When comparing plants and animals, people often tend to think of animals as the stronger and more intelligent ones: because plants are rooted in the earth, cannot move freely, and are preyed upon by animals. But is this really the case? Can plants—considered the weaker party—successfully turn the tables?

I love carnivorous plants, not only because of their cool hunting skills and beautiful appearance, but also because these plants are always staging stories of underdog triumphs. The dramatic tension arises when the roles of predator and prey are reversed, and animals become food for plants. Carnivorous plants are undoubtedly the most glamorous stars in the plant kingdom, able to perform this drama so brilliantly on the stage of nature.

To forge a path through adversity

Insectivorous plants are a group of plants that can capture and digest insects and arthropods, comprising approximately 600 to 750 species. Interestingly, although they all share the common skill of catching insects, they are quite different in phylogeny, originating from 10 different families and 17 genera in the plant kingdom.

Driven by their respective survival pressures, carnivorous plants have unanimously embarked on a path of insectivorous survival through their own unique methods. On the vast earth, not every inch is fertile soil; many places are sandy wastelands, cold slopes, and nutrient-deficient waters, creating harsh and barren environments that pose numerous obstacles to plant survival. For example, some seemingly lush swamps, due to their long-term acidic environment, have soils rich in organic matter that are difficult for bacteria to decompose into nutrients suitable for plant growth. Even in tropical rainforests, often called a "paradise for flora and fauna," although nature is never stingy with sunlight and rain, the competition for limited space and resources between tall trees and dense vines still creates fierce competition for survival among various plants.

The long-term scarcity of resources led some plants to learn to use insects and other small animals, which are delicious and rich in protein, as a new source of nutrition. However, while animals are tasty, they are not lambs to the slaughter. Without strategy and tactics, insects will not let themselves be disposed of! Fortunately, nature is quite fair, giving these plants, under immense survival pressure, the opportunity to evolve freely. Along the long path of evolution, these plants, living in different environments, have all developed the best, most effective, and most effective insect-hunting tools—insect traps. These traps, though different in form, are all ingenious, captivating countless scientists and plant enthusiasts, inspiring endless exploration.

One wrong step and you're plunged into an abyss—a falling trap insect catcher

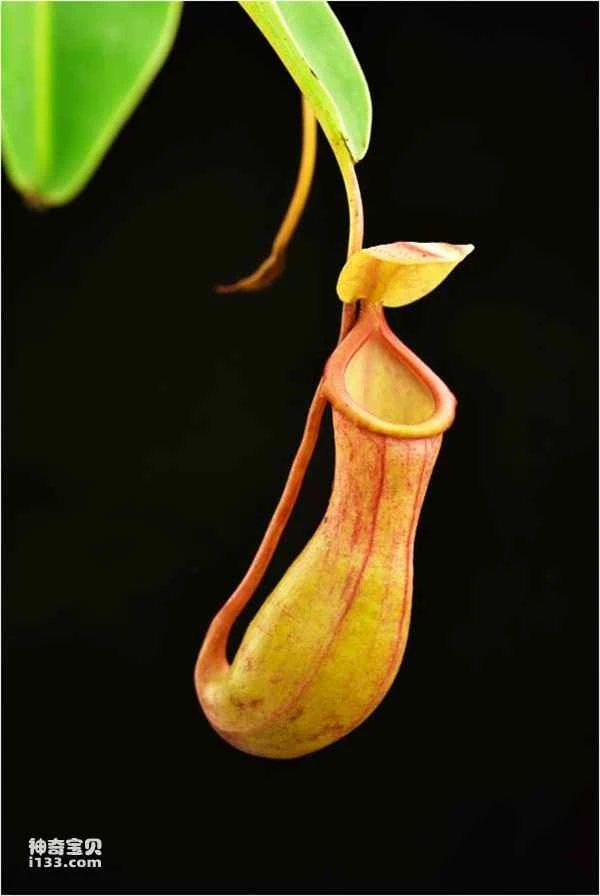

There is a type of carnivorous plant that can trap insects without moving its body or leaves. Its ingenious trap is a "trap" that the insects fall into and cannot climb out. This "trap" can be formed entirely of the plant's leaves. For example, some bromeliads utilize the plant's shape to form a bucket-like structure with all their leaves. The leaves at the top of the trap are extremely smooth; if an insect falls in while probing, it will be killed and decomposed by the acidic liquid containing digestive enzymes at the bottom. Other carnivorous plants have more sophisticated drop-trap structures, such as those in the genera *Nepenthes*, *Pitcher Plant*, and *Nepenthes*, where individual leaves are specialized to form cage-like trap structures. To improve the trap's efficiency, these carnivorous plants constantly refine their traps, making the entire trap system a complex and highly efficient insect-hunting machine.

