Spiders and other arachnids

Spiders are ancient animals, dating back millions of years. They have been with us all along, an ancient source of fear and fascination. Abundant and widely distributed, they are natural controllers of insect populations.

Spiders are arachnids, not insects, but both spiders and insects belong to the largest group of animals on Earth—arthropods (Ancient Greek: arthro = joint, podos = having feet)—animals with a hard exoskeleton and jointed limbs.

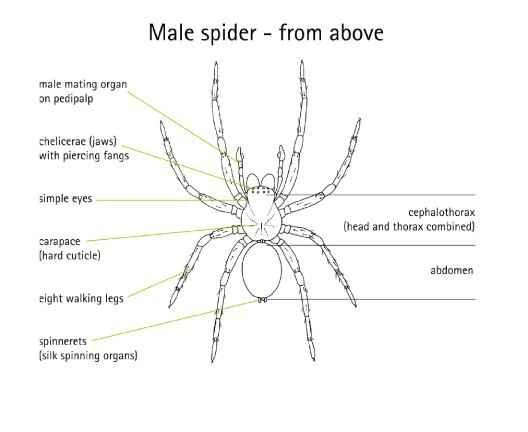

Spiders have:

The two main parts of the body, the head and the chest, are collectively called the cephalothorax and abdomen.

Eight walking legs

Simple eyes; spiders usually have eight eyes (some have six or fewer), but few have good eyesight.

Jaws adapted for tearing or piercing prey

A pair of tentacles

Abdominal silk-producing organs

The opening of the genitals in the anterior abdomen.

Spider body parts

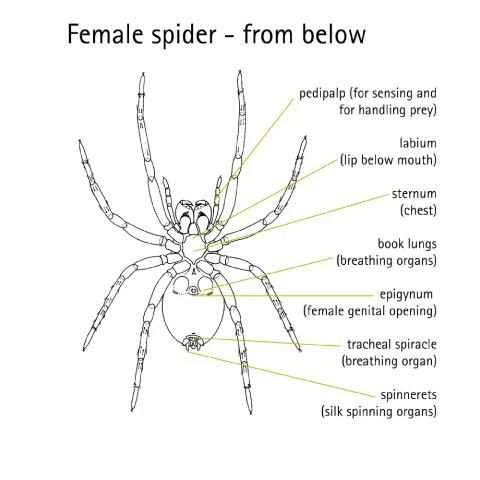

A spider's body is divided into two parts. The head and thorax, which contain eyes, mouthparts, and legs, are fused together to form the cephalothorax. It is connected to the second body part (the abdomen) by a slender waist (flower stalk), which contains silk-spinning organs (spinnerets), a genital opening, and respiratory organs (book lungs and/or trachea).

head and chest

The cephalothorax is covered by a hard, keratinous plate called the carapace—much like the hard shell of a crab.

Lateral part of the head and chest

Simple eyes - usually eight (sometimes six), typically arranged in two rows along the front of the carapace (although the arrangement and size of the eyes vary).

The central depression – the depression in the middle of the carapace – is the internal attachment point of the pectoral muscles.

Mouthparts – Two large jaws (chelicerae) with sharp, pointed teeth, and two small keratinous plates (flat keratinous plates) on the underside behind the lower jaw – one upper plate, the labial flap (upper lip), hidden behind the lower lip plate (lower lip), clearly visible from behind the lower jaw. These two plates form the top and bottom of the tubular mouth, which opens behind the jaws. On the sides of the lower lip are a pair of plate-like maxillae, each with a row or piece of food-cutting teeth at its anterior end.

Palpations—help with food processing, touch, and taste; in male spiders, pedipalps are modified into mating organs.

Legs - Four pairs of jointed legs with two to three terminal claws. Two-clawed spiders are hunters (e.g., jumping spiders, hunter spiders, ground spiders), and most of their legs have thick brushes (scythes or claw clusters) at the ends - these enhance traction on smooth or sloping surfaces (such as leaves or tree trunks). Many three-clawed spiders are web-weaving spiders, often with modified claws and hairs for handling silk (e.g., ball web-weaving spiders, glue-footed spiders, lace spiders).

The inner side of the cephalothorax has

Muscles – help move the jaw and limbs. Muscles from the limbs, intestines, and shell appendages are all connected to the central sternum (internal non-chitinous skeletal plate).

Brain ganglia - a large amount of nerve tissue.

