We already know that the oldest known groups of hominids were mostly found in eastern Africa. But the story doesn't end there.

Early human footprints

In 1976, a research team led by Mary Leakey discovered footprints in volcanic ash deposits in the Letori region dating back approximately 4 million years, which appeared to be those of bipedal hominids. The footprints included those of adults as well as relatively short and wide footprints of children.

On September 22, 1994, Tim White and other anthropologists published an article in the prestigious British journal *Nature*, announcing the discovery of even earlier hominid fossils in the Alpha region, dating back 4.4 million years. These were the earliest hominid fossils discovered to date, considered representative of the earliest humans to have moved from the trees in forests to the open ground of the savanna, and were therefore named *Archaeopteryx*.

Because the earliest hominids discovered to date all originated in East Africa, most anthropologists now believe that the earliest humans originated in Africa.

So why have the earliest human fossils been found in East Africa? What happened in Africa at that time?

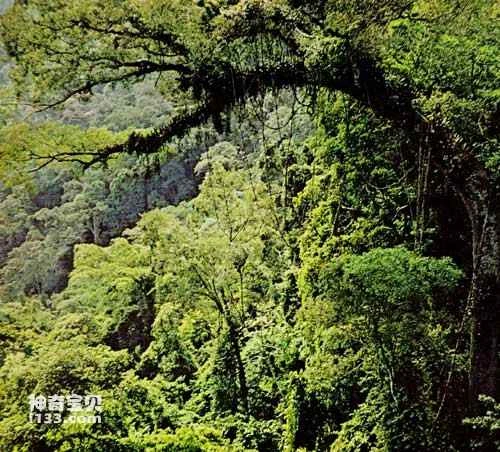

Geological and paleontological studies tell us that 15 million years ago, the entire continent of Africa was covered by a vast tropical rainforest from west to east; it was a paradise for primates, inhabited by all kinds of monkeys (members of the superfamily Macea) and apes (members of the family Phyllostachyidae within the superfamily Anthropoidea), and unlike today, there were far more ape species than monkey species at that time.

tropical rainforest

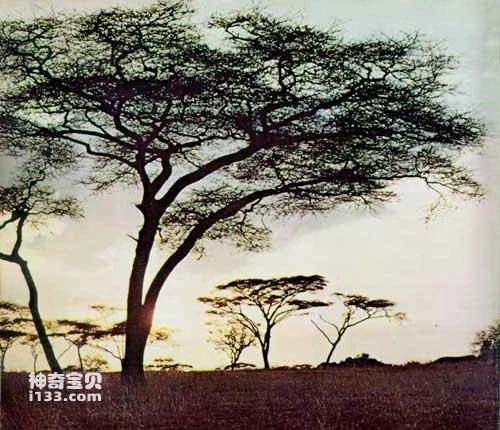

Later, geological movements altered the environment. The Earth's crust in eastern Africa cracked along a line connecting the Red Sea, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania, causing lava from deep within the crust to intermittently erupt to the surface. This lava erupting, cooling, erupting again, cooling again… resulted in the gradual rise of the landmass in Ethiopia and Kenya, forming a broad plateau over 270 meters above sea level. The formation of this broad plateau not only changed Africa's topography but also its climate. It obstructed the previously uniform, moisture-rich airflow from west to east, resulting in the eastern part of the plateau becoming arid and lacking rainfall, thus losing the conditions for tropical rainforest growth. From then on, the continuous African rainforest began to break apart in the east, interspersed with savanna and shrubland.

savanna

Changes in the environment inevitably subject many existing variations in biological populations to the test of natural selection; this mosaic ecological environment provides opportunities for the survival of multiple variation types; however, once a suitable environment disappears, the variation types adapted to this particular environment will face extinction; when many such intermediate variation types disappear, some of the variation types that remain are likely to be very different from the original types, at which point they have become new species, that is, the biological types have been renewed and the organisms have evolved.

