The tortoise has always held a unique and highly revered position in Chinese culture. It is grouped with the dragon, phoenix, and qilin as the Four Auspicious Beasts. The tortoise is seen as a symbol of longevity, as mentioned in Cao Cao's poem "Though the Tortoise Lives Long." The tortoise is also considered a medium between humans and gods; during the Shang Dynasty, shamans burned tortoise shells to predict good and bad fortune, then inscribed the divination results on the shells, leaving behind early Chinese characters—oracle bone script. Today, tortoises are primarily kept as pets, food, and are endangered protected animals. While tortoises are familiar to the public, how many people have actually observed their anatomy closely?

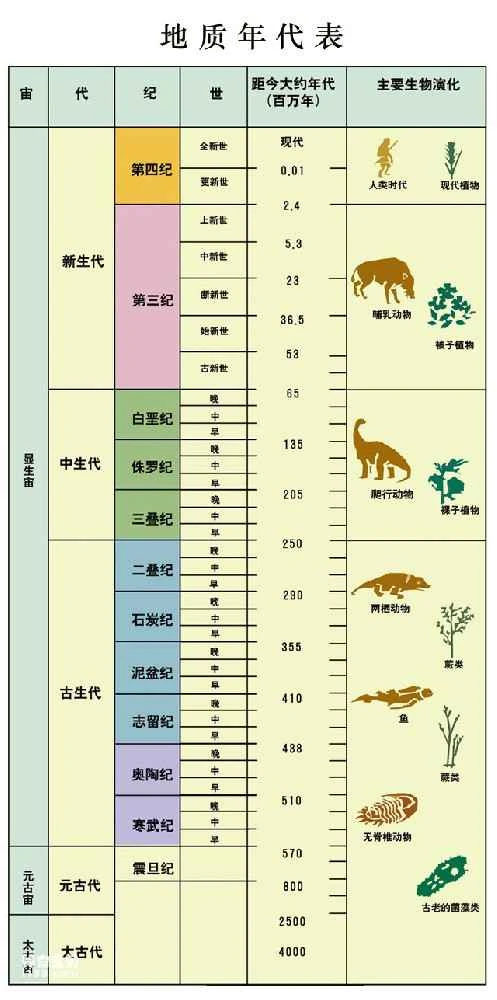

To defend against attacks, tetrapods have armor covering their bodies—among mammals, there are living armadillos and extinct glyptodonts; among dinosaurs, there are ankylosaurs; and among marine reptiles, there are placoderms. But the animal with the most complete armor is undoubtedly the turtle. While the bony plates covering the bodies of other animals originate from the skin, the turtle's shell originates from multiple parts of its skeleton and is closely connected to its internal structure. The turtle shell is divided into two parts: the carapace (back) and the plastron (ventral). Except for secondary degeneration, they generally consist of two layers: the outer layer is keratinous, composed of many scutes; the inner layer is bony, composed of many bony plates. Its carapace is fused with the spine and ribs, which are located outside the shoulder and pelvic girdle. This allows it to retract its head, limbs, and tail into its shell. Besides its unique shell, the turtle's skull is also unique. In amniotes, the arrangement of the four bones—postorbital, squamous, yoke, and parietal—is the primary basis for classification, and there are three basic types: if these four bones are a single, continuous structure without a perforation, it is the non-perforated type; if there is a temporal foramen between the postorbital, squamous, and yoke bones, it is the inferior foramen type; and if there are two foramina, it is the double foramen type. The temporal region of the skull of modern turtles is open, but they lack a temporal arch, which differs from the typical types.

Comparison of the skull of the turtle with three types of early amniotic skulls: A. imperforate skull; B. inferior foramen skull; C. double foramen skull (abbreviations: L, inferior temporal foramen; Or, orbit; P, parietal bone; Po, postorbital bone; S, superior temporal foramen; Sq, squamous bone).

Protojas fossil, top right view of the skull top view

How did the turtle's unique head and body structure come about? This involves two questions. First, what were the turtle's ancestors like? This is the question of origin. Second, how did the turtle evolve step by step from its ancestors (whose structure was not much different from that of other tetrapods)? These two questions can only be answered by fossils. More than a hundred years ago, a turtle from more than 200 million years ago (Late Triassic) was discovered in Germany: *Proganochelys*. It was easy to classify it as a turtle because it already had a complete carapace and plastron; however, its skull had a complete temporal region, so turtles were long classified as anapsids. This was the mainstream view for more than a hundred years, and paleontologists generally looked for the turtle's ancestors within the anapsids. In 1914, Watson summarized the common characteristics of turtles, proposed the morphology that its ancestors should have, and then specifically pointed out that the *Eunotosaurus* (formerly translated as the Southern Turtle), with eight pairs of specialized ribs, was likely the ancestor of turtles. In 1946, Gregory compared turtles to early reptiles, suggesting they originated from cuposaurs (including serpentinosaurs, plesiosaurs, and simian salamanders), with serpentinosaurs being more closely related than broad-toothed saurids. Olson, in 1947, proposed that turtles originated from broad-toothed saurids. Many previously accepted the view that turtles were more closely related to the common lizard, such as Romer, who classified the common lizard in his classic *Skeletoneography of Reptilia*. With the rise of phylogenetics, many analyses have supported the idea that turtles are parareptiles, more closely related to serpentinosaurs or plesiosaurs; some have even proposed that turtles are most closely related to megalodontids. However, neither the serpentinosaur nor the plesiosaur theory can explain the origin of the turtle's unique shell, making it difficult to accept.

