Recently, some media outlets have again mentioned bats and the 2002 SARS outbreak, because bats carry SARS-like viruses. As a result, bats have once again been demonized, and people are terrified of them. We, as young scholars who have long studied bats (from five different cities, names listed at the end of this article), would like to say a few words in defense of bats from a different perspective.

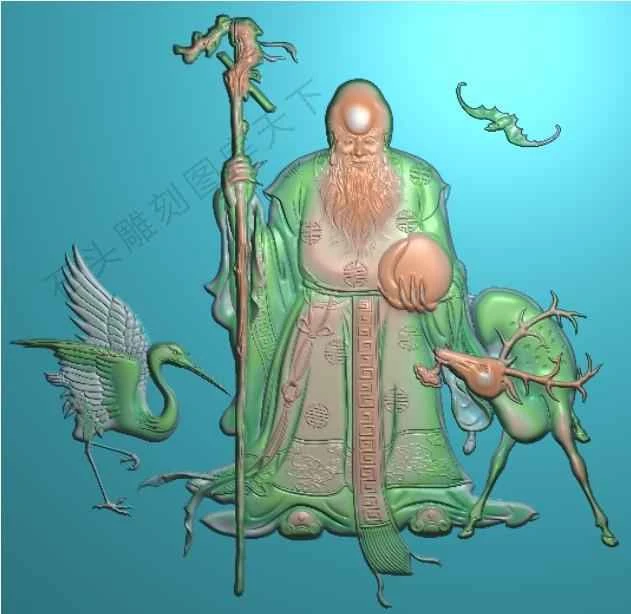

1. In traditional Chinese culture, bats are symbols of good fortune, longevity, auspiciousness, and happiness.

Because the word for "bat" (蝠) is a homophone for "fortune" (福), bats were used to represent good fortune, thus personifying the character "福". Consequently, bat motifs appeared extensively on ancient buildings, decorations, doors, windows, furniture, silk, porcelain, jade, calligraphy, paintings, clothing, shoes, and hats. For example, two bats together symbolize "double fortune"; five bats represent "five blessings arriving at the door"; a child catching a bat and putting it in a bottle signifies "five blessings of peace"; a bat landing on paper symbolizes "bringing fortune home," and so on. Among these, "five blessings arriving at the door" is the most widespread.

Auspicious patterns related to bats have transformed the image of bats from their ugly appearance and mysterious behavior in real life into something exceptionally beautiful, becoming a symbol of good fortune and auspiciousness. For thousands of years, bat patterns have been beloved and hold an extremely important place in Chinese auspicious patterns. The patterns are diverse, and the bat forms vary greatly, ranging from figurative to abstract. Some are combined with graphics, while others echo text, creating a delightful and interesting effect.

" Five Blessings Arrive at the Door" Bronze Ware (Image from the Internet)

2. Bats are longevity stars, holding the secret to human longevity.

Health and longevity have always been the ultimate goals pursued by humankind. From Qin Shi Huang sending Xu Fu to sea in search of the elixir of immortality to modern-day cryogenics, all are examples of "tough guys" taking action in pursuit of health and longevity. Animal lifespan is often closely related to size; larger animals typically live longer than smaller ones. For example, African elephants can live up to 70 years, while ordinary mice usually only live one to three years. Humans are relatively long-lived animals, typically living four times longer than other animals of similar size. Surprisingly, although bats are small, they can live very long lives. Some bats can live up to 40 years, eight times longer than mammals of similar size. If we could live as long as bats, converted to size, we humans could live up to 240 years. Scientists have currently confirmed 19 mammal species with lifespans longer than humans, one of which is the longevity star, the naked mole-rat; the other 18 are all bats. In fact, many bat species are very long-lived; within the entire bat group, longevity may have originated independently at least six times. Recently, researchers have also studied the molecular mechanisms of bat longevity. They found that, unlike other mammals or short-lived bats, the telomeres of long-lived bats do not shorten with age, and genes related to DNA repair and tumor suppressor genes have undergone strong adaptive selection in long-lived bats. Although our understanding of the mechanisms of bat longevity is not yet comprehensive and in-depth, with the introduction of new technologies and methods, scientists will surely achieve greater breakthroughs in the future, providing a new theoretical basis for achieving the goal of healthy longevity in humans. In particular, as China gradually enters an aging society, studying the mechanisms of bat longevity provides a new research avenue for extending healthy lifespan, making it even more urgent and significant.

