As humanity has developed, natural selection has played a crucial role in human evolution, rendering many once-useful bodily functions or organs redundant. Surprisingly, many organs have been preserved in some form, allowing us to observe the evolutionary process of humankind.

1. Goosebumps

People get goosebumps when they feel cold, scared, angry, or filled with awe. Many animals get goosebumps for the same reason; for example, cats and dogs raise their fur, and porcupines stand on end. In cold environments, raised fur insulates against cold air, preventing it from directly contacting the skin and providing warmth. When afraid, goosebumps make animals appear larger, hoping to scare away predators. Humans no longer benefit from goosebumps; they are merely a legacy from ancient times when we had no clothes and needed to scare away predators. Natural selection shed thick fur, but left behind the underlying control mechanisms.

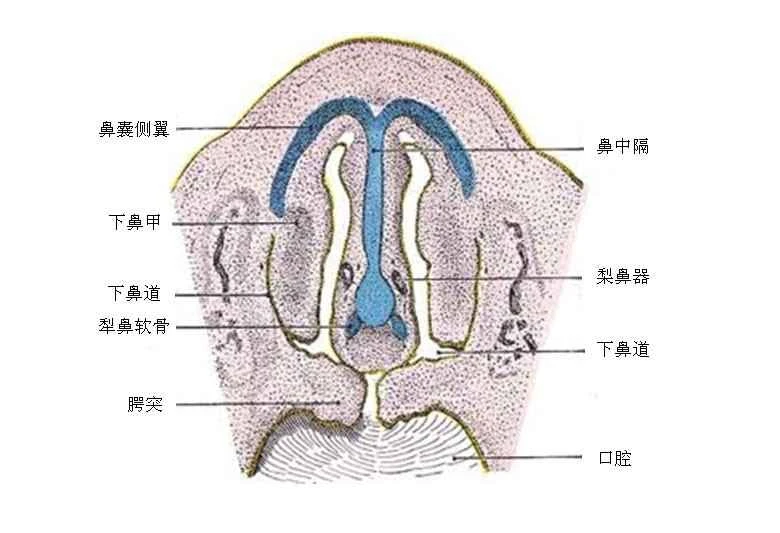

2. Piriformis apparatus – a tool for tracking the opposite sex

The villiform organ is a fascinating anatomical organ that tells the story of human sexual development. Located inside the nose, this specialized "olfactory" organ detects pheromones (chemical substances that trigger sexual desire, alertness, or food cues). It is this organ that helps some animals track mates and detect potential danger. Humans are born with a villiform organ, but in early development, its function degenerated to the point of being almost nonexistent. Long ago, when communication was limited, humans might have used this organ to find mates. Today, however, singles nights, chat rooms, and bars have replaced its role in human courtship.

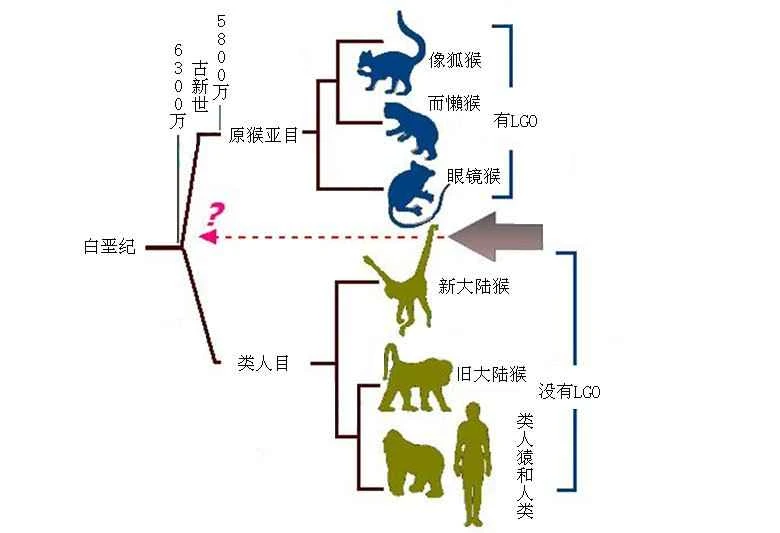

3. Waste DNA – L-gulonolactone oxidase (LGO)

While most remnants of human evolutionary history are visible, some are not. In human genes, there is a structure that was once used to secrete a digestive enzyme (L-gulonolactone oxidase) that helps metabolize vitamin C. Most other animals possess this useful DNA, but a change in our evolutionary history rendered this gene ineffective—though a small remnant remained, becoming "waste DNA." This waste DNA demonstrates that we share a common ancestor with other species on Earth, giving this "waste" a special significance.

