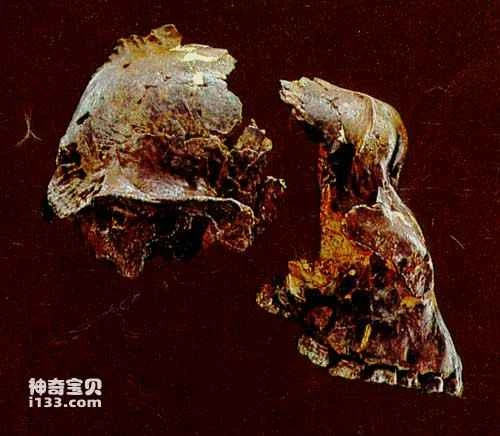

While Dart and Bloom continued their discoveries of Australopithecus in South Africa, the renowned British paleoanthropologists, Louis and Mary Leakey, were also making tireless efforts in East Africa. On July 17, 1959, after nearly 30 years of relentless searching, they finally received their reward: Mary discovered a nearly complete skull and a shinbone of Australopithecus in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. The skull was particularly robust, with molars similar to those of the robust Australopithecus species in South Africa, but even more robust than its South African cousin. Louis named the specimen *Australopithecus africanus* Bois, in gratitude for the support Mr. Charles Boyce had provided to their work in Olduvai Gorge and other areas. The name *Australopithecus africanus* has now been abandoned, and the corresponding specimen is now called *Australopithecus africanus* Bois, dating back to approximately 1.75 million years ago.

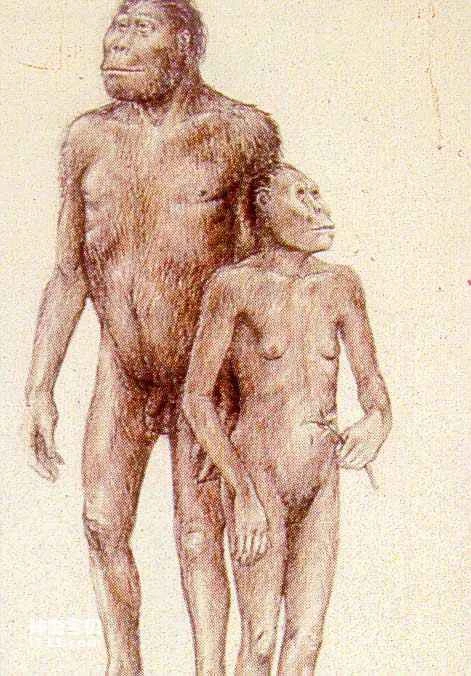

Sexual dimorphism in Australopithecus boise

Starting in 1967, anthropologist Howell from the University of California, Berkeley, led an excavation team to investigate and excavate in the Omo Valley of Ethiopia, where they discovered a large number of hominid fossils. Among them, those dating back about 3 million years are similar to Australopithecus africanus, while those dating back about 2 million years are similar to Australopithecus bosbaceus.

Beginning in 1968, Richard Leakey, the Leakeys' son, led a team on a large-scale excavation east of Lake Tekana in Kenya, obtaining many well-preserved and remarkably complete skulls, some of which closely resembled those of *Australopithecus boisei* discovered in Olduvai, Tanzania. The size of these bones revealed that male *Australopithecus* were significantly larger than females: it is estimated that males could exceed 1.5 meters in height, while females were almost less than 1.22 meters; males also weighed nearly twice as much as females! This dramatic difference in body size between males and females is known as sexual dimorphism, which can be observed today only in baboon populations living in tropical savannas. Sexual dimorphism is absent in monogamous species but is always associated with polygamy, representing an adaptation of males competing for females.

Australopithecus boisei