To attract more insects, these plants use specialized leaves to create pitcher-shaped traps that secrete sweet nectar at the opening. Mimicry is also a common technique; for example, many pitcher plants use vibrant, varied colors at the top of their traps to mimic flower shapes, increasing insect visits. Many pitcher plants are also masters of scent, mimicking floral aromas by releasing floral-scented substances to attract insects. While the mechanisms and forms of mimicry in carnivorous plants have been a subject of debate among scientists, there is no doubt that this "disguise" greatly enhances the trap's predation efficiency. However, successful attraction is only the first step; successfully capturing and trapping prey is also crucial. These carnivorous plants often leave a platform for flying insects to land on. When visiting insects land on the platform and begin sucking the nectar provided by the trap, they gradually move towards the smooth edge of the trap. Below the edge, densely distributed downward-guiding hairs ensure that if the greedy little creatures stumble, they will face certain death. Ultimately, in the highly efficient digestive fluid filled with digestive enzymes and the remains of their companions, the insects are gradually decomposed, becoming a "nutritional haven" for carnivorous plants.

The pitcher-shaped trap of the red bottle plant

A Deadly Kiss – Sticky Insect Trap

As the name suggests, sticky insect traps are created by plants secreting glue to trap their prey. This is one of the most common hunting methods among carnivorous plants. Plants in genera such as *Viola*, *Pteris*, *Desmodium*, and *Spicata* often secrete large amounts of thick, sticky, or water-drop-like glue or resin on their surface, which can firmly adhere to and capture insects that come into contact with them. Because these traps often cover the entire plant, and many species also have odor mimicry mechanisms, releasing scents that attract insects, they are highly efficient at trapping prey.

Drop traps, with their relatively enclosed pools, protect their prey from easy theft. Plants with sticky traps are entirely different, facing the risk of food being stolen by other larger insects or animals. Rain and strong winds also affect their ability to gradually decompose and absorb insects. But don't worry, many species of sticky trap carnivorous plants have learned to tightly wrap and absorb their prey by curling their leaves and tendrils after successfully capturing it—a process that typically takes anywhere from a few minutes to several days. Some species, such as the acorn sundew, have tendrils that act like ingenious switches, instantly curling and closing towards the center of the leaf to tightly envelop the prey.

Aphrodite (Insectivora argenteum) and Drosera (Drosera esculenta)

Unique Design – Lobster Basket-Shaped Insect Trapper

Some of these insect traps are similar to drop traps, such as those found in the genera *Pitcher Plant* and *Pitcher Parrot*, but they employ a more sophisticated trapping mechanism. Unlike the wide entrance of drop traps, the specialized, modified leaf tips almost close to form a spherical cavity, leaving only a small entrance. The ingenuity of these traps lies in their exploitation of the insect's nature and weaknesses, similar to the principle behind using lobster baskets to catch lobsters.

Like many pitcher plants, the lobster basket-shaped insect trap uses its colorful and varied leaves and sweet nectar to lure insects. Once attracted, the insects, following the nectar, crawl to the small entrance and, lured by their craving for food, are drawn into the hole. Inside, it resembles a brightly colored little room. Unable to find an exit in this colorful, psychedelic world, the insects can only follow the path provided by the pitcher plant, thus finding no way to escape.

Cobra pitcher plant

Rare Qigong – Suction-type Insect Trapper

This is a patented insect-trapping technology of the aquatic carnivorous plant *Utricularia bladderwort*. Bladderworts are typically small, forming tiny, vacuum-like chambers no larger than 10 millimeters in size underwater. When food touches a specific switch, it is instantly sucked into the chamber by air pressure and slowly absorbed by the bladderwort. Bladderworts are a type of aquatic plant widely distributed in most parts of the world and are a type of carnivorous plant very close to our lives. Unfortunately, their individual size is usually very small, and the hunting process in the water often ends in a fraction of a second. If we slow down this process and observe it closely, we can see the incredibly skillful hunting techniques of these insect traps.