This is exactly what happened in East Africa around the time of human origins. As early as the 1960s, the Dutch paleoanthropologist Kottrant recognized this; after a period of neglect, in 1994, the French anthropologist Yves Copinus re-examined this process, which is now recognized by most scientists as the so-called "Eastern story of human origins."

The beginning of the story has already been explained; the following scenario is as follows.

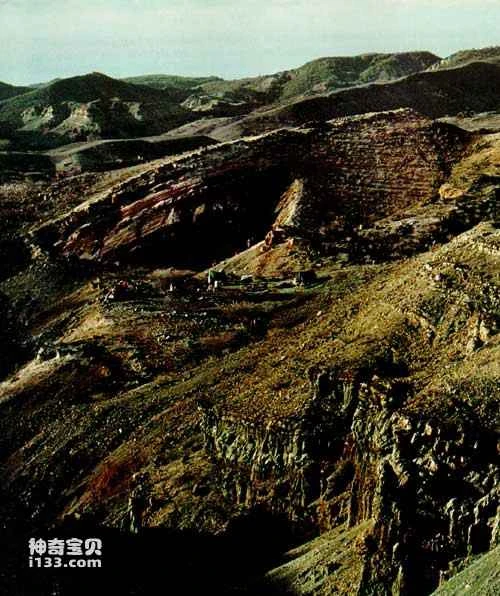

East African Rift Valley

Around 12 million years ago, continuous geological tectonic forces further altered East Africa. Along the line where the Earth's crust initially split, a long, winding rift valley, known as the East African Rift Valley, formed from south to north. The East African Rift Valley begins in Mozambique, extends north through Tanzania, and branches into two branches: the eastern branch extends northeast, through Ethiopia, to the Red Sea; the western branch extends northwest, through Uganda, into Sudan. The formation of the rift valley produced two biological effects: firstly, it created an insurmountable barrier hindering the east-west movement of fauna; secondly, it further promoted the development of a mosaic ecosystem.

It was precisely because of this environmental force that the population of the common ancestor of humans and modern African apes naturally separated. The descendants of these common ancestors who remained in West Africa continued to slowly evolve along the path of adapting to life in the tropical rainforest, eventually forming modern gorillas and chimpanzees; conversely, one branch of the descendants of these common ancestors who remained in East Africa, under the selective pressure of a new life on open ground, developed a completely new set of skills, namely bipedal walking and the series of adaptations that followed, which is humankind; while at the same time, most of the African apes that had flourished 15 million years ago became extinct due to environmental changes.

Bipedalism is of particular importance to the origin and evolution of humankind. The common ancestor of humans and African great apes lived in the ancient African rainforest and was therefore adapted to vertical movement, climbing up and down tree branches. They occasionally descended to the ground, but unlike modern chimpanzees, they did not walk on their knuckles. After the formation of the Great Rift Valley, the climate of East Africa became arid, and the rainforest was replaced by vast mosaic tropical savannas. Our ancestors did not immediately adapt to all these changes; they still needed to forage and sleep in the forest, and their food still largely depended on the forest (e.g., fruit from trees). However, the tropical savanna environment no longer allowed them to climb up and down the trees as they had in the past; they needed to frequently move from one thicket to another. This movement inevitably involved crossing the ground, which increased the demands on efficient ground movement. Since our ancestors had long adapted to vertical locomotion by climbing up and down trees, the irreversibility of evolution determined that they could not walk and run on four legs like cats, dogs, cows, and sheep after coming down to the ground. At this point, bipedal walking became the most efficient way of locomotion, and its superiority was obviously far greater than the knuckle walking method of chimpanzees.

It's easy to imagine that when our ancestors first came to the ground, their steps were clumsy and unsteady. The skill of bipedal walking developed gradually. From fossil discoveries, we know that while Australopithecus and Arborea hadn't reached the level of sophistication that we humans are today, they were already capable of relatively good bipedal walking.