Sculpture of the God of Longevity (with a bat in the upper right corner) (Image from the internet)

3. Bats have an extremely low probability of developing cancer, making them a star animal for studying cancer-suppressing mechanisms.

Globally and domestically in China, cancer is the second leading cause of death after cardiovascular disease. While treatments for certain types of cancer have been developed, most come with serious side effects. In particular, almost all treatments are only effective against early-stage cancer; for late-stage cancer, even the most skilled doctors are helpless. One of the ultimate goals of cancer research is to develop methods for treating or preventing cancer that are both highly effective and free of toxic side effects. Mice and rats are commonly used animal models for cancer research in laboratories. These animals have short lifespans, reproduce rapidly, and are highly susceptible to cancer, making them very useful for simulating different types of human cancer and testing various treatments in the short term. However, these tumor-susceptible animals are ineffective in understanding anti-cancer mechanisms. Fortunately, over long-term evolution, different animals have developed differences in tumor susceptibility. Researchers have found that, unlike mice and rats, the naked mole-rat in Africa is not only long-lived but also possesses extremely strong cancer resistance. The cells of the naked mole-rat can secrete large amounts of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid, a substance that effectively inhibits unlimited cell proliferation. Unrestricted proliferation is the most fundamental characteristic that distinguishes cancer cells from other normal cells. Therefore, this mechanism may be key to the naked mole-rat's ability to resist tumor development. The blind mole-rat is another animal with tumor-resistant capabilities, but its anti-cancer mechanism differs significantly from that of the naked mole-rat. When the cells of the blind mole-rat grow to a certain density, these cells secrete large amounts of β-interferon, triggering widespread cell death and ultimately controlling the problem of excessively rapid cell proliferation. Besides naked mole-rats and blind mole-rats, bats are also a group of animals with anti-cancer capabilities. Scientists have conducted extensive investigations into tumor development in bats, but only a handful of tumors have been found, including leiomyosarcoma and pulmonary sarcoma. Recently, a large international collaborative research project conducted long-term, extensive, and comprehensive pathological studies on bats in Asia, Africa, and Australia, ultimately finding no individual bats with cancer. These studies suggest that bats, like other long-lived mammals (such as naked mole-rats and blind mole-rats), likely possess some unique and previously unknown anti-cancer mechanisms. Recent research indicates that the gene ABCB1, which encodes a transporter, is highly expressed in bats, significantly inhibiting DNA damage in bat cells. DNA damage is one of the main factors accelerating cell carcinogenesis, which may explain the low tumor incidence in bats. As the examples above show, while these wild animals all possess the ability to resist tumor development, the underlying molecular mechanisms differ. It is particularly noteworthy that bats have unique and unparalleled advantages compared to other cancer-fighting animals. First, bats are incredibly diverse, with over 1400 species identified so far, accounting for more than 25% of all mammal species, making them the second largest order of mammals after rodents. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that different bat species possess different anti-cancer mechanisms. Second, bats have a wide distribution and relatively large populations, making it easier to obtain research samples compared to other cancer-fighting animals. Finally, research on the anti-cancer mechanisms of bats is currently only the tip of the iceberg, with vast potential for further research. Therefore, protecting bats and conducting in-depth research on them may open new avenues for deepening and expanding our understanding of carcinogenesis mechanisms, thereby helping us develop drugs and tools to cure or inhibit cancer.

Bats have an extremely low probability of developing cancer (Image from the internet).

4. Bats have a powerful immune system that can offer insights into human health.

Innate immunity is the first line of defense against pathogens in organisms, consisting of a series of important responses to combat infection and maintain homeostasis. The innate immune system has evolved rapidly in vertebrates, believed to be a result of interactions between pathogens and hosts. Currently, many deadly viruses have been found in bats, such as SARS virus, Ebola virus, and Nipah virus. These viruses often cause severe systemic illness and even death in humans and other mammals. Surprisingly, unlike other mammals, bats carrying these viruses do not exhibit obvious clinical symptoms.