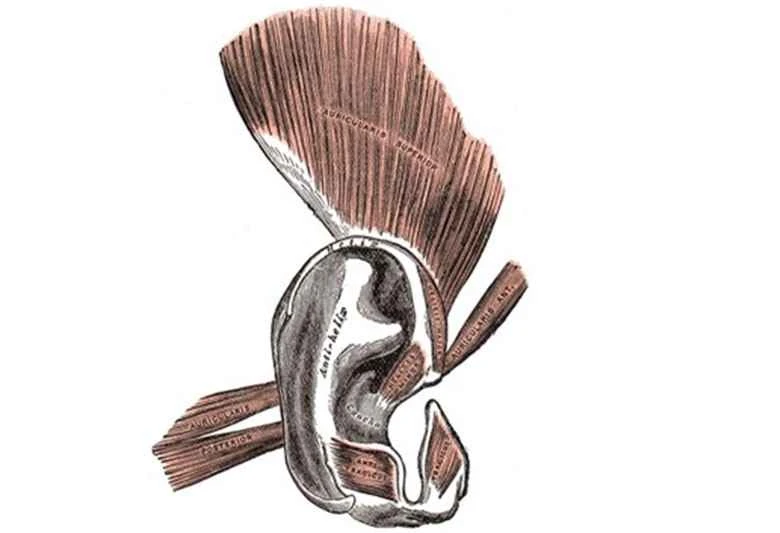

4. External ear muscles

Sometimes you might be surprised to find that some people can twitch their ears like animals. This interesting phenomenon is also a legacy of human evolution—the function of the extraauricular muscles. The extraauricular muscles are a group of muscles at the ear canal point, which animals use to rotate and control their ears (independent of their heads) to focus attention on specific sounds. Humans still retain this group of muscles that once served the same function, but these muscles have become very weak, and can only twitch their ears slightly at most. The function of these muscles is very evident in cats (they can even rotate their ears 180 degrees), especially when they are tracking small birds, where the movements must be as small as possible so as not to scare away their potential lunch.

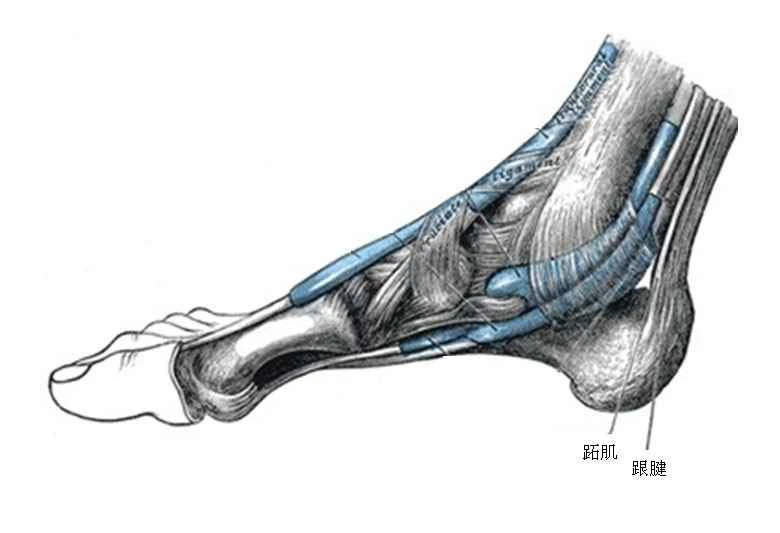

5. Plantar muscles (zhíji)

In animals, the plantar muscles are used to grasp and control objects on the feet; you can see this in chimpanzees, whose feet are as dexterous as their hands. Humans also have this muscle, but it's so underdeveloped that doctors often remove it during muscle reconstruction. In fact, this muscle is practically useless; 9% of people are born without it.

