The Tibetan antelope, scientifically known as *Odontodon spp.*, is the only species in the genus *Odontodon* within the subfamily Antelopeinae of the family Bovidae in the order Artiodactyla. The earliest scientific description of the Tibetan antelope was made by the British naturalist Clarke Abel in 1826, but he died in November of the same year before he could name it. It was later named by the British naturalist Brian Houghton Hodgson in 1834.

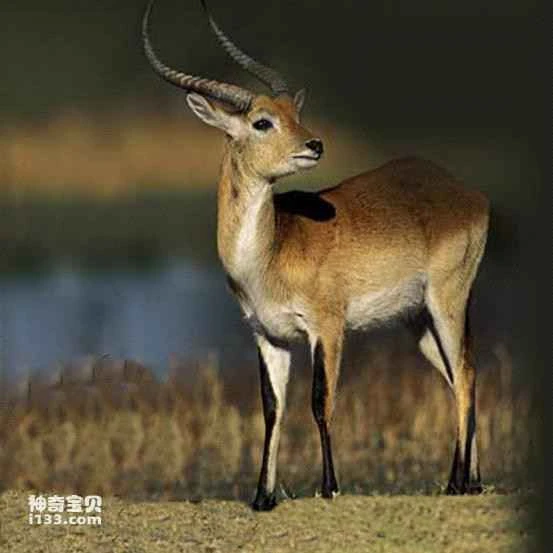

The Tibetan antelope has a reddish-brown back and a light brown or grayish-white belly. Adult male Tibetan antelopes have black faces, black markings on their legs, and harp-shaped horns for defense. Female Tibetan antelopes do not have horns. The underfur of the Tibetan antelope is very soft. Adult female Tibetan antelopes are about 75 cm tall and weigh about 25-30 kg. Males are about 80-85 cm tall and weigh about 35-40 kg. Tibetan antelopes reach sexual maturity at 2 years old. Males generally do not live past 8 years, and females generally do not live past 12 years, although they can live up to nearly 10 years in captivity. Tibetan antelopes inhabit altitudes of 3250-5500 meters, but are best adapted to flat terrain at around 4000 meters.

Tibetan antelopes primarily inhabit alpine meadows, alpine meadow steppes, alpine desert steppes, and alpine deserts at altitudes of 4,000-5,000 meters, all sparsely populated areas. Vegetation there is sparse, consisting mainly of needlegrass, moss, and lichens, which are their main food source. In the wild, wolves, brown bears, lynxes, snow leopards, golden eagles, and Himalayan vultures are their main predators. In the harsh environment of the plateau, to find sufficient food and withstand the extreme cold, Tibetan antelopes have, through long-term adaptation, developed a herd migration habit and possess a layer of highly insulating downy fur. Along with wild yaks and Tibetan wild asses, Tibetan antelopes are known as the "three major families" of the northern Tibetan Plateau and are a flagship species of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.

The Tibetan antelope is endemic to China. According to the research of German-American wildlife biologist George Schaller, it can be roughly divided into several non-migratory populations and four major migratory populations. It mainly inhabits the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the Altun Mountains of Xinjiang, with its distribution area roughly centered on the northern Tibetan Plateau (Qiangtang), extending south to north of Lhasa, north to the Kunlun Mountains, east to northern Changdu Prefecture in Tibet and southwestern Qinghai, and west to the Sino-Indian border. Occasionally, a small number migrate into Ladakh, Indian-administered Kashmir. Tibetan antelopes were still found in Nepal until the first half of the 19th century, after which they became extinct. The Tibetan antelope was listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in 1975, and further added to Appendix I in 1979, prohibiting trade in this species. The 1988 National Key Protected Wild Animals List established it as a Class I protected wild animal in China. The Tibetan antelope is widely recognized as a typical representative of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau fauna and an important indicator species of its natural ecosystem.