Studies have shown that the components of the bat's innate immune system are the same as those of other mammals, including interferon, interferon-activating genes, and natural killer cells. While the components are similar, their responses to deadly viruses differ, suggesting that the bat's innate immune system may possess unique molecular functions and regulatory expressions. Indeed, some components of the bat's innate immune system are more active than those of other mammals, indicating that bats may possess a 'always-ready' antiviral strategy. In other words, the bat's immune system is always on alert, effectively suppressing viral replication during the 'gap' between viral entry and detection and response. On the other hand, many molecules related to excessive immunity and inflammatory responses in bats are suppressed in both expression and function, preventing damage to tissues and organs during antiviral activity. Therefore, bats achieve coexistence with viruses through active innate immunity and suppressed inflammatory responses. These unique antiviral capabilities make the study of the bat's immune system particularly important, as such research can help humans better understand the occurrence and control of diseases, explore new methods of combating viruses, and ultimately develop new treatments.

Bats have a powerful immune system (image from the internet).

5. Bats possess superb flying skills, which have inspired the development of aircraft.

Bats are the only mammals with true flight capabilities, possessing remarkable aerodynamic abilities. Scientists, through in-depth research into the aerodynamic principles of bat flight, have discovered that the flapping of their wings, along with their flexibility and elasticity, are perfectly coordinated during flight. Bat flight is arguably the most wondrous and perfect form of movement in the world, unmatched by birds or insects. Utilizing these flight principles, scientists have developed bat-like robots, which will be responsible for performing many extreme flight tasks (such as those in confined spaces) in the future.

Furthermore, bats are of great significance to the development of next-generation aircraft (including drones) because they are naturally adapted to flying in high-density and complex environments. To ensure the safety of our aircraft, we heavily rely on the cooperation of ground-based air traffic control systems. In civil aviation, we require each flight to take off independently, fly along pre-planned routes, and land on specific flight paths. Even with such stringent monitoring, we still hear news of plane crashes from time to time. At the other extreme, bats not only do not require pre-planned routes, but also any external guidance, perfectly embodying the concept of safe flight. Even more remarkable is the ability of hundreds or even thousands of bats (or more) to fly safely simultaneously in confined spaces in certain extreme environments. If one day in the future, bats' flight techniques are fully understood and applied to modern aircraft, then achieving "intelligent flight" and "safe flight" will truly be a reality.

A bat-shaped robot designed to mimic the flight of a flying fox (image from the internet).

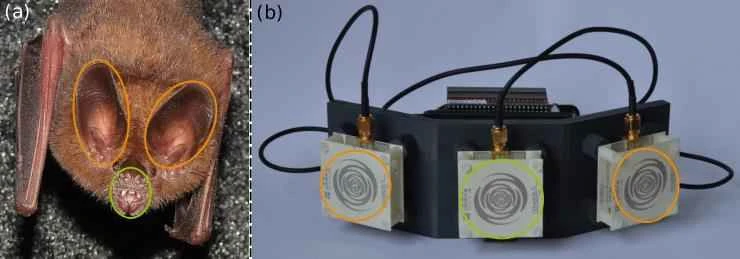

6. Bats' unique echolocation ability has inspired scientists to develop new radar systems.

Although radar was invented before the discovery of bat echolocation, later improvements to radar systems were inspired by bat echolocation. For example, bats emit ultrasonic waves to locate obstacles and prey during flight, but background noise overlaps and interferes with their echoes. A similar problem arises when bats chase moths through dense foliage, as signals bounced off leaves and create interference. However, bats overcome this problem by recording a "mental fingerprint" of each sound and its corresponding echo in their memory. This allows them to separate signals by slightly altering the frequency, thus creating a mismatch between one signal and another. This ability of bats can help scientists learn new methods for developing radar and sonar equipment, thereby avoiding electromechanical interference with radar systems.