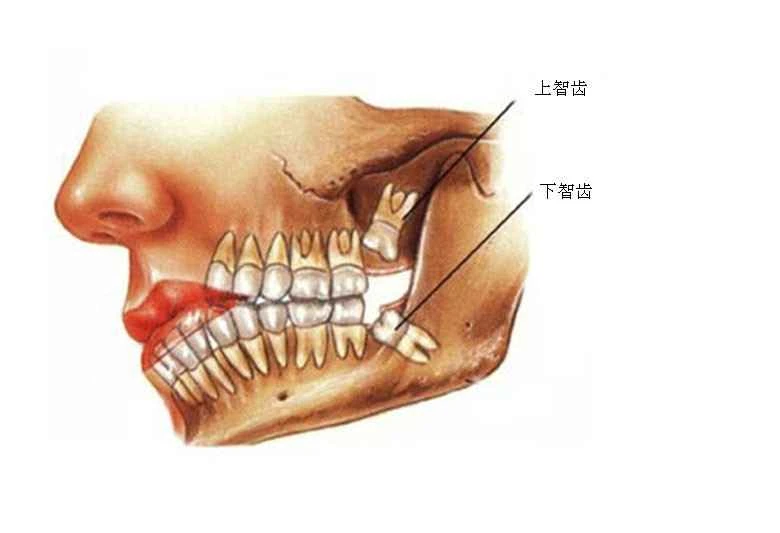

6. Wisdom teeth

Early humans consumed a lot of plants, and they needed to eat quickly to ensure they had enough nutrients each day. For this reason, we developed an extra set of molars, making our mouths larger and more efficient. This function was especially important because we couldn't efficiently digest cellulose. Due to continuous selection during evolution, our diet changed, and our jaws became smaller, rendering the third molars unnecessary. Some populations no longer grow wisdom teeth at all, while in others, almost 100% of people grow them.

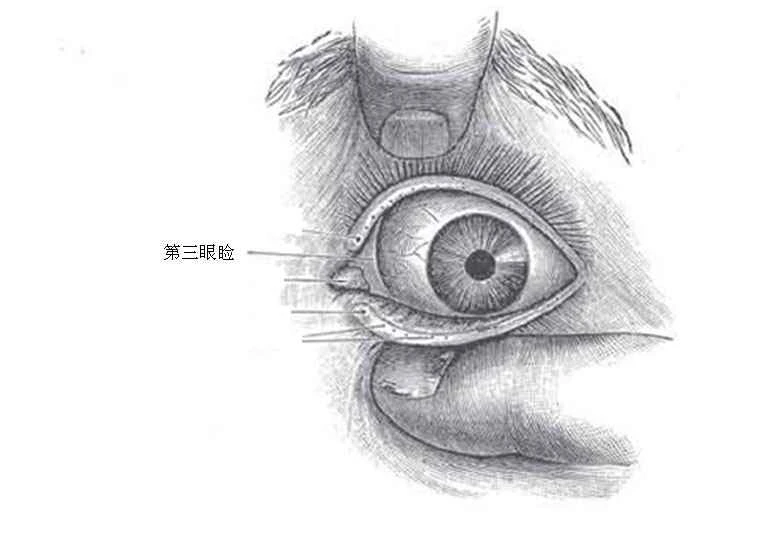

7. Third eyelid

When a cat blinks, if you look closely, you'll see a white film over its eye; this is called the third eyelid. This is unusual in mammals, but quite common in birds, reptiles, and fish. Humans also retain traces of a third eyelid. The human third eyelid is quite small, but it's more prominent in some species. Only one primate species has retained the function of a third eyelid: the golden bear macaque (closely related to lemurs) living in West Africa.