Bladderwort

A brilliant and ingenious trap – the animal trap insect snare

Carnivorous plants with trap-like snares are perhaps the closest to the carnivorous plants in people's imaginations; many man-eating plants in movies and comics have similar abilities. Once an animal touches a certain switch, a large mouth or a trap full of sharp spikes suddenly closes, trapping the careless animal and quickly eating it. The origin of this imagination is likely related to the real-life Venus flytrap.

Over its long evolutionary history, the Venus flytrap has developed a trap-like structure—an insect trap: two crescent-shaped, spiked structures with three delicate, sensitive hairs inside. If prey touches two of these hairs consecutively within a certain timeframe, the trap-like leaves close rapidly within a third of a second, the spiked edges interlocking tightly to form a cage-like structure that firmly locks the prey inside. Gradually, the two leaves adhere completely due to the insect's continued movement and stimulation within the "cage," ultimately killing and digesting the insect.

The trapping process of an animal-shaped snare is not only spectacular but also incredibly intelligent. The opening and closing mechanism of the snare, adorned with three barbs, cleverly distinguishes between disturbances caused by wind and rain and the actual intrusion of an insect. The sharp spines along the leaf margins filter prey when the snare closes; if the insect is too small to provide enough nutrients for the snare to close, it can escape, allowing the snare to reopen and await a larger prey.

Venus flytrap

semi-carnivorous plant

Nature is amazing. Besides the carnivorous plants that people know, there are many other plants on the path to becoming carnivorous. Some carnivorous plants seem to have reached the end of their carnivorous journey, but then turned back halfway.

Many plants can trap insects, such as the dragon fruit (Passiflora edulis) of the Passifloraceae family. During the fruit's growth period, a sticky, net-like structure similar to that of a sundew forms around the fruit to trap small insects. In recent years, scientists have confirmed that this structure not only traps insects but also secretes digestive enzymes to digest and absorb its prey. However, the dragon fruit is not a traditional carnivorous plant. Research has found that this trapping mechanism and structure primarily protect the fruit from insects. Scientists speculate that during the evolutionary process, if the environment was nutrient-poor, this insect-trapping mechanism might have been further enhanced, evolving into a more sophisticated and efficient trap, moving the dragon fruit further towards carnivorous behavior.

There are many other plants like these that can trap insects, such as those in the genera *Plumbago*, *Eriocaulon*, some bromeliads, and *Dipsacus*, all of which possess varying degrees of insect-trapping abilities. However, perhaps because they cannot secrete digestive enzymes, or because their trapping mechanisms are not sufficiently specialized, insect-trapping behavior plays a relatively minor role in their growth and reproduction, and these plants are not included in the traditional list of carnivorous plants. They seem to be on different paths to becoming carnivorous plants.

Dragon fruit

Interestingly, even after reaching the end of their carnivorous path, some carnivorous plants seem to have "changed their minds," discovering that carnivory isn't necessarily the best option. While some carnivorous plants already possess excellent predatory organs, they have chosen a seemingly reversed path in the long course of evolution. For example, the famous carnivorous plant family, *Nepenthes appleensis*, has chosen a "vegetarian" path. Although it still possesses a pitcher-like trap, it no longer secretes protein-digesting enzymes inside; instead, it opens its mouth wide upwards, relying on digesting and absorbing fallen leaves to supplement its nutrition.

Other well-known large pitcher plants, such as *Nepenthes laurentii* and *Nepenthes kingpinus*, likely chose the path of "feeding on dung." Their traps secrete nectar to attract small animals such as tree shrews to lick it. *Nepenthes laurentii* and *Nepenthes kingpinus*, with ulterior motives, then provide natural "toilets," using the animal droppings as their own nutrients.

Pitcher Plant (Nepenthes wanghou)

One Trap, One World – Symbiosis

On the path of plants becoming carnivorous, they are often not alone; choosing suitable animal partners can bring unexpected benefits to both. Many carnivorous plants have found numerous such partners during their long evolutionary process, greatly enhancing their carnivorous lives. This mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship is widespread among carnivorous plants.