Perhaps what we need to remember is that human radar development has a history of less than a century, while echolocation, a technology with a similar principle to radar, has been improved and used by bats under the pressure of natural selection for approximately 65 million years. While we rack our brains trying to improve the detection range and tracking accuracy of our own radar, we also struggle with how to prevent our equipment from being detected by the enemy's radar systems. This military equipment race has continued since the development of radar. Interestingly, this military equipment race bears a striking resemblance to the "predator-prey" equipment race between bats and their prey: as hunters, bats, under the pressure of natural selection, constantly improve the performance of their echolocation systems; insects, as prey, similarly, under the pressure of natural selection, constantly enhance their anti-predator skills. This may also explain why the US military funds bat biological research every year.

Bats and radar sensors (Image from the internet)

7. Bats are mammalian models for understanding the brain mechanisms of human language.

Language is one of the defining characteristics of humankind, playing a crucial role in driving human evolution and the development of social civilization. However, how did language evolve? What are the brain mechanisms controlling and learning language? These fundamental questions remain unclear. For many years, songbirds have been the primary animal model for language research, but there has been a lack of mammalian models more closely related to humans. Recent research suggests that bats may become one of the promising mammalian models for scientists to study brain mechanisms.

It is well known that human language is learned, an ability known as vocalization. However, vocalization is extremely rare among mammals. Currently, only a few mammals, such as bats, elephants, and dolphins, have been confirmed to possess this ability. Clearly, due to limitations in size, species diversity, and population size, bats are more ideal experimental animals than elephants and dolphins. Bats have high species diversity, with many species living in highly gregarious societies and possessing complex social structures; this high degree of sociality is a key factor in the evolution of language. Furthermore, unlike most mammals, echolocation bats exhibit extremely high vocal activity (ranging from a few to hundreds of vocalizations per second), providing a convenient behavioral model for studying the brain mechanisms of vocal control. Perhaps due to the unique advantages bats possess in studying sound communication and navigation, research on bat vocal control and learning is one of the main model species for animal sound communication research, and it holds promise for unlocking the brain mechanisms of human language.

Bat vocalization control and learning (Image courtesy of Luo Jinhong)

8. Bats help unravel the secrets of spatial perception and navigation in the human and animal brains.

When we leave our homes and stroll through a nearby park or shopping mall, we can always easily find our way home. In this familiar process, our brains provide a wealth of incredibly precise navigational information. For example, how far to walk from the mall entrance to the next intersection, and then turn left or right. So, how does our brain know this location, distance, and direction information? To address these questions, Professor O'Keefe and his postdoctoral students, the Moser couple, and other scientists in the UK have done a series of outstanding works. They discovered navigation cells in the hippocampus and its adjacent entorhinal cortex of the rat brain—"place cells" that process location information, "grid cells" that process distance information, and "head-facing cells" that process direction information—forming a kind of "GPS" in the brain. Professor O'Keefe and the Moser couple shared the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for this discovery. However, these findings were obtained in two-dimensional (2D) space. What about in a more realistic 3D environment? In this case, conventional animal models such as mice or rats can no longer be used as experimental subjects. Scientists considered bats, the only mammals capable of flight that live in 3D space, and have conducted extensive and outstanding research using bats as experimental subjects. Their findings reveal that in 3D space, position cells in the bat hippocampus exhibit isotropic processing of vertical and horizontal information; cells in the anterior hippocampus can continuously characterize the three Euler angles (horizontal azimuth, pitch, and roll) of the head orientation, enabling precise acquisition of directional information in 3D space.

When moving from one environment to another, our brain's "GPS" needs to reset to adapt to the navigation requirements of the new environment. A crucial scientific question is: how often does our brain's "GPS" reset? Previous studies suggested this timescale was around one minute. However, utilizing the high temporal accuracy of echolocation in bats, researchers discovered that the "GPS" reset time is around 300 milliseconds, significantly exceeding previous understanding. Some bat species possess both visual and echolocation abilities. Researchers used this characteristic to compare the ability of place cells to process location information under visual and auditory cues. The results showed that place cells have higher spatial resolution under visual cues. Furthermore, the study also discovered "social place cells" in the bat hippocampus that recognize the locations of other bats. Although the mechanisms of brain navigation are becoming clearer, many questions about spatial navigation remain unanswered. For example, how do the brain regions containing these navigation cells cooperate to complete navigation tasks? Current research is conducted in laboratory environments with extremely limited space; how does navigation differ in real natural environments on a large spatial scale? And so on. It's easy to imagine that by utilizing the fascinating, species-specific characteristics of bats, the secrets of brain navigation in 3D space will continue to be unlocked!

