The fossil of *Dendrobium solitarius*, discovered in southern Africa, is the oldest bacterial fossil ever discovered by scientists and the oldest representative of all paleontological fossils. *Dendrobium solitarius* is a prokaryote, dating back 3.2 billion years. Because the earliest life forms on Earth, such as *Dendrobium solitarius*, are very primitive single-celled organisms, even when fossilized, they are extremely light, fragile, and easily broken. Therefore, scientists had long struggled to find other reliable fossils of these primitive life forms.

Later, when some scientists analyzed the formation of weathered banded iron ore in sedimentary rocks, they discovered that this type of iron ore was formed by an ancient microorganism called iron bacteria; moreover, the iron bacteria that formed these iron ore deposits could be traced back to as far as 3.2 billion years ago.

Iron bacteria share common characteristics with other bacteria: they are single-celled organisms with diameters ranging from a few micrometers to tens of micrometers, and are prokaryotes without a nucleus, meaning they can only be observed under a microscope magnified thousands of times. Some iron bacteria have oval or rod-shaped cells that connect to form rather long filaments; some individual iron bacteria are themselves thin, long filaments. Others are spherical, arc-shaped, or rod-shaped with stalks or branches; still others form small nodules, ribbons, or spirals. All these iron bacteria are encased in a thin layer of "armor"—a sheath.

Iron bacteria ingest inorganic substances such as iron and silica during their life processes. In swamps and lakes, iron usually exists in the form of soluble ferrous hydroxide. After being ingested by iron bacteria, it is oxidized into insoluble ferric oxide through enzymatic catalysis within the bacteria.

These insoluble iron compounds and silicates, among other inorganic substances, are secreted by iron bacteria, forming a sheath primarily composed of iron. Interestingly, the sheath of iron bacteria is often several times or even tens of times larger than its body. Iron bacteria can move back and forth within the sheath, and sometimes even extend beyond it to rebuild a new one. The shed sheath then settles in water, accumulating into iron ore. You might not imagine that these iron bacteria, living millions of years ago, have become skilled artisans in iron production through this lifestyle, providing humanity with extremely rich iron ore resources today.

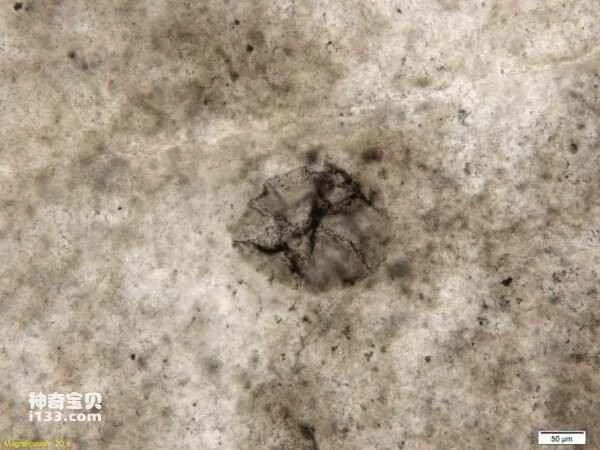

Scientists have discovered banded iron ore layers in Precambrian sedimentary rocks dating from 1.8 billion to 3.2 billion years ago in the United States, Canada, the former Soviet Union, Australia, India, and southern Africa. These layers commonly contain iron bacteria fossils. Iron bacteria fossils can be observed by grinding the rocks or ores into thin slices and examining them under a high-magnification biological microscope or electron microscope.

Because research on ancient iron bacteria fossils is still insufficient, only a dozen or so species have been discovered so far. They are somewhat similar to modern iron bacteria, but also different. Some of these species are extinct. Of course, the species of that time are by no means the same as the modern species. For example, the ancient filamentous iron bacteria are very similar to modern filamentous iron bacteria; they both have a sheath, but the ancient ones were much larger than the modern ones.

Iron bacteria are mostly aerobic microorganisms, but they require very little oxygen. Scientists speculate that the Earth's atmosphere 3.2-3.4 billion years ago was highly reducing. At that time, there was almost no oxygen in the atmosphere, only carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrogen. Around 3.2-3.1 billion years ago, cyanobacteria appeared. For the next 2.7 billion years, these cyanobacteria absorbed carbon dioxide from the original reducing atmosphere, used chlorophyll for photosynthesis, produced free oxygen, and released it into the atmosphere. This gradually increased the oxygen content in the atmosphere, providing favorable living conditions for aerobic iron bacteria. This ensured that they could continuously absorb ferrous hydroxide from water and oxidize it into insoluble ferric oxide, which would then be deposited at the bottom of the water.

It is evident that the bacteria that often cause panic and misunderstanding today not only laid the biological foundation for the evolution and development of the entire biosphere in the years that followed, but also some of their molecules accumulated indispensable mineral resources for the progress of intelligent life—human beings—to this day.