, so differences in physical characteristics usually serve to allow males to directly attract females (e.g., the colorful plumage of a male peacock) or to compete with other males for mating rights (e.g., the antlers of a male deer).

Unfortunately, this particular clue is not very helpful in understanding the sexual life of dinosaurs, because scientists cannot yet distinguish between males and females. Even if differences are found between individual fossils, it is impossible to determine whether they are dinosaurs of different sexes or different branches of the same species.

This leads to the next clue. If a feature appears only in adult dinosaurs and not in infants or young children, it is usually for sexual reproduction, just as a lion's mane is considered a sign that the male lion is ready to mate. However, getting started with this research is also tricky.

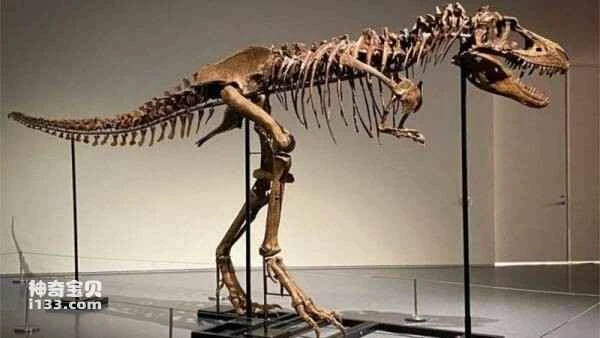

Back in 1942, scientists unearthed a stunning new skull fossil of a dinosaur in Montana, USA. It clearly belonged to a fearsome predatory dinosaur, but was relatively small and slender compared to the ultimate predator, Tyrannosaurus Rex. The research team concluded that it was an adult dinosaur of a new species, and after decades of debate, the discovery was finally named *Dwarf Tyrannosaurus*. In the following years, several more skeletons that might be those of this so-called *Dwarf Tyrannosaurus* were discovered.

Then in 2020, a scientific team conducted a more detailed study. They analyzed the skeletons of two possible pygmy tyrannosaurus rex and realized that these might not be a separate species from Tyrannosaurus rex at all; they were indeed Tyrannosaurus rex, but those that had died in their juvenile stage before reaching full maturity. In fact, the misunderstanding arose because these smaller, juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex looked very different from the adult ones, almost appearing as if they were truly unrelated species, each occupying a unique position in the prehistoric food chain.

Tyrannosaurus Rex was not the only dinosaur to evolve significant developmental changes.

"There's a lot of debate about Triceratops and Hornedosaurus," Medment said. "While the two dinosaurs look very similar, the former had a massive skull, one of the largest among land animals, and a huge ring-shaped collar around its neck with a large hole in it. The latter was much smaller, and its smaller collar lacked the hole."

The fossils in Messel Crater were formed millions of years after the extinction of the dinosaurs, but they still reveal information about how prehistoric animals mated.

"These are two dinosaurs that lived in the same era and region, both in North America during the Late Cretaceous," Medment said. "Some people think that Triceratops is a later-stage Triceratops, while others think they are two different species." She also cited other examples that some people believe are simply variations of Triceratops at different life stages. "Some people argue that these are different species, but in reality, they could just be Triceratops at different stages of ontogeny. However, no one really agrees."

Therefore, this strategy of identifying features is not necessarily effective. But fortunately, there is another approach: modeling other aspects of this body structure that may be useful.

Nair said, "That's all we can do, okay, (the modeling results show) this is consistent with structures that evolved for this purpose (mating), but not with structures that evolved for any other purpose."

The massive folds of Triceratops are one example. For years, generations of scientists have been puzzled by this enormous physical feature of Triceratops, with various speculations, such as protecting its neck from predators, regulating body temperature, or even simply providing muscle connections so that Triceratops could swing its horns more powerfully.

Recently, it was suggested that neck folds could have helped Triceratops identify members of their group. Therefore, Neil and his colleagues conducted further research and found this idea unfeasible because the folds showed almost no variation across different Triceratops species, making it unlikely that this was the purpose of their evolution. Since this theory may not hold true, we can more reasonably speculate that their true purpose was to impress other Triceratops or deter other males to secure mating opportunities.

The evidence has emerged. In a 2009 study, researchers analyzed injury patterns on the skulls of several Triceratops and found that they were consistent with wounds left from fights with other Triceratops. Researchers may have uncovered the lingering effects of ancient animal mating competition.

Were there other courtship rituals? Did male Tyrannosaurus Rex really wriggle their small forelimbs to attract females, as the producers of the TV series *Prehistoric Planet* recently suggested? Could Pachycephalosaurus have used headbutting to win in the battle for mating? To please the opposite sex, did male Velociraptors build elaborate pergolas, perhaps even choosing only the bluest berries to decorate their masterpieces?

The large folds on the neck of Triceratops have long been considered a protective tool against predators, but could they actually have served a courtship function?

Nair believes that, more broadly, there should be other courtship and mating rituals. He points out that there are many similarities between dinosaurs and birds; in fact, today's birds are descendants of their ancient feathered dinosaur cousins, only with beaks and no teeth. Therefore, avian dinosaurs are even more similar to today's birds; for example, Velociraptors are more like ferocious turkeys than the sleek carnivores depicted in the Jurassic Park movies.

Nair said, "If you observe birds today, you'll find that they exhibit a wide range of courtship methods. So why couldn't dinosaurs do the same? There's no reason to believe that some of the strange mating traits of dinosaurs weren't passed down to birds... Therefore, I think dinosaurs had some bizarre mating methods."

Surprisingly, they might even find physical evidence of bizarre courtship behaviors in dinosaurs. In 2016, scientists discovered some unusual bedrock formations while excavating in Colorado, which almost resembled ancient waterholes.

However, closer inspection revealed clear scratches and three-toed footprints on the rock bed, the tracks left by predators such as Tyrannosaurus Rex during the Cretaceous period. These tracks were not accidental undulations on the land surface, but were made by dinosaurs, and look like enlarged versions of the tracks left by ostriches today.

Female ostriches are notoriously difficult to please, so male ostriches must perform elaborate courtship dances to win their affections. This complex courtship ritual includes a high-speed sprint with vigorous wing flapping and a "scratching ceremony" to demonstrate their digging skills, essential for nest building on the ground. Researchers believe that scratches left on the Colorado bedrock suggest that Tyrannosaurus Rex may have performed similar courtship behaviors 100 million years ago.

However, Nair believes we may never know the bizarre details of most dinosaur mating rituals. Even among extant dinosaur relatives, such as various birds of paradise, their mating rituals varied greatly. He said, "Even if you wanted to predict, you wouldn't get very far."

However, in recent years, humans have gained much insight into the lives of dinosaurs that was previously unimaginable. Who knows, perhaps decades from now, with advancements in technology and the growth of knowledge, the bizarre and unusual courtship methods of dinosaurs will be deciphered one by one, and the sheer amount of information available will be unsettling. Yes, we will also know what dinosaur genitals actually looked like then.