Radiolarians are single-celled protozoa that float in the ocean, named for their radially arranged filamentous pseudopodia.

Protozoa are the most primitive group of animals, each consisting of only a single cell. Scientists classify them into a single phylum, Protozoa. However, this single cell of a protozoan is a complete organism, possessing the essential life functions of an animal. The various parts of the cell differentiate, each controlling a specific function, forming "organoids." Protozoa often possess flagella, cilia, or pseudopodia as their organs of locomotion. Some protozoa have a skeletal structure in their cytoplasm or form a robust exoskeleton.

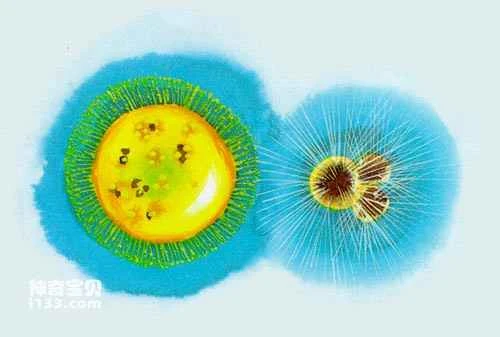

radiolaria

Protozoa are extremely small, generally less than 250 micrometers in size, which means they are less than a quarter the size of a 1-millimeter-long grain of rice. Such tiny bodies can only be observed under a microscope.

However, these inconspicuous little animals are widely distributed, mostly living in oceans or freshwater areas, while some live in damp soil or lead parasitic lives.

Scientists have classified these animals into four classes based on whether they have locomotor organs or what type of locomotor organs they have: flagellates, ciliates, sporozoites, and sarcoptera.

Radiolarians belong to the class Sarcopoda. Their main difference from other protozoa is the presence of a chitinous central sac in their cytoplasm, dividing the cytoplasm into an extra-sac portion and an intra-sac portion. The sac is covered by a cuticle membrane with pores, allowing communication between the intra-sac and extra-sac cytoplasm.

Radiolarians come in various shapes, including spherical and bell-shaped, with body diameters ranging from 100 to 2500 micrometers. Their cytoplasmic skeletons are typically enclosed within the cells, and their chemical composition varies among species, mostly being siliceous or containing organic matter, with a few containing strontium carbonate. Radiolarian skeletons fall into three types: a loose structure composed of unconnected or loosely joined rods, spicules, and spines; a tennis ball structure, where the skeleton is spherical, spindle-shaped, or conical, tightly connected along the central cyst membrane to form a network; and a concentric structure, composed of multiple concentrically arranged grids, with numerous needles, hooks, and columnar segments connecting the layers to create an intricate and beautiful shell shape. Based on these different skeletal structures, and to some extent considering the structural characteristics of the central cyst, scientists have classified radiolarians into three suborders: Echinochloae, Polycystiformes, and Brown Cysticeridae. The Polycystiformes are further divided into two main categories: foamy worms and cage worms.

Radiolarians are pelagic organisms that prefer oceanic environments and are geographically widespread, found in almost all the world's oceans. Most radiolarians inhabit warm waters, with those near the equator being particularly abundant and diverse; up to 40,000 radiolarians can live in a typical bathtub-sized volume of seawater (about half a cubic meter)! In the waters near the North and South Poles, radiolarians also thrive alongside diatoms. Scientists have categorized modern ocean radiolarians into typical surface combinations based on their distribution: polar, near-polar, subtropical, and tropical zones. Due to variations in physicochemical conditions at different depths below the surface, radiolarians exhibit different combinations at different depths. Echinochloaminformes and foam worms are typically confined to the photic zone, while scaly worms and brown cystidia live at depths exceeding 2000 meters below the surface.

After radiolarians die, their siliceous shells sink to the seabed and do not easily dissolve, thus accumulating in large quantities. The density of these deposits is astonishing; a single sediment the size of a matchbox (about 2 cubic centimeters) can contain more than 120,000 individuals. These radiolarian shells accumulated on the seabed form the famous radiolarian slime, which covers 3.4% of the Earth's ocean floor.

Radiolarians have a very long history, but because the skeletons of the suborders Echinochloa and Chrysosphaeria are weakly fused and easily damaged, they are difficult to preserve as fossils. Therefore, most radiolarian fossils commonly found in strata belong to the suborder Polycystia. They appeared in the Cambrian and flourished in the Late Devonian and Carboniferous periods. Radiolarian fossils are abundant in France, Britain, the Ural region of Russia, North America, and Australia. During the Paleozoic era, spirozoans were the most common, for example, the radiolarian rocks found in the Early Permian strata of Renhua area, Qujiang County, Guangdong Province, my country, are mostly composed of spirozoans.

By the Mesozoic Era, both groups of polycystidia had been found. Radiolarian fossils from the Triassic period are relatively rare, but both spiropods and scaly larvae have been discovered in siliceous rocks of the Late Triassic strata near Mount Everest in my country. During the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, radiolarians evolved to a new level, with shell shapes becoming more complex and many new types appearing, distributed in the Tethys Sea and the Pacific Ocean.

The Cenozoic Era was the climax of radiolarian development, especially during the Eocene and Miocene, when all groups of radiolarians appeared and spread widely throughout the world, forming many representative fossil assemblages. Some scientists have used radiolarian fossils to classify Tertiary strata.