Bats' three-dimensional spatial navigation (Image from the internet)

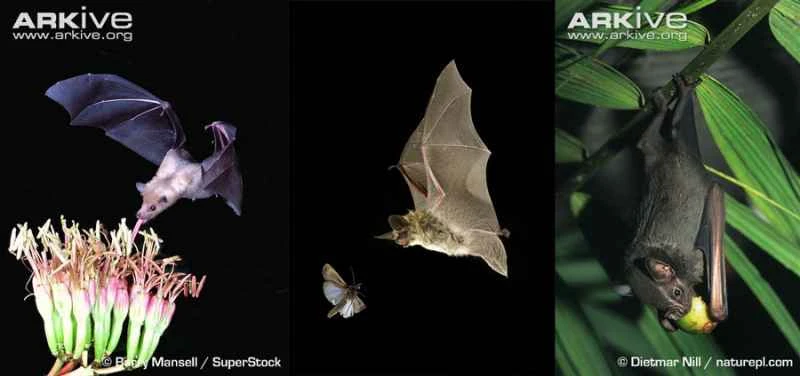

8. Bats are an indispensable group of animals for maintaining a healthy ecosystem.

Bats have long played a crucial role in pest control, seed dispersal, plant pollination, and forest succession. Although different bat species exhibit diverse diets, including insectivorous, fruit-eating, nectar-eating, fish-eating, carnivorous, and even blood-eating, over two-thirds of bats are obligate or facultative insectivores. In their ecosystems, bats are the primary controllers of nocturnal insects, consuming large quantities each night. It is estimated that captive bats consume about a quarter of their body weight in insects daily; however, under wild conditions and during high-energy-consuming periods such as lactation, this figure can reach as high as 70%, and sometimes even exceed 100%.

Bats frequently inhabit farmland, often ambushing and preying on numerous potential agricultural pests. Studies have shown that the Brazilian dog-nosed bat ( Tadarida brasiliensis ) preys on a variety of agriculturally relevant pests. Furthermore, because many major agricultural pests are migratory, the value bats bring to agriculture can extend to other agricultural areas hundreds of kilometers away, not just limited to their local foraging areas. Research indicates that bats are exceptionally adept at predation in farmland. A study by Cleveland et al. assessed the economic value of pest control services provided by the Brazilian dog-nosed bat to cotton production in south-central Texas, finding that bats prevent cotton damage and pesticide use by preying on pests annually, representing 15% of the final cotton yield value. In North America alone, the value of bats reducing crop damage and avoiding pesticide use is approximately $22.9 billion per year. In Thailand, bats prevent nearly 2,900 tons of rice loss annually by preying on pests in rice paddies, generating an economic value exceeding $1.2 million, meaning that bats in Thailand could provide food for nearly 30,000 people each year. Furthermore, researchers, through large-scale fencing experiments in cornfields, discovered that bats exert sufficient pressure on crop pests to suppress larval density and damage, while simultaneously reducing the growth of pest-related fungi and fungal toxins in corn. It is conservatively estimated that globally, the value generated by insectivorous bats through pest control in corn cultivation alone exceeds $1 billion. Bats can further benefit humanity by indirectly suppressing pest-related fungal growth and toxic compounds in corn. In many cases, the larvae of numerous agricultural pests can damage crops, while bats prey on the adult pests, preventing them from laying eggs and thus reducing larval development. Therefore, bat predation on pests may have a cascading effect on the agricultural ecosystem.

Traditional methods for studying bat diets involve morphological analysis of food residues in bat feces; however, this method has significant limitations and hinders research on bat diets. With the development of modern molecular biology techniques, such as DNA metabarcoding and environmental DNA (e-DNA) analysis, we have gained new insights into the ecological services provided by bats in preying on pests. Aizpurua et al. (2018) used e-DNA analysis to study the diet of the common long-winged bat ( Minipterus schreibersii ) across Europe, finding that it preys on over 200 arthropod species, including 44 agricultural pests that can damage many crops across the continent. Furthermore, the common long-winged bat can adjust its diet according to available food resources in local farmland, reshaping its ecological niche. This suggests that the suppressive role of bats in agricultural pests has long been severely underestimated.