Southern lizard skull (top) and postcranial skeleton (bottom)

Some scholars believe that turtles should belong to the Diapsids. Goodrich (1916) believed that reptiles are divided into two branches: one called Sauropsida (including birds) and the other Theropsida (including mammals). Turtles were classified as the former because of the hook-shaped fifth metatarsal and the structure of their hearts. He believed that the skull of turtles was inconsistent with that of true anapsids. Some zoologists believe that turtles are Diapsids based on the adductor muscles of the jaw, while de Beer (1937) and others further believe that turtles are more closely related to archosaurs (crocodiles, birds, and fossil relatives) based on the development of the lateral vertebral bodies of the anterior atlantovertebra and features such as the secondary subclavian artery. Rieppel carefully analyzed many morphological features of extant organisms (many of which are soft-bodied features) and believed that most of them were not valid. de Braga and Rieppel (1997), in analyzing the relationships of amniotes, found that turtles are closely related to the Mesozoic marine reptiles, the plesiosaurs, which are at the base of the plesiosauroid branch (cubitosaurs, lizards, and fossil relatives). This aligns with the classification of turtles into the Diptera group in extant biological research, particularly molecular biology. However, the latter supports the view that turtles are more closely related to crocodiles and birds than to lizards. Werneburg and Sanchez-Villagre (2009), based on their analysis of the developmental sequence of morphology during embryonic development, believe that turtles occupy a basal position among extant reptiles.

The origin of turtles also involves an environmental question: were the earliest turtles aquatic or terrestrial? Triassic turtle fossils have been found in Argentina, Germany, and Thailand, all in terrestrial strata. Furthermore, studies of the forelimbs, shell morphology, and shell histology of complete fossils of *Protojac* and *Palaeochersis* support the view that these two early turtles were terrestrial, thus supporting the terrestrial origin theory of turtles. Rieppel and Reisz (1999), based on the turtle's respiratory and locomotion methods and plastron, proposed that turtles originated aquaticly.

Regardless of which group turtles are more closely related to, the origin of their unique morphology must be explained. Cuvier (1799, 1812) was the first to propose that the middle part of the turtle shell, namely the vertebral plates and costal plates, is formed by the widening of the dorsal vertebral arches and the widening of the dorsal ribs, forming sutures. Irwin et al., however, believed that the turtle shell originated from dermal ossification, which fused with the axial skeleton. These earliest debates were based on embryological studies, and later, the inclusion of leatherback turtles as a primitive stage in shell evolution and the misidentification of placodonts as turtles further solidified researchers' adherence to the dermal ossification theory. After more than a century of developmental research, this question remains unanswered. Some believe that the vertebral plates and costal plates seem to have been formed by a mixture of the endoskeleton and osteoderm during development. Furthermore, the results of studies on different groups seem to differ. Gilbert, in his research on red-eared sliders and alligator snapping turtles, proposed that the shell evolved from the epidermis, while Kuratani's team, in their 2013 research on soft-shelled turtles, found that the shell originated from the internal skeleton, rather than from the epidermis or exoskeleton.

This controversy is also related to reconstructing the ancestor of turtles. If the origin of the turtle shell is related to dermal bone, then the ancestor of turtles should be sought within this group. *Protochelys* has a complete shell and dermal bone, which does not help solve this problem. In 2008, Li Chun and other scholars discovered several fossils in the limestone of Guanling, Guizhou. After repairing them, they were found to be turtles, but without a complete carapace and possessing teeth, and were named *Hymenochelys*. It had a complete plastron, while the carapace only had nerve plates, and the dorsal ribs were widened, but without dermal bone. This is consistent with the embryonic development stage of modern softshell turtles, and the shell was not formed by the fusion of dermal bone and skin. This fossil lived in the edge of the ocean or a delta, possibly indicating that turtles originated in the water. This fossil pushes the appearance of turtles back to about 220 million years ago, but its skull is poorly preserved and also imperforate, providing no new information in this regard. However, some scientists question whether the incomplete shell of *Hymenochelys* was a degeneration of adaptation to aquatic life. The recent discovery of new turtle fossils in Guanling may provide some new explanations.

The discovery of *Pappochelys* led paleontologists to shift their focus from the idea that turtle shell formation was related to dermal bone to that of *Pappochelys*, which lived approximately 260 million years ago. Lyson and Bever, among others, pointed out that *Pappochelys* shared some unique features with turtles in its postcranial skeleton, such as nine elongated trunk vertebrae, nine pairs of widened T-shaped ribs, and the absence of intercostal muscles. Their initial analysis in 2013 still classified turtles as parareptilia. Later, detailed analysis of the *Pappochelys* skull supported a close kinship between turtles and *Pappochelys*; it was also discovered that juvenile *Pappochelys* possessed both superior and inferior temporal fenestrae, which were covered by the remaining bones in adults. The final results supported the conclusion that both *Pappochelys* and turtles were diapsids, and the paper was published in *Nature* in 2015. Recently, some specimens discovered in Germany, named *Pappochelys*, dating back 240 million years, are considered to be intermediate in age and structure between *Pappochelys* and *Pappochelys*. It still retains the superior temporal foramen and the open inferior temporal foramen, suggesting that the plastron may have been formed by the aggregation of peritoneal ribs. This fossil is abundant in lacustrine sediments, indicating that it lived near water or frequently entered the water.

Current research tends to classify turtles as belonging to the Diptera. However, their specific position within Diptera remains unresolved: is it a branch of archosaurs, a branch of lepidosaurs, or a more basal position outside both? In Bever et al.'s 2015 results, parsimony supports a lepidosaur branch, while Bayesian methods suggest a position outside the Diptera crown group. Previous molecular biology studies have supported a closer relationship to archosaurs (crocodiles, birds), but if genes are considered as traits, several possibilities emerge. More fossils and more comprehensive, in-depth research are needed to resolve these questions.