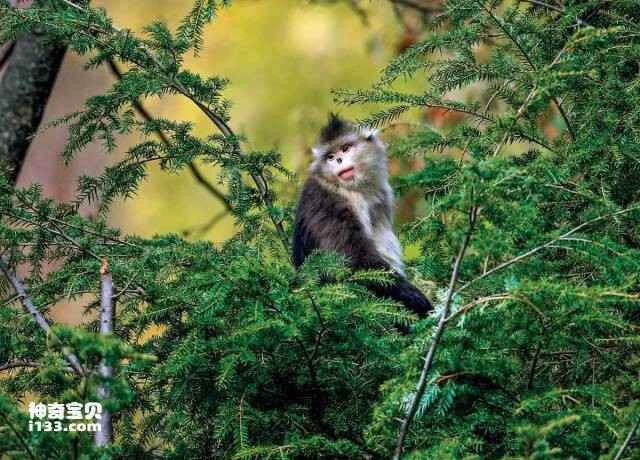

In the Yunling Mountains, at an altitude of 2,500 to 5,000 meters in the Hengduan Mountains on the southern edge of the Himalayas, lives one of the world's most precious primates—the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey. These are Class I protected wild animals in China and are known as the "Snowy Spirits." As a national treasure on par with the giant panda, the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey sports a distinctive hairstyle with a pointed black crest and "fiery red lips"—it's truly unique!

There are currently five species of golden snub-nosed monkeys in the world: the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey, the Guizhou snub-nosed monkey, the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey, the Burmese snub-nosed monkey, and the Vietnamese snub-nosed monkey. The Yunnan snub-nosed monkey currently has only 13 natural populations remaining, totaling less than 3,000 individuals.

Among monkeys, the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey is a star of the slightly chubby world. Both males and females have large bellies and round waists, making them look almost pregnant. But this isn't because they don't like to exercise. Their large bellies are mainly due to their diet of lichens, broad-leaved tree buds and leaves, and bamboo shoots, all of which are relatively low in nutritional value. To ensure they get enough energy and nutrients, the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey must eat constantly, which may explain their round bellies. With their good looks, even being a little chubby is a kind of celebrity charm.

The Yunnan snub-nosed monkey is so rare and endangered, not only due to hunting destruction, but also because habitat destruction has led to food shortages. Let's talk about their diet.

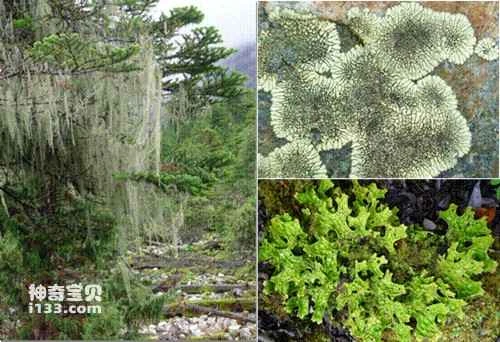

The habitat of the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey is mainly covered with tree species such as fir (Abies ferreana), Chinese fir (Abies delavayi), alpine oak (Quercus semecarpifolia), and rough-barked birch (Betula utilis). Lichens and mosses often grow on these tall trees.

Research indicates that, in addition to consuming the tender leaves, flowers, fruits, and seeds of these plants, lichens make up about 60% of the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey's diet. Surveys show that they consume over a dozen species of lichens, including *Usnea longissima* and *Lobaria yunnanensis* (the fact that Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys eat *Lobaria yunnanensis* is indeed a novel observation, not mentioned in previous reports; the photos provided here are firsthand evidence). Especially during the winter when heavy snow closes off the mountains, lichens are the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey's sole food source.

The distribution areas of these two lichen species are mainly concentrated in Deqin, Weixi, Lijiang, Jianchuan, and Zhongdian in Yunnan Province, and Kangding in Tibet, which is basically consistent with the current distribution of the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey. It can be inferred that the distribution areas of these lichen species consumed by the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey are closely related to its migration routes. Historical records indicate that the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey had a wide distribution area in ancient China, but due to the impact of human activities and habitat destruction, it has gradually retreated to a corner bordering Yunnan and Tibet for survival.

Speaking of lichens, we must delve into the details of this fascinating creature. Everyone is probably curious about what makes them so appealing to the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey. In fact, they share a similarly complex history with the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey.

Many people mistakenly believe that lichens are "moss," and it's understandable that they think so. This has historical roots. As early as 1753, Linnaeus, the founder of taxonomy, published his Species Plantarum, in which he grouped lichens as a genus with mosses and algae, placing them in the order Algales of the plant kingdom.

For a considerable period, people viewed lichens as a single type of green plant. The Swedish physician Acharius, hailed as the father of lichens, discovered many new species of lichens and established numerous new genera in the early 17th century, but at that time he did not understand what lichens actually were.

It wasn't until 1867 that German scientist Schwendener revealed the duality of lichens—that they are symbiotic organisms composed of fungi and algae, rather than single green plants. This was a major leap forward in human understanding of lichens. The fungi and algae within the lichen are closely related; the algae provide food for the fungi, while the fungi protect the algae. They form a single entity, and once separated, neither can thrive in nature, much like inseparable lovers. Therefore, scientists have long regarded the fungal-algae symbiosis in lichens as a model of mutualistic symbiosis.

Fruticose lichens, scale lichens and leaf lichens

Nature has created a diverse array of lichens, each with its own unique shape and vibrant colors. There are brightly colored crustacean lichens that grow on rocks, scale-like lichens that grow on the soil surface, and leaf-like and branch-like lichens that grow on tree bark. The lung tissue eaten by the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey is a leaf-like lichen, while Usnea is a branch-like lichen.

Lichens are small in size in nature, yet they are hailed as "environmental indicator organisms." This is because lichens are very sensitive to environmental pollution, and their growth is very slow. Once faced with environmental damage, it means a crisis of essentially non-renewable resources for them.

Not only does it provide food for animals like the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey, but it also plays a vital role in plant population succession. The lichen acids produced during lichen growth erode and weather the substrate, gradually altering its surface environment through the accumulation of dust and the invasion of other microorganisms, thus creating the essential growth conditions for mosses, ferns, and other higher plants. Therefore, lichens are also known as "pioneer organisms of the land."

Besides their medicinal uses, lichens have made numerous contributions to humankind. They are widely used in cosmetic fragrances, antibiotic raw materials, and traditional clothing dyes. They also have a long history of medicinal use in China, documented in ancient texts such as the *Mao Shi Zhu Shu* and the *Compendium of Materia Medica*. Modern works like *Chinese Medicinal Lichens* and *Chinese Medicinal Spore Plants* record nearly 100 species of medicinal lichens in China. In Yunnan alone, over 80 species of edible and medicinal lichens are known to be consumed. In Yunnan, the *Usnea* and lungs, favored by the Yunnan golden monkey, are also collected and eaten, considered delicacies.

Like the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey, lichens face the most dangerous and devastating human destruction. With deforestation and the expansion of cities and industry, some lichen species are already on the verge of extinction. As lichen resources dwindle, many animals that feed on lichens, like the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey, will face food scarcity. This will not only force them to migrate their habitats but also cause population changes due to food shortages, ultimately impacting overall biodiversity. Therefore, the rational protection of lichens and other natural resources is of paramount importance.

The Yunnan snub-nosed monkey is the highest-altitude primate in the world besides humans, and is considered the most beautiful and noble monkey in the world. Lichens are the cornerstone of ecological balance, the colorful garments protecting the earth. Today, they are being relentlessly destroyed; their home is also our home. This secret garden of nature needs our collective efforts to protect and nurture it.