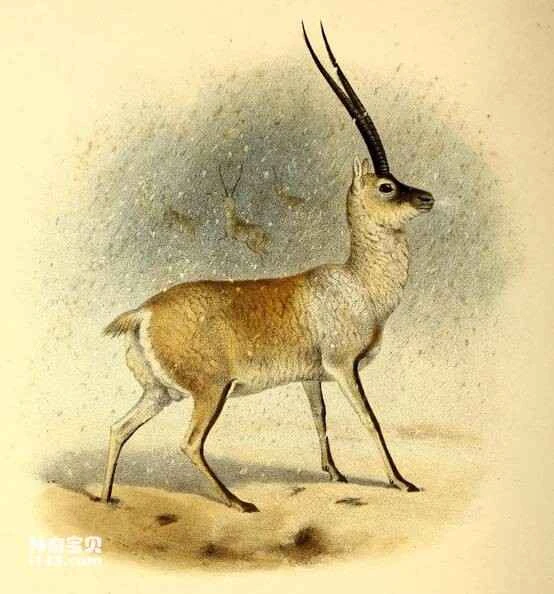

The Tibetan antelope is a very ancient species. Its ancestors can be traced back to the Querliqnoria, which was distributed in the Qaidam Basin during the Late Miocene (about 25 million years ago). Fossils of this animal have straight, upward-pointing horns similar to those of the Tibetan antelope. Fossils of Pantholops hundesiensis, a Pleistocene extinct species in the same genus as the Tibetan antelope, were found at high altitudes in the Niti Pass on the Sino-Indian border.[3] The “Lingyang” recorded in the ancient Chinese mythology Classic of Mountains and Seas is very similar in appearance to the Tibetan antelope. Modern Tibetan antelopes are much larger than their ancestors from millions of years ago. Ten million years ago, the Himalayas experienced a strong orogenic movement, and the forests in northern Tibet disappeared. Various animals either scattered and fled or evolved rapidly, but the native species Tibetan antelope, wild yak, and Tibetan wild ass have remained here. Around 10,000 years ago, the altitude of northern Tibet rose again, and the climate became even colder and drier. Over a long period of evolution, the Tibetan antelope developed adaptations in both morphology and physical characteristics to this high-altitude, low-oxygen environment. Today, located in the subtropical latitudes of the northern Tibetan Plateau, with its high altitude, abundant sunshine, and thin air, the Tibetan antelope has become the dominant species. To breathe more oxygen, the Tibetan antelope has developed a wide mouth and enlarged nasal cavity with bulging sides to increase air contact area. The quality of Tibetan antelope wool is recognized worldwide, which is also the main reason for their poaching. These hollow, densely packed wool layers cover their bodies, providing insulation in sunlight and protection from wind and cold during blizzards. From June to October each year, they undergo a long molting season, creating a comfortable temperature year-round, much like having a built-in blanket-like air conditioner. To evade predators such as wolves, lynxes, and snow leopards, Tibetan antelopes can run at an average speed of 80 kilometers per hour. Especially for calves, whose bones calcify just three days after birth, they can run faster than wolves. Furthermore, Tibetan antelopes are accustomed to living in herds, often moving in groups of several thousand during seasonal migrations, which also reduces the risk of predation.

The origin of the Tibetan antelope provides another interesting example of a species endemic to the Tibetan Plateau, with its ancestors traceable back to the Late Miocene. In the Qaidam Basin of northern Tibet, the extinct bovid (Qurliqnoria), with its upright horns, has long been considered an ancestor of the Tibetan antelope. A fragmented horn core of the Qurliqnoria has also been found in Early Miocene strata of the Zanda Basin. Importantly, mammals in the Late Miocene of the Qaidam Basin began to show a degree of localization. Some notable bovids, such as *Tsaidamotherium*, *Olonbulukia*, Qurliqnoria, *Tossunnoria*, and a pronghorn deer, were almost exclusively found in the Qaidam region. A Pleistocene extinct species of Tibetan antelope, *Pantholops hundesiensis*, was found at high altitudes near the Niti Pass on the Sino-Indian border. Assuming that the Qurliqnoria is closely related to the Tibetan antelope as indicated by its horn core morphology, the Tibetan antelope's origin on the Tibetan Plateau is quite plausible.