Venom glands - produce venom to kill prey

A muscular stomach pumps liquid food into the esophagus (food duct) and pharynx (throat) and moves it along the intestines. The stomach forms at the end of the foregut. Diverticula (growths) extending into the legs are also present in the cephalothorax.

abdomen

The abdomen is usually covered with a thinner or more flexible cuticle – this allows it to expand during feeding or egg development. A narrow waist or pedicel that separates it from the cephalothorax allows the abdomen to move, for example, during silk spinning and mating displays.

There is on the outer side of the abdomen

The book's lung cover—protects the delicate organs inside.

The genital opening, or genital opening, is where eggs or sperm are released, located in a genital groove between the first pair of book lungs. Most female spiders have another separate, patchy copulatory opening, the external female organ.

The spinneret (silk spinning organ) – usually four or six – and the terminal anal tubercle, where the intestines end at the anus.

Inner abdomen

The lungs in this book are respiratory organs. Small openings called stomata lead to air-filled cavities into which thin, leaf-like plates of the book lung extend, like rows of pages. The outer surface through which air passes is covered by a very thin cuticle, from which nail-like supports extend to prevent the plates from collapsing. Blood (hemolymph) circulates within the plates, and gas exchange between blood and air occurs on the thin walls of the plates. Mygalomorph (and some araneomorph) spiders have two pairs of book lungs. Most arachnids have only the first pair, with the second pair replaced by tiny epidermal tracheae that separate internally for more efficient gas exchange. Some tiny spiders living in damp, sheltered habitats lack respiratory organs; gas exchange occurs directly through a thin cuticle.

Silk glands - produce liquid proteins that make silk.

Reproductive organs (ovaries or testes).

The heart – located on the midline of the body, can be seen beating through the stratum corneum of the back. Blood circulation is open, meaning blood vessels run from the heart into the body space, bathing tissues and organs in blood, which then gradually circulates back to the heart.

The hindgut and its diverticulum – the place where nutrients are absorbed into the tissues. The hindgut has a sac in which the excretory organs, called Malfige tubules (the spider's "kidneys"), open.

Chin and fangs

In mygalomorph spiders (trapdoor spiders and funnel-web spiders), the large mandible protrudes forward from its base and folds backward beneath it, alongside their fangs. To bite prey, these spiders must raise the front of their bodies, allowing their fangs to open like a pair of daggers and strike downwards. In more common spider species (redback spiders, wolf spiders, etc.), the mandible hangs vertically below the front of the carapace. The fangs hinge laterally, interlocking like pincers. This is a more efficient way to capture and manipulate prey, especially on the web.

Spider skin

Like other arthropods, spiders are covered by a more or less hard "skin" or keratinous layer (exoskeleton) made of protein and chitin. The spider's keratinous layer consists of several layers, the outermost being the hardest and covered with a thin layer of wax that helps reduce water loss. The keratinous layer provides internal attachment points for muscles, helping to regulate blood pressure. While its hard exterior provides protection, the keratinous layer must still house the spider's sensory organs—in the form of various types of nerve-innervated (supplying) hairs and pits, as well as the eyes. The keratinous layer even extends inwards, covering the foregut (mouth to stomach) and hindgut, the trachea (breathing) tube, and the female's sperm storage organ (spermatic receptacle).

For a spider to grow, its entire cuticle must be shed periodically; this process is called molting. First, a larger, new cuticle grows beneath the old one. The old cuticle splits open, and the spider emerges. The new cuticle is very soft, and most spiders won't move until it hardens.

Spider skeleton

A spider's exoskeleton surrounds a blood-filled body space. Within this semi-rigid space, blood pressure can fluctuate through changes in heart rate or the contraction and relaxation of muscles, particularly the strong pectoral muscles. The cuticle and blood together form a pressurized unit called the hydrostatic skeleton. This is crucial for maintaining body shape (expansion) and function.

Life and Death

The ability to regulate blood pressure is crucial for various functions, including molting and locomotion. During molting, an increased heart rate leads to elevated blood pressure, which helps open the fragile cuticle. During locomotion, limb extension is primarily achieved through the contraction of strong pectoral muscles. This contraction increases blood pressure in the thoracic cavity, causing the limbs to extend outward. This explains why spiders have many flexor muscles for bending their limbs inward, but fewer extensor muscles for extending them outward—they simply don't need as many. This also explains why the legs of injured or dead spiders are always bent inward—they can no longer control their blood pressure, allowing the powerful flexor muscles to dominate and pull the legs under their bodies. This "death posture" is mimicked by spiders when they fall from their webs to escape predators—only this time, their legs are deliberately bent while feigning death.