Symbiotic relationships are particularly prominent in pitcher plants (Nepenthes, Nepenthes, and Bromeliaceae). Private pitcher-like traps provide a convenient environment for many animals and an opportunity for mutual benefit with carnivorous plants. Some pitcher plants cannot secrete digestive enzymes or have very few, making it impossible to directly break down their prey. However, they can solve this problem effectively with the help of benthic organisms residing in the pitcher. Some midge larvae and North American pitcher mosquito larvae eat and break down their captured prey into particles, which are then further decomposed by bacteria in the pitcher into nutrients that the pitcher plant can directly absorb—both the landlord and tenant benefit. The herbivorous pitcher plant, *Nepenthes appleensis*, has an even more miniature world in its pitcher. Fallen leaves become food for bacteria and herbivorous insect larvae, which in turn become food for tadpoles and giant mosquito larvae, while the *Nepenthes appleensis* absorbs the nutrients in the process. This small world within the pitcher becomes a self-contained ecosystem, even giving rise to many species unique to this food chain.

Ants are among the most common prey of some pitcher plants, often attracted by the nectar secreted by the pitchers and thus becoming prey. However, a species of carpenter's ant has cleverly chosen to establish a mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship with the Borneo pitcher plant: the hollow tendrils of the pitcher plant provide shelter for the ant, while the ant feeds on the trapped large insects or mosquito larvae. Superficially, the ant seems to be plundering some of the plant's prey, but both sides benefit, thus achieving a dynamic balance. If the pitcher captures large prey, the excessively large carcass may exceed the pitcher's digestive capacity, and the carpenter's ant helps carry the extra prey, thus ensuring the pitcher's digestive system remains intact. The ant also cleans the pitchers for the pitcher plant, keeping their rims smooth and protecting the pitcher from other animals; in return, the ant enjoys a relatively peaceful home.

The butterwort (a carnivorous plant) is a perfect partner for the tussock bug in their hunt. The butterwort can grow several meters tall, its branches covered in a powerful, resinous sap, making it extremely efficient at trapping insects. However, it cannot secrete digestive enzymes to digest its prey. But don't worry, through long-term evolution, the butterwort and the tussock bug have perfectly solved this problem through deep cooperation. The tussock bug has evolved a unique waxy coating that prevents it from getting stuck in the butterwort's resin, allowing it to move freely through the treacherous slime forest. Other insects caught by the butterwort become easy prey for the tussock bug. In return, the tussock bug's digestive system digests its prey and excretes easily absorbed, highly efficient organic fertilizer onto the butterwort's branches and leaves for the bug to absorb.

Insect Hiro

In fact, the relationship between carnivorous plants and their prey insects is often quite complex, with much still needing further research. Many fascinating phenomena fascinate and fuel ongoing debate among meticulous scientists. For example, some pitcher plants are believed by many scientists to have a mutually beneficial relationship with their prey: the pitcher plants provide some insects with a rare and highly efficient energy drink in swamps—nectar—while the entire insect population pays only the price of a small number of individuals, providing the pitcher plants with a source of nitrogen. Both sides are providing a much-needed commodity, making this seemingly dangerous predation a win-win situation!

Of course, the relationships between plants and animals on the path to carnivorousness are not always harmonious; there are also many seemingly one-sided, self-serving relationships: for example, many ants will unceremoniously and quietly steal the prey caught by butterworts, leaving no nutrients behind; green cat spiders can directly drag out and eat insects that have fallen into pitcher plants; and pitcher plant spiders have even learned to lurk near pitcher plant traps and capture insects attracted by the traps. According to current research, these behaviors do not seem to bring any substantial benefits to the plants.

The Road to the Future

The evolutionary path of carnivorous plants is extremely fascinating. Plants from four different orders—Bromeliads, Nepenthes, Pitcher Plants, and Gynostemma—have all evolved trap structures with similar appearances and functions, despite varying environments and origins. However, the genera *Drosera* and *Venusa*, belonging to the same family (Droseraceae), have diverged significantly from their parent genera *Drosera*, evolving in different directions with vastly different appearances and predation methods. The most popular sticky insect traps, originating from genera such as *Drosera*, *Drosera*, *Drosera*, and *Drosera*, despite their diverse families, share similar predation methods and many morphological characteristics. As for the future, the evolution of carnivorous plants still has a long way to go, with many more hunting methods and mechanisms yet to be explored.

Human knowledge of carnivorous plants is still very limited, and many species may become extinct before we can fully understand them. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), more than half of carnivorous plants are threatened with extinction. These threats come from various sources, including changes in natural ecosystems and human activities. For example, population growth and land reclamation are constantly encroaching on carnivorous plant habitats; environmental pollution also destroys their habitats; and the hobby of some plant enthusiasts cultivating carnivorous plants leads to the digging up or destruction of large numbers of wild carnivorous plants. All of these factors could lead to the extinction of carnivorous plant populations.