Furthermore, bats provide crucial ecosystem services by pollinating and dispersing a wide variety of plant seeds. Studies on durian pollination ecology show that while the honeybee ( Apis dorsata ) is the most frequent visitor to durian flowers, fruit bats, especially the long-tongued fruit bat ( Eonycteris spelaea ), are the primary pollinators, visiting the flowers an average of 26 times per night. In tropical regions, flying foxes, due to their large size and high mobility, are highly efficient pollinators and seed dispersers, with many flying foxes flying distances exceeding 60 kilometers per night from their roosts to their foraging grounds. Bats shape the diversity and physical structure of forest communities, enabling the survival of many plants and animals within them. In nature, many plants rely on bats for reproduction to varying degrees, including many economic crops such as bananas, mangoes, and guavas. On islands, evolutionary chance and the extinction of other local seed dispersers due to human activity mean that flying foxes have become the sole pollinator or seed disperser. Therefore, flying foxes are key species endemic to their local or island habitats, crucial for maintaining plant viability. The extinction of flying foxes on the island could trigger a chain reaction of extinctions, leading to irreversible ecological and economic consequences.

Bats' ecosystem services: pollination, pest control, and seed dispersal (Image from the internet)

10. Bat populations have declined drastically and urgently need protection.

Bats comprise over 1,400 species globally, boasting exceptional biodiversity and ranking among the world's most widely distributed, numerous, and evolutionarily successful mammal groups. Except for polar regions and some islands in the oceans, they utilize a vast array of terrestrial ecosystems across the Earth, providing a range of vital ecosystem services. However, existing bat populations face multiple threats, and their survival is precarious. In recent years, increasing human activities have led to unprecedented declines or extinctions in bat populations, including the depletion or destruction of forests and other terrestrial ecosystems, human disturbance of caves, habitat loss, hunting, white-nose syndrome, pesticide overuse, and the increasing use of wind power equipment. According to our field survey data from the past 20 years, the bat population in China has declined by more than 50% compared to 2000, with cave tourism development, pesticide overuse, and indiscriminate hunting being the three main causes. The mass mortality of bats not only threatens biodiversity but also has severe economic consequences. Studies indicate that in North America alone, bat deaths caused by factors such as white-nose syndrome and wind power generation could result in agricultural losses estimated at over $3.7 billion per year. Because bats have long generation cycles and low reproductive rates, their populations recover extremely slowly once damaged. However, in China, not only are public misunderstandings about bats stemming from the spread of certain diseases, but the lack of research on bats' functions within ecosystems has also prevented the government and the public from paying sufficient attention. The current state of bat biodiversity conservation in China is particularly worrying; to date, no bat species is listed in the "National Key Protected Wild Animals List of China." Protecting bat populations and habitats from destruction is not only crucial for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem function, but also a vital guarantee for ecosystem integrity, national economy, and human well-being.

In fact, the primary reason bats transmit zoonotic diseases is human interference. Deforestation reduces bats' natural habitats, forcing them out of their original ecological niches. These bats lose their usual foraging and behavioral patterns, encroaching on areas near human settlements, and directly or indirectly transmitting viruses to humans or livestock. If bats forage in areas inhabited by humans, the chances of cross-species transmission of viruses within them increase. If local residents consume bats as wild game, disease will be the bats' best defense mechanism. We urge that as long as humans do not disturb bats, destroy their habitats, or consume bats and their food, viruses carried by bats may not infect humans. On the contrary, bats will bring benefits to the health of the ecosystem, human health, and longevity. As recorded in the Book of Documents, bats bring "five blessings": longevity, wealth, health and peace, virtue, and a peaceful death.

Bat populations have declined drastically and urgently need protection. (Image from the internet)

author:

Professor Zhao Huabin of Wuhan University

Professor Luo Jinhong of Central China Normal University

Associate Professor Fu Ziying, Central China Normal University

Researcher Liu Zhen, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Jiang Tinglei, Associate Professor, Northeast Normal University

Mao Xiuguang, Associate Research Fellow, East China Normal University

Zhou Peng, researcher at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Researcher Zhang Libiao, Guangdong Institute of Applied Biological Resources