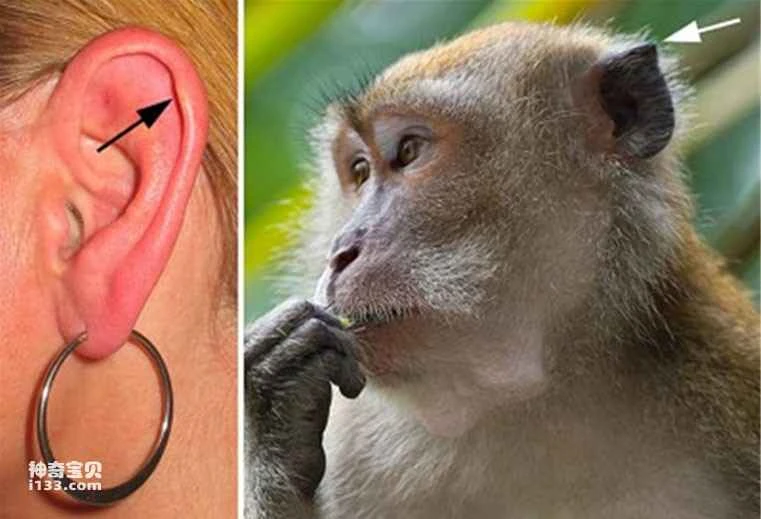

8. Crescent folds

The semilunar fold is a small, elongated growth located at the junction of the upper and middle parts of the ear, present in many mammals, including humans. Its function was likely to help animals hear, but it serves no purpose in humans. This historical human legacy is still visible in only 0.4% of people, but many more likely carry the gene, as it is not always expressed through bending of the earlobe.

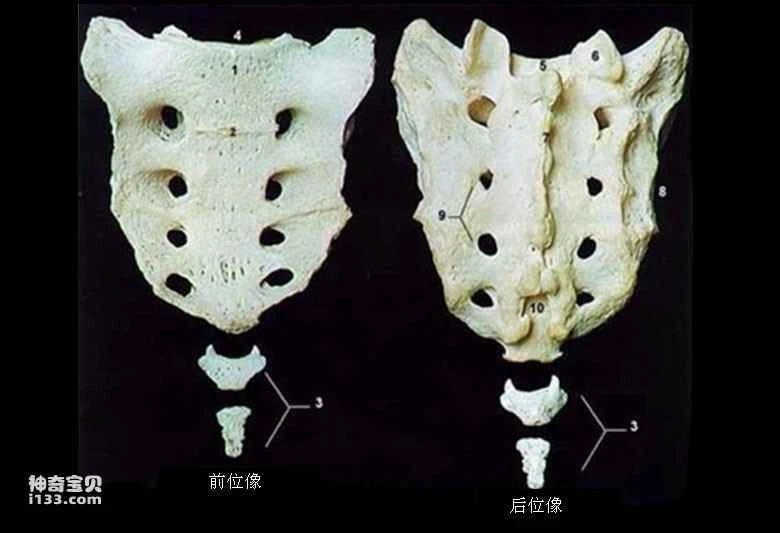

9. Coccyx

The coccyx is a remnant of the long tail we once had. We've gradually stopped needing tails (Neanderthals stopped swinging in trees and started rolling on the ground), but the coccyx still has some use: it now supports many muscles and provides support when sitting or bending over. In addition, the coccyx also supports the anus.

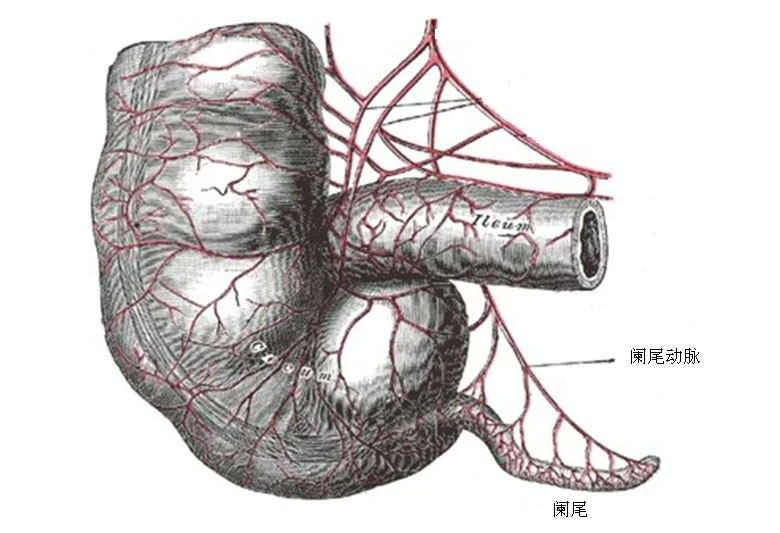

10. Appendix

For modern humans, the appendix has no known function and is frequently removed when infected. While its original function remains uncertain, most scientists agree with Darwin that it originally helped us digest the cellulose in our leafy diet. During evolution, as our diet changed, the appendix became increasingly useless. Interestingly, many evolutionary theorists believe that natural selection (while eliminating all functions of the appendix) favored larger appendices because they are less prone to inflammation or disease. Therefore, unlike the little finger, which may eventually atrophy and become equally useless, the appendix may very well remain for a long time—lounging around, doing